In January 1999, I interviewed Jeff Bezos for a story in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He was 35, and at Amazon Inc., the average age was 29. Amazon was crammed into low-rent quarters near Pike Place Market, where the staff, including Bezos, sat at ersatz desks fashioned from 4×4 legs and low-cost interior doors.

Amazon had not yet made a nickel of profit but was already making $1 billion in annual sales. (It’s at about 700 times that, now.) Amazon stock was a rising star on Wall Street, and Bezos’ 41 percent share of it was already worth $9 billion.

Bezos wasn’t a Seattle guy. He’d been running a hedge fund in New York when he hit on the idea of a mail-order company to sell books. Why, I asked him, had he founded the company here?

The main reason, he said, was people. To grow the company, he needed a pool of the right kind of talent. Silicon Valley had a deeper pool than Seattle, but there were too many companies dipping into it, creating too much competition. Bezos had considered Portland, Reno, and Boulder, Colorado, but they were too small. Seattle had Microsoft and the University of Washington. Seattle was just right.

It was also just right for Bill Gates and Paul Allen to grow Microsoft, though they founded it in Albuquerque, New Mexico, because their first customer was there. They tried growing their company in the desert for three and a half years. When they moved it to Bellevue on January 1, 1979, they had 10 employees. Seattle was Gates’ and Allen’s hometown, but they had a business reason to move here. In Albuquerque, they were having a tough time recruiting high-value programmers.

Post Alley recently ran my article, “Seattle’s Next Big Thing?” I argued that we don’t know what our city’s “next big thing” will be. Civic leaders might say they do, and in hindsight, they might even be right. But they can’t know. History makes that clear. Too many times, when the city or the chamber of commerce has chased a specific industrial future, it ran down the wrong road.

What should civic leaders do, then? Seattle author David Sucher, who responded to my article, had the best short answer: “The worst thing that could possibly happen is for our political leadership to get involved with choosing winners and losers,” he wrote. “The best we can do (and it’s perfectly excellent, in fact) is to 1) support good schools and 2) preserve the rule of law. That’s what a public economic development program should consist of.”

