News from the Russia-Ukraine War has down-paged America’s contentious wedge issues. But even if cultural wars aren’t daily making front page headlines, we’re still faced with ever deepening divisions.

Renewed recognition of the chasm came last November when Glenn Youngkin won the Virginia governor’s race by sounding the alarm about what he called “a war on families.” He promised to affirm rights of parents to make decisions about masks in schools. He vowed to end vaccine mandates and to ban “critical race theory” in public education, even though the theory wasn’t taught in Virginia’s K-12 schools.

Youngkin’s victory showed that politicians can manipulate voters using cultural wedge issues. Originally thought a moderate, Youngkin used one of his final television campaign ads to catalog a mother’s attempt to have a novel removed from her child’s English curriculum. The ad didn’t point out that the “child” was a high school senior in an advanced class or that the book shown was Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize-winning novel “Beloved.” Once in office, Youngkin set up a tip line that allows parents to report “divisive practices” in schools.

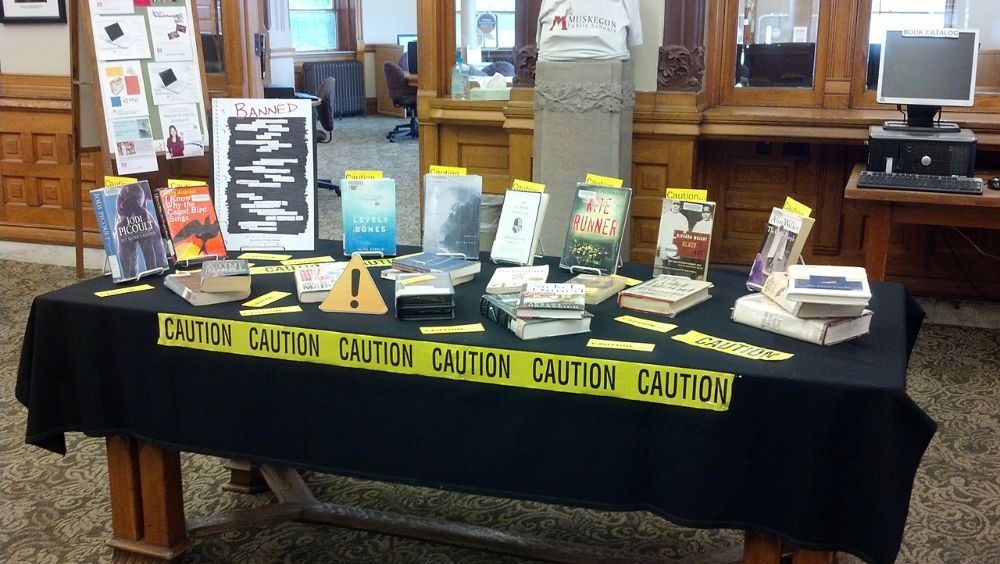

Youngkin’s tactics parallel other conservative efforts to remove certain books from school curricula and libraries. America’s recent book bans are aimed at schools, teachers and libraries. The strike on award-winning literature — seemingly no classic is safe — has gained strength at a pace not seen in decades. The American Library Association reports 330 book challenges last fall from September through November.

What led to the surge? Advocates for free expression such as PEN America and the American Library Association say censorship attacks are driven by social media, pushing challenges into state houses, law enforcement and political races. Groups such as “Moms for Liberty” and “No Left Turn on Education” are leading the charge against teaching materials. Librarians and educators get caught in the middle.

Yael Levin-Stauss, Virginia chapter president of “No Left Turn,” claims schools are “indoctrinating kids into dangerous ideology, spreading radical and racist ideas.” Levin-Stauss’ targets include Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” and Robin Diangelo’s “White Fragility.”

Governors across the South have joined the censorship fight. Texas Gov. Abbott directed the state education agency to investigate public school libraries and yank books with so-called “pornographic content.” South Carolina Gov. Henry McMasters told the superintendent of education to root out what he identified as “obscene and pornographic” material in schools.

