Throughout much of my career as an architect and urban planner, I was involved in many endeavors that fall into the category of “microeconomics.” That is, they were policies, programs, or projects that benefitted a community through improvements in infrastructure or public buildings. Examples would be a civic center, a transit station, street enhancements, or creating a package of incentives to encourage private investment. I was fortunate to be able to draw strategies from a cadre of colleagues, some educated and experienced in microeconomics, with whom I worked.

Occasionally I would encounter people working on the larger scale of macroeconomics. They addressed issues at a state or national scale, with tools such as taxation, interest rates, money markets, financing, etc. It was an entirely different world, with terminology and techniques unfamiliar to me.

Recently I discovered a third type of economics that I had never come across before: “nanoeconomics.” This is a system of economics centered around small transactions between individuals — often by people who know each other. This we have discovered since moving to Italy six years ago. We rarely experienced it when we were merely visiting.

Sometimes the transaction is monetary, sometimes it comes in other forms. Its origins are ancient, dating back to time before physical currencies. It sometimes goes by the name “bartering.” However, that suggests a deliberate reckoning of the value of an exchange of goods or services. I’m talking about a broader concept of trade, but not necessarily expecting a specific compensation — if any at all — in return.

As Americans, coming from a culture of rampant capitalism where monetary value is placed on almost every transaction, this economic model came as something of a shock. My wife and I often found ourselves bewildered and wondering if we needed to recompense a specific gesture with another comparable gesture. As recipients of many unexpected gestures from people in our village of Santa Vittoria in Matenano, in east-central Italy, we were confused. Was something reciprocal even expected? A cynic might view these gestures through a nefarious lens. Did these favors come with a Godfather-like payoff expected in the future? When that never happened, we were puzzled.

Perhaps a few examples would explain this cross-cultural conundrum.

Six months after moving to Italy in 2016, we purchased a used car, a small black Kia Picanto with 150,000 km on it. Although it was 12 years old, it served us well for day trips, longer trips, and monthly forays to IKEA — whether we needed anything or not. It had great fuel efficiency but minimal comfort. The vehicle also needed maintenance or repair work several times a year.

Consequently, we got to know the village mechanic well. A rough-hewn, muscular man of a certain age, Gabrielle has an auto repair shop on the ground floor of his house where he lives with his wife. Strewn outside the shop is an array of cars, trucks, and farm vehicles, some obviously cannibalized for parts. Or perhaps awaiting parts.

One day on a drive in the countryside, we got lost on a winding road we had never traveled on before. We had no idea where we were. Worse, the car suddenly ground to a dead halt. No amount of coaxing could get it started. We pushed it into a dirt lane leading to a famer’s house, asked his permission to leave the car there, and then called an Italian friend who somehow found us. Before leaving the car, we managed to lock the only keys we had for it inside, dangling from the ignition. It was not a good day.

The next morning, we called Gabrielle for help. He dropped everything, went out, found our car, somehow got into it, brought it back, and repaired it. Two days later he showed up at our door with the vehicle, fixed and good to drive. He asked for a surprisingly modest sum, which we gladly paid. And then he took us under his wing.

Flash forward to this summer. Passing by our garden Gabrielle noticed that none of our vegetable plants were doing well, mainly due to my erratic watering routine. They had also suffered through an unusually fierce heat wave in July. There were sad specimens of brown tomato vines and other vegetative disasters. The next day our mechanic brought us an enormous basket of vegetables and fruits, including a huge watermelon – all from his own thriving, garden. We were astounded. He was worried we might starve.