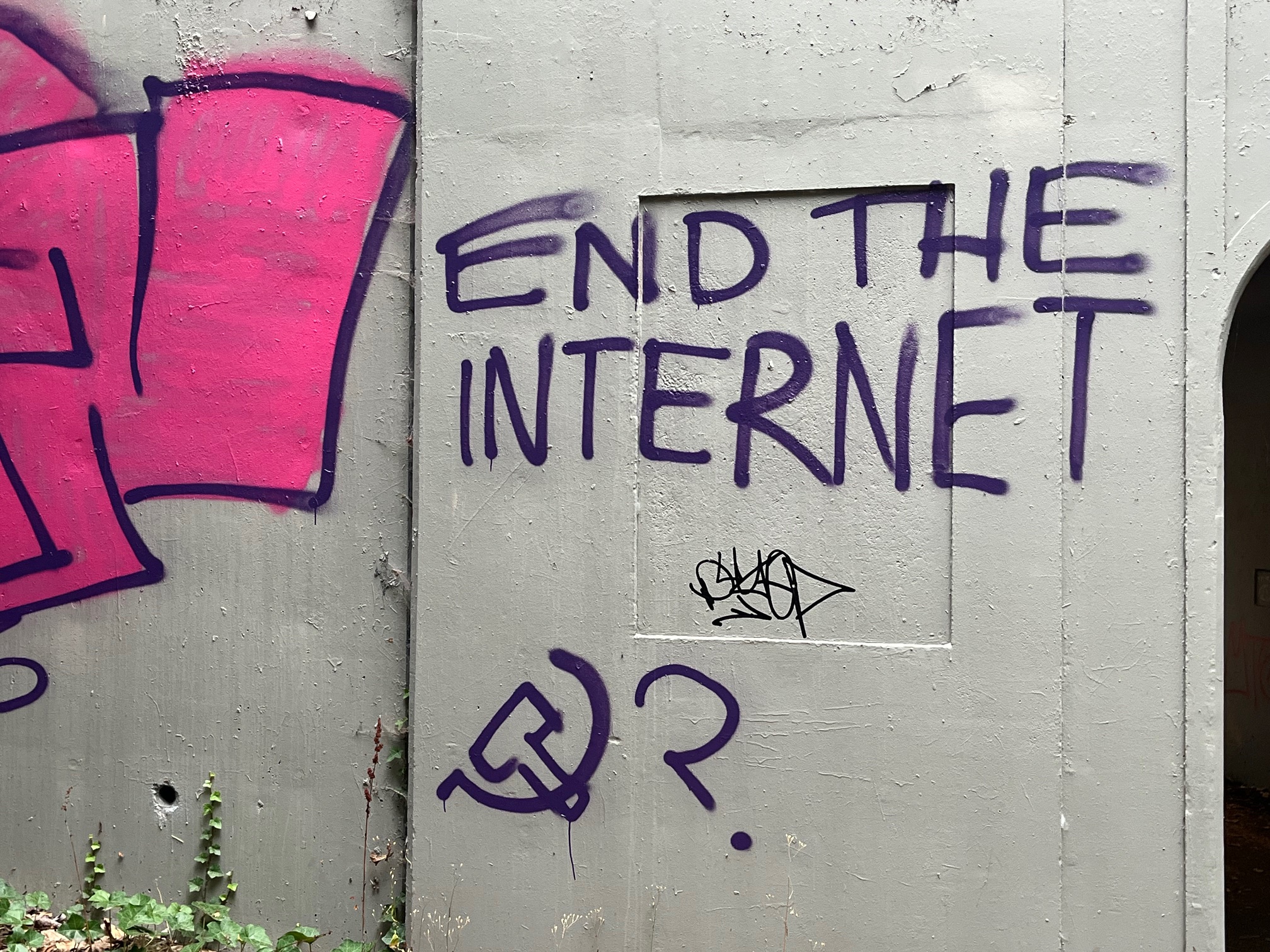

At a higher level in terms of big legal cases, the rule of law is much the same here as it has been. On the street, in terms of public decorum and safety, Seattle has fallen down. Downtown Seattle looks stunning from a distance, but up close it does not feel safe. There is no profit in blaming this on COVID-19; every American city suffered from it, but every city does not feel like downtown Seattle. That the vacancy rate in downtown office buildings has not recovered from COVID is related to the feeling on the street.

Regarding education, the world of work needs people who are literate and numerate, conscientious and responsible, and who can focus on a task and get it done. Much of this is learned at home and on the job. But education does matter. Seattle’s public schools are not all the same, and parents can find good schools if they make an effort. Students also need to make an effort, and many are not. Last year The Seattle Times reported a “school truancy crisis” of kids skipping classes.

In Seattle Schools, the dominant idea has been “No child left behind.” Helping the bottom quartile is important, especially when it is sagging, which it has been since COVID time. But the schools also need to challenge the top learners. For years, advanced learning in the public schools has been attacked as “elitism.” There has been a tendency to reduce rigor so that more students pass. The public schools still have some advanced-learning programs, thanks to the parents and teachers who have insisted on them. But these programs need to be on more solid ground. Industry is not egalitarian. Our industrial future — our human future — requires individuals who can do big things.

Still, Seattle people are more educated than in most U.S. cities. A study for WalletHub ranks Seattle 10th in educational quality among U.S. metropolitan areas. (Ann Arbor, Mich., was first; San Jose, second; San Francisco, sixth.) Partly because of the problems in the public schools, Seattle’s private schools serve an outsize 25 percent of the city’s students. Among U.S. cities, that’s double the national average.

The Seattle Times reported this a year ago, noting that in terms of the percentage of students going to private schools, Seattle is No. 2 among the top 50 U.S. cities, after uber-progressive San Francisco (30 percent). It’s politically incorrect to say so in this left-leaning town, but our city’s private schools are a civic asset.

So are many of its immigrants. All of the world’s great port cities — and Seattle is a port on the Earth’s largest ocean — are polyglot cities. Foreigners bring new practices, ideas, and connections that help local institutions sell products and services abroad. Google AI says more than half of Seattle’s software developers and one-quarter of its construction workers are foreign-born. Bill Gates and Paul Allen were born in Seattle, but Microsoft’s CEO today, Satya Nadella, was born in India. To compete in the world, you cannot cut yourself off from it.

It’s also good to know the world. Among the states, Washington is 8th highest in the percentage of its citizens with passports — 61 percent. That’s another asset.

A city’s most vital sales are of products that bring in outside money. That we bake our own bread and brew our own beer is good, but to compete in the world we need to sell to the world. And we do. Nearly half of Microsoft’s sales are abroad; at Boeing Commercial Airplanes, the proportion is 70 percent. At the University of Washington, 16 percent of students are from abroad, with the most from China, India, Taiwan, and South Korea. In economic terms, each full-tuition foreign student is an export sale — and a possible future asset.

Seattle is also a sanctuary city for illegal immigrants, along with San Francisco and Los Angeles. Setting aside whether cities should attempt to nullify federal law, it’s clear that Seattle has a strong interest in keeping open the doors for legal immigration, especially for those who are educated in our universities. President Trump’s immigration policy, including time limits placed on student visas, is a threat to this city’s future. So is our Republican president’s erratic and whimsical push for high tariffs, which are blockages on trade. At the moment, about all our Democratic delegation can do about this is to make a noise — and good for them!

