Of late it seems no one in Seattle feels represented by local government. Progressives say the city council should be moving further left and faster, blaming the mayor for slowing progress. Conservatives feel left out of decision-making. Those in the middle are frustrated by well-intentioned policies that reduce personal and economic security and their faith in government. Our electoral system has not evolved to ensure election results reflect majority opinion or a fuller range of views.

One problem is our top-two primary system. Broad-based support is not required to win since candidates from the same party can get through crowded primaries with a narrow base of support. As a result the general election is a contest between two candidates who can be unrepresentative of the broader electorate, leaving voters not liking either candidate. This was my experience in the 2017 mayoral election when Jenny Durkan and Cary Moon got a combined vote total in the primary of 45 percent, meaning 55 percent of voters preferred someone else as their first choice. In the general election, Durkan narrowly won and barely expanded on moderate voter turnout over the primary. She still struggles to achieve sustained support.

A similar phenomenon occurred in the high-profile 2019 District 3 City Council race where socialist Kshama Sawant won the primary with 37 percent of the vote. In the general election she won with 52 percent of the vote and remains a polarizing figure with widespread disapproval beyond her district. The loser failed to expand moderate voter turnout beyond the primary.

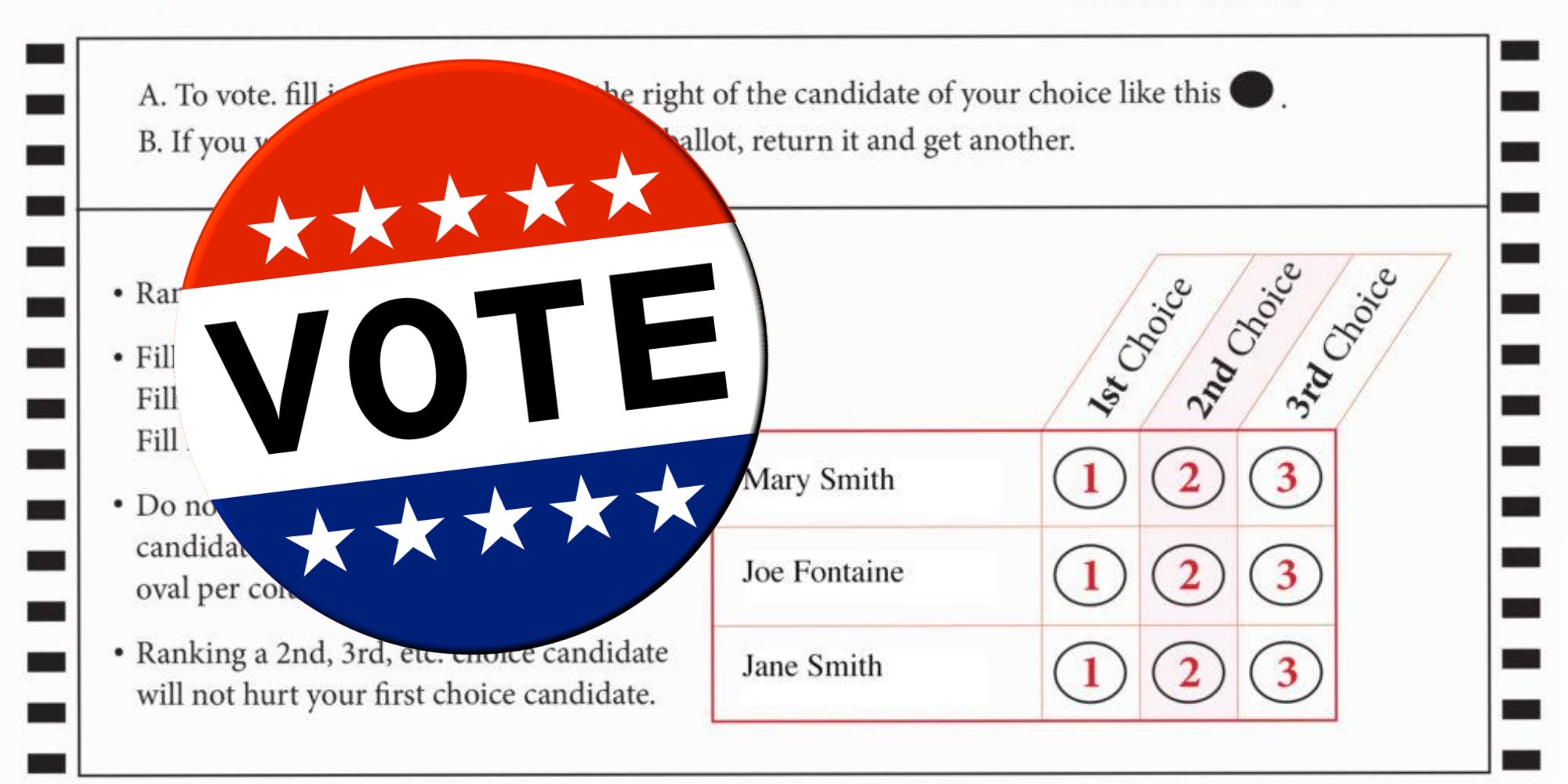

One increasingly popular way to address this problem is to give voters more choices on the ballot by means of ranked-choice voting (RCV). With RCV, voters rank candidates in order of preference, allowing them to more fully express their opinions. Votes are counted in rounds. All the first preference votes are tallied, and if no candidate has over 50 percent support, the last place candidate gets eliminated and their votes are transferred to the voter’s second favorite candidate. The process continues until a candidate has over 50 percent of the vote.

RCV induces candidates to build broader coalitions to win elections. They can’t win by just energizing their base. Instead, they must appeal to a wide coalition of voters to win second and third choices. If either of the races discussed above had used RCV, voters might have had more options on the ballot, moderate voter turnout would likely have been higher, and everyone would better understand the source and strength of the winner’s support.

Some critics point to the way campaigns can game the system under RCV. For example, in San Francisco’s 2017 mayoral election, two candidates with similar platforms began campaigning almost as a team, urging voters to rank one of them first and the other second. Advocates argue that this is exactly the way campaigns should work. Under our current system, candidates are punished for agreeing with each other because it splits the votes of potential supporