Some argue that President Vladimir Putin should be killed, but this would be a disaster (as I explain below). Recall that in popular nationwide elections, Vladimir Putin was voted president in 2000, 2004, 2012, and 2018, even though charges of fraud and voting irregularities shadowed the last two elections. Killing Putin would just perpetuate Russia’s chronic problem of negotiating peaceful transitions of regimes.

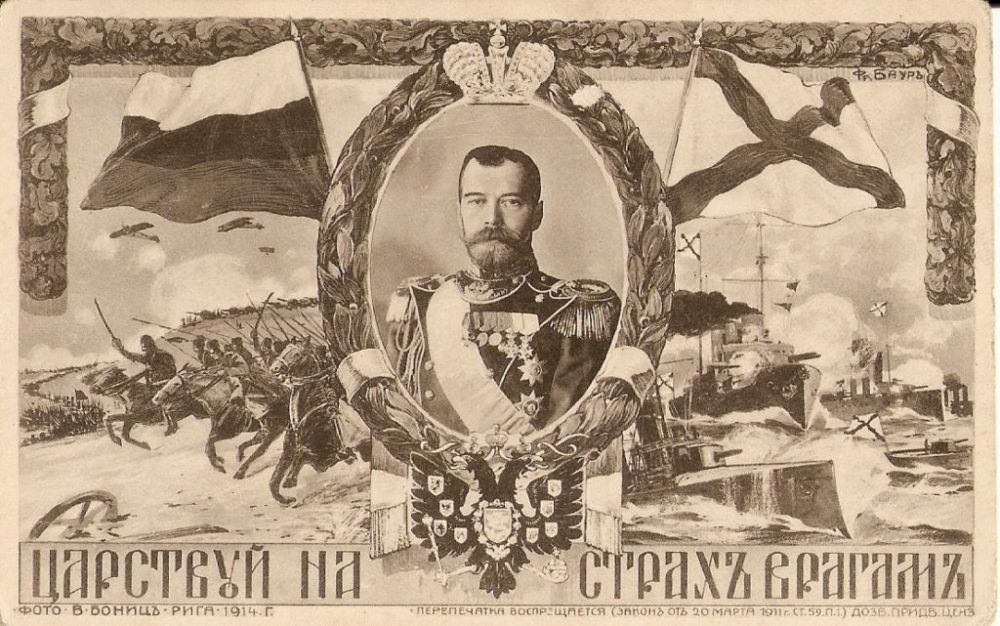

Russian history is marked by violence and assassinations. The abdication of Czar Nicholas II on March 15, 1917, in the midst of World War I, ended the autocratic 300-year Romanov Dynasty but didn’t spare the czar and his young family from a brutal massacre by the Bolsheviks a year later.

In place of the czarist leadership, the Russian Duma, the parliament, formed a Russian provisional government in February 1917, led by Alexander Karensky. That lasted a mere nine months until Lenin’s Bolsheviks seized power in the Great October Revolution. After a civil war killing millions, the victorious Communists organized a police state in 1922, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which endured until December 1991.

There was a brief period after the death of Stalin in 1953, when the terror by which he ruled lessened, initiated ironically by Lavrenty Beria, Stalin’s dreaded secret police chief, but led by Khruschev after Beria’s execution. In this lull, millions of prisoners in the Gulag were released and censorship was relaxed. Even Stalin wasn’t murdered. When he had a stroke in his dasha outside Moscow and his terrified associates left him lying on a couch for three days before calling in equally terrified doctors, the most they could have been charged with was negligent homicide.

Another respite came when the primary governing figure in the Soviet Union was Mikhail Gorbachev, elected by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as First Secretary in 1985 and later to become the eighth leader of the Soviet Union. Relatively young at 53 and a well-educated advocate for reform, he emphasized the themes of perestroika, “restructuring,” uskoreniye, “acceleration,” and glasnost, “openness.” Gorbachev rapidly gained popularity abroad, but the reforms he championed were unable to overcome the enormous inefficiency of the Soviet economy and the long-suppressed rage of oppressed ethnic nationalities.

As the Soviet economy began to collapse, the Soviet Union itself began to disintegrate – first in the Caucasus, absorbed by Imperial Russia in the late 19th century, and then in the Baltic states, seized by Stalin in 1940. In January, 1990, Soviet Special Forces and 26,000 troops invaded the city of Baku on the Caspian Sea to put down an anti-Armenian pogrom, shooting hundreds, mostly Azerbaijanis (Azeris), in what became known as the Black January massacre. Days later, the Azeri-majority Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic bordering Iran announced its intention of leaving the USSR.

On March 11, 1990, Lithuania declared its independence. Early in 1991, on what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” Soviet troops attempting to seize a television station killed 14 and wounded 140 in Vilnius, the capital. Lithuania claimed to be independent and Estonia and Latvia quickly followed.

The next bloody episode involved an August, 1991 coup against Gorbachev, including tanks deployed to the “White House,” the Russian Republic’s legislative building. That coup against Gorbachev, organized by disgruntled Communists and military units aimed at preventing a breakup of the 15-republic USSR, failed to oust him or to halt the rebellious republics from seceding. Gorbachev resigned as the last president of the Soviet Union at midnight on Dec. 25, 1991 and handed over the nuclear launch codes to Boris Yeltsin, elected head of the new Russian Federation. Next day the red flag of the USSR descended from a Kremlin tower, and the Russian tricolor took its place.

That transfer of power was surprisingly peaceful, and 1,000-year-old autocratic Russia morphed into a modestly democratic state. But only briefly. In 1993, a new Russian constitution was ratified, but Yeltsin violated it by dissolving Parliament, which then impeached him. Troops loyal to him shelled the White House, and he had the constitution rewritten to give the presidency more power. Economic chaos and bloody conflict in the Caucasus ensued until Yeltsin resigned in 1999, succeeded by his prime minister and chosen successor, Vladimir Putin.

The Tale of Bygone Days, an 11th-Century chronicle of early Russia, tells how in 862 eastern Slavs invited a Viking lord, Rurik the Varangian, to rule over them, “as we are unable to govern ourselves.” Since then, the Rus/Russians have only lived under powerful, oppressive rulers who argued that autocracy was the only form of government that worked with them. Putin is the latest embodiment of autocracy, seemingly determined to be counted among Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and Stalin.

It can be argued that in all their history, the few years when Russian people have known liberty, as we define it in the West, can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Is it even possible that an ancient British form of governance transplanted and elaborated in the United States is a plausible model for Russia, or, for that matter, China?

It is important to remember that the roots of our own constitution lie in the long and violent conflict between the British King and Parliament, which Parliament won only after the violent English Civil War of 1642-1661 and the Glorious Revolution of 1688. It took 500 years before a society emerged in which constitutional law could become a foundation for civil society. Even so, America has since endured genocides, a civil war that killed nearly a million, and rebellions, riots, and violent demonstrations in every year of our history.

Somehow, in some way, Russian politicians must find ways to enable the peaceful transfer of power before any form of civil society can emerge. Killing Putin would likely make things worse. Russians found a way in the 1950s and the early ‘90s. They need to be able to do so again.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“Somehow…” indeed.