Not to be outdone, Texas Rep. Matt Krause drew up a list of 850 books that he identified as causing students to feel discomfort, guilt, anxiety or any other former of psychological distress because of race or sex. The San Antonio School District pulled 400 of those books from libraries without any formal review process or specific complaints.

While conservative areas excel at censorship, it’s important to recognize that liberal communities, have their own blots. The cancel culture on college campuses has come in for a deserved share of criticism. So too have “woke” student demonstrations opposing appearances by right wing speakers on campuses.

Book bans aren’t unknown in liberal communities. Oakland, Ca. schools banned Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple,” citing sexual and social explicitness. Issaquah removed J.D. Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye,” for “immorality and profanity.” Burbank, Ca., targeted John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” while the Mukilteo School District removed Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” from its 9th grade curriculum for racial slurs and “white saviorhood.”

History tells us book banning is hardly new. Since the 16th Century, the Roman Catholic Church has been proscribing “malicious publications” such as the works of John Locke, John Milton and Victor Hugo. First translation into English of The New Testament was banned in England and its translator executed for heresy. The U. S. Post Office banned books considered obscene in the 1920s, going so far as to burn 22 copies of James Joyce’s “Ulysses.”

In a recent New Yorker article, Harvard history Prof. Jill Lepore revisits the 1925 Scopes trial, the anti-evolution campaign and how fundamentalists of that day were concentrating on emasculation of textbooks, the purging of libraries and the continual hounding of teachers. Lepore concludes, “It went on a long time. It’s still going on.”

The right-wing’s recent interest in banning books — many of which have been on shelves for decades — suggests there are hidden agendas. This sudden upsurge of school library and curriculum issues in Red states constitutes a veiled threat to public education, an excuse to replace our system of public schools with privately-run educational systems. One example is Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee’s announcement that he has approached a Christian college in Michigan to open 50 charter schools in his state.

Other political observers believe books bans — responses to Youngkin’s so-called “war on families” — are designed as a wedge issue to leverage votes in suburban areas. Groups like “No Left turn on Education” most certainly will weigh in with partisan backing in the nation’s midterm election.

There’s a not-so-subtle racism and sexism, not to mention homophobia, to book banning. Black and minority authors have been disproportionately targeted, seeking to marginalize their voices. The top ten most-banned books of 2021 included books by Toni Morrison, Ibram X. Kendi and Angie Thomas.

On the positive side, the book-banning surge has fueled renewed efforts by backers of free expression like PEN America, the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) and the American Library Association. PEN (“poets, essayist and novelists”) is benefitting from a recent donation by Markus Dohle, chief executive of Penguin Random House. He has created the Dohle Book Defense Fund to support communities where books are being challenged. He donated $100,000 and has pledged a minimum of $500,000. For Dohle, book banning is a professional and personal issue. Raised in Germany after World War II, he grew up of the “dark times and dark history of the country” and has worked in restricted environments, including Poland in the 1990s and Russia in the early 2000s.

Calling the wave of book-bannings “unprecedented,” PEN chief executive Susan Nossel reports the organization has hired more workers and consultants to address it. She said, “In previous times we’d deal with a few of these situations a year. Now we’re dealing with new challenges and bans on a much larger scale. It’s not just parents; it’s legislation being introduced in statehouses to impose sweeping bans on what kinds of books are available to students.”

The ACLU has jumped into the fight. The agency is suing in federal courts to prevent school districts from removing book and has filed records requests in Tennessee and Montana over book bans. Recently ACLU lawyers sent a letter warning Mississippi against “unconstitutionality of book bans,” based on a 1982 Supreme Court ruling that school boards can’t remove books from library shelves simply because they dislike ideas in the books.

The silver lining on this gloomy front is that book bans very often backfire. A recent example followed Tennessee’s McMinn County school board banning of “Maus,” Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel about the Holocaust. Just after the news broke, “Maus” sales skyrocketed. It became the No. 1 Amazon best seller 36 years after it first appeared. Bookstores in Nashville and Knoxville arranged to send a free copy of “Maus” to any student requesting one while other book sellers were sending a percentage of sales to the Freedom to Read Foundation.