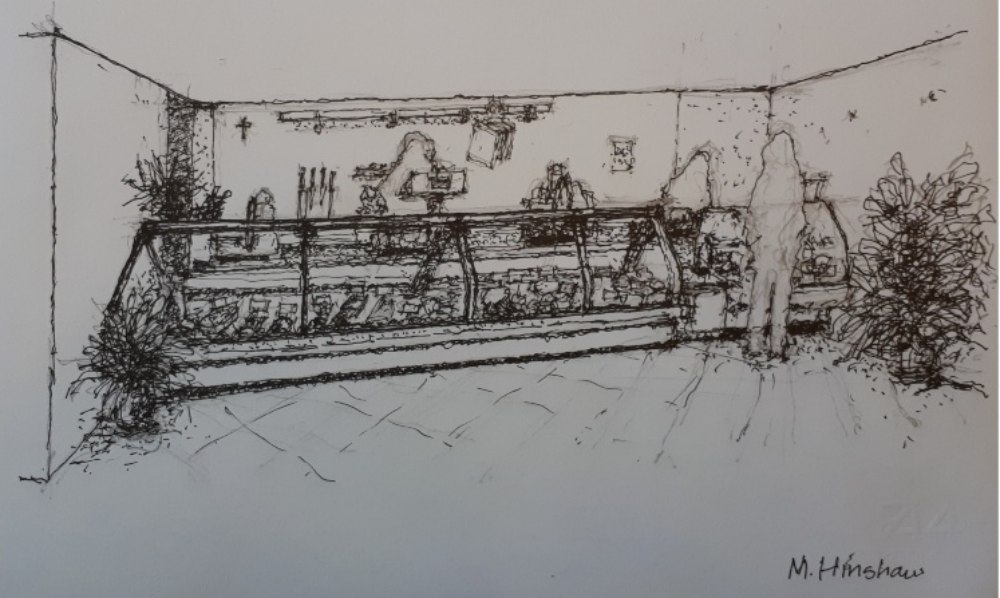

Another example. During the pandemic, when lockdowns were so strict you could not leave your own town, save for work, I found a way to keep myself occupied. Over the course of six months of spring and summer, I went out for walks with my sketchbook and a packet of pencils and pens. I sketched, in an impressionistic form, my take on shops, restaurants, cafes, and houses. Upon completion of each, I would make a good copy on stiff paper stock and present the drawing to the owner of the business or house.

Samuela, a restaurant owner was so delighted with the drawing that recently she showed me what she had done with it. Not only had she framed it and placed it by the cash counter, but she was now using it as part of her logo too. During the pandemic, we had ordered food to go frequently from her restaurant, as we wanted to ensure its survival as best we could. Just yesterday, Samuela dropped by our house, pushing her new baby in a pram, to give me a birthday gift. I was deeply touched.

Now, whenever we go to the restaurant for a meal, I see my drawing everywhere, as it is printed on the little paper packets that hold the tableware and napkin. I was flattered by this unexpected gesture. Since then, I discovered that each dinner check we get includes a significant reduction. But at no point did anyone discuss money. Nanoeconomics in its most gentile form.

A final example. A couple of hundred meters down the street from us is a small food market – one of three in the village. It is owned by a woman in her 80s named Ivana. She is friendly, sweet, and very helpful. But she speaks only Italian and sometimes in the local dialect. So, I have worked to improve my Italian so I can make my shopping needs clear. Buying food from Ivana is always a treat because she approaches me with a big smile and offers to help me find items.

Every few weeks we buy brown eggs from Ivana. She gets them delivered from a nearby farm, and they have bright orange yolks – a delightful visual experience as well as a splendid gustatory one. I watch her as she carefully selects each individual egg from a stack of carboard pallets. I bring my own egg container with recessed pockets that she carefully fills. She charges 3 euros for 10 eggs and has not raised her prices in years. So far, this is an unremarkable food transaction, quaint though it may be.

But one night, around eight, I answered a knock at the front door, which is unusual. It was Ivana. She had brought us a bag full of her eggs. I was momentarily speechless. I had never in my life had a shopkeeper hand-deliver eggs to my doorstep. I guessed that she had just received a delivery and wanted to be sure we got a good pick. I thanked her profusely and dug three one-euro coins out of my pocket. The price hardly matched the thoughtful, personal gesture.

My wife can easily cite dozens of other examples of this personal, face-to-face form of commerce. She provides herbal medicines to local people and lets them decide what to pay, based on their financial situation. She also grows a massive sage plant in the garden and frequently cuts a bouquet of leaves to give to the chef at another local restaurant. The woman promptly fries them in a feather-light batter as antipasti. Sometimes, we are served our own harvest.

My colleague and friend David Leland, who is a wise economist, confesses little knowledge of nanoeconomics. However, he has observed: It embodies “compassion, understanding, mutual caring, love, and generosity. The actual outcome of the transaction is minor, compared with the shared bonds of the people involved.”

The Scottish historian and writer Thomas Carlyle once called economics the “dismal science,” with its relentlessly stark and cruel use of quantitative metrics to describe human life. Perhaps nanoeconomics is its secret progeny — both humane and hopeful.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Over the last 30 years, Seattle built an economy, and unbelievable riches for some, hell bent on destroying mom and pop business world wide. Moving to Italy isn’t really an option for most of us……

Kindness economics.

I used to be impressed that economists could put a dollar value on something like knowing that an environment is pristine.

Now I’m more impressed with nano economics.

I love that you spread your art around. That’s wonderful.

How sweet. Of course there are communities even in high tech Washington State where Mr. Hinshaw would find nano economics practiced, believe it or not. It must be remembered that retiree Hinshaw’s ex-pat Italy is heavily subsidized by those working drudges in Northwestern Europe, via the European Union, supporting this enchanting community-building in what was once a nation of feudalism and dictatorship. According to the Economist Magazine’s 2019 Pocket World in Figures (its last pre-pandemic analysis), today’s Italy has a declining, elderly population with far more deaths than births, a chaotic, far-right political tilt, and a struggling GDP. It is a lovely, affordable retirement haven for ex-pats to be sure, where it is possible to look the other way. But this is a culture that in recent memory gave us Bentio Mussolini, Silvio Berlusconi, and today, the right wing “Brothers of Italy” under the Trumpian leadership of Georgia Meloni – soon projected to take elected control.