Taxes can also help or hinder a city’s economic future, though there are arguments about how much. Republicans said for years that Jeff Bezos founded Amazon in Seattle partly because Washington had no state income tax. Democrats responded that in 2018, when Amazon was evaluating East Coast sites for its “HQ2” buildings, one locale under consideration was New York City, which has federal, state, and city income taxes. (Amazon has since backed away from New York, for other reasons.) Republicans responded, in turn, that when Bezos moved out of state in 2024, his obvious motive was to avoid Washington’s top rate on estates of 35 percent, and a top rate on capital gains of 9.9 percent — rates that are zero in his new home state, Florida.

Seattle has been imposing its own taxes, most recently a voter-approved 5 percent Social Housing tax aimed at companies that have employees who earn million-dollar salaries. Always, when the dollars fall short of political wants, our city council pushes to raise taxes (even when they say they are lowering them). It’s been 15 years since the council had to cut the budget in a recession, and no one with that experience is still there. Our council has been floating on the foam of a commercial boom, heedless of what might happen in the next recession.

Still, over the years, Seattle industry has paid up and kept on. In a list of America’s top 50 cities compiled a year ago, our median household income was third-highest, $120,608, behind only San Francisco and San Jose. Including its suburbs, Seattle people have built world-competitive companies: Boeing, Microsoft, Amazon, Costco, Starbucks, REI, Paccar, Nordstrom, Weyerhaeuser, Alaska Airlines, Tableau, and such nonprofits as PATH, the Gates Foundation and Fred Hutch.

What about our left-wing political culture? Does it matter? Seattle was long a liberal-Democratic city, and for business, it wasn’t a problem. But in the past 15 years we have seen the rise of a de facto socialist party. Voters elected councilwoman Kshama Sawant, a self-declared Marxist who was proudly not a Democrat and in 2024 did not support Kamala Harris. Not since the late 1930s has Seattle had a Marxist on the city council. Regarding the city’s most successful entrepreneur, Sawant famously declared, “Jeff Bezos is our enemy.”

Did that matter? During Sawant’s time in office, it didn’t seem to. We had our high incomes, our world-beating companies, and our deep pool of talent. Business was in a kind of ecstasy. Even today, after the tech boom has cooled and Covid has left one-third of the downtown office space vacant, our skyline is a billboard for American capitalism. As are our sky-high rankings in education and household median income, and our No. 8 ranking in gross private wealth ($800 billion) among U.S. metro areas.

Now, Seattle voters are on the verge of electing a socialist mayor. Again: Does it matter? Do the city’s business leaders care? It would be interesting to ask Jeff Bezos, but he isn’t one of them anymore.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

It’s a great question and in some ways you tip your hand on your ideological lean: should the people of Seattle be in service of “success” or should success be in service of its people? At a basic level, I think we’ll be considered “successful” on paper so long as the same old economic engines continue to churn out money and activity—our universities and their research arms, industries and natural resources (inclusive of tourist draws and the port). Our population continues to climb, as does the price of everything.

But I think we’re losing out on other important qualities that can’t be boiled down to public safety statistics or public school enrollment. Seattle used to have a creative scene. Seattle used to have a functioning low income housing ecosystem (remember those SROs on Capitol Hill?). I think Seattle has fallen victim to its own affluence now that every spare warehouse in the city has been bulldozed for apartments, and you’re more likely to hear the next table at a coffee shop talk about a new app or IPO price rather than idea for a book, or an up and coming Seattle band. We have many smart people here, sure, but I think we underestimate the hazards of becoming boring people.

Last point — we need to improve our schools on their own merits and for our children, not because they’ll serve Seattle. As you mentioned, we’re a city of immigrant workforces (domestically and internationally) and successful Seattle natives are probably most notable for being artists more than businessmen people. Schools are definitely rough around the edges, but I’ve got two grads who each benefited from both the “highly capable” end of the spectrum (AP opportunities abound) and vocational/post high school training programs. Good program options are there if you seek them. My biggest worry for our public schools is how they will survive the falling birth rates and families who move to more affordable cities.

Thanks for this thought provoking piece.

Yes, Wilson looks like a good bet to be the next mayor, but no, she isn’t the Return of Kshama.

Post Alley suggests Related Articles for me here, and one of them is Nick Licata’s “Lets Talk Bogeyman: Here’s What Socialism Is (And Isn’t)”. Might help to read that, for people who think an adequate political analysis here is “remember Kshama!”