Reading banned books, particularly significant ones like “Maus,” Khaled Hosseni’s “The Kite Flyer” and Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” has the appeal of a guilty pleasure. I remember reading my first banned book as a young teen. I had swiped my mother’s copy of “Forever Amber” and read it by flashlight under the bedcovers. (Not only was Kathleen Winsor’s novel banned in 14 states but Catholic priests said anyone who attended Otto Preminger’s movie “would go straight to Hell.”) Only mildly salacious, the book was actually a well-done historical account of the 17th Century plague and the Great Fire of London. One postscript: After my sneaky clandestine read, my mother handed me “Forever Amber” and said I might find it interesting.

Frankly it would do us all good to read, promote and distribute banned books, contribute what we can to defense funds and defy those trying to control young minds.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This librarian wants to thank you for framing this so well and giving us some optimism —counter efforts by donors and agencies, and a rise in book sales for banned books.

Although a librarian I’m not, I agree fully with this comment, and intend to continue spreading the word to counter this craziness.

Heterodoxy is hard! At the same time, it just always feels uncomfortably wrong when zealots (right or left) insist on mass/forced-conversion of non believers.

On a lighter note :

I remember as a 13yr old sneaking into the theater to see “The Moon is Blue” because it was on the LofD condemned list. I kept waiting for the good parts that never came.

The use of the phrase ‘Are you trying to Seduce Me’ went over my head………at the time.

“Why now?”

One reason is that Democrats – THE party of reason in America — have narrowed the range of “legitimate” discussion.

Mainstream Democrats & liberals refuse open & robust discussion of significant & highly-charged issues (such as CRT, gender identity, affirmative action) and even declare such discussion as inherently bigoted, well then you leave the field open for right wing extremists.

It’s perfectly reasonable for the Democratic Party to adopt policies which not everybody in the Party likes. But foreclosing discussion is not the way to make a stronger party.

So we shouldn’t be surprised when the extremist Republicans take up the slack. It’s politics And that is exactly how it is supposed to be played. So we are getting exactly what we ask for.

Thanks for this story.

I also read the Jill Lepore story in The New Yorker and it’s definitely worth reading or listening to. One of the points that I found most interesting is that much of the sound and fury about the evils of public education and the need to ban books seems to be coming from a very small but vocal slice of the population:

“And yet, in “Making Up Our Mind: What School Choice Is Really About,” the education scholars Sigal R. Ben-Porath and Michael C. Johanek point out that about nine in ten children in the United States attend public school, and the overwhelming majority of parents—about eight in ten—are happy with their kids’ schools. In the name of “choice,” a very small minority of edge cases have shaped the entire debate about public education.”

Many of the complaints that come out of the far right, from the myth of widespread election fraud to the life-destroying power of cancel culture, are grossly exaggerated to whip up support by spreading panic among the uninformed.

I’m not sure where you get your numbers, but over the last 25 years there has been a revolution in public education. Although the pandemic has caused a flat spot in enrollment, charter schools are future, like it or not. https://data.publiccharters.org/digest/charter-school-data-digest/how-many-charter-schools-and-students-are-there/

Jill Lepore got her numbers from the source she cited and I reiterated in my comment. Neither us is arguing that charters schools are not the future. They may well be. What she is arguing–and I am agreeing with–is that that future might not be a such good thing for everyone.

There was an opinion piece in the NYTimes today that deals with this issue as well. It’s well worth reading: If You Think Republicans Are Overplaying Schools, You Aren’t Paying Attention. Unless they have put up a paywall, you can find it at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/21/opinion/democrats-public-education-culture-wars.html

Just read the opinion piece article you suggested By Jennifer C. Berkshire and Jack Schneider and especially appreciated this:

“Schools may not be able to solve inequality. But they can give young people a common set of social and civic values, as well as the kind of education that is valuable in its own right and not merely as a means to an end. We don’t fund education with our tax dollars to wash our hands of whatever we might owe to the next generation. Instead, we do it to strengthen our communities — by preparing students for the wide range of roles they will inevitably play as equal members of a democratic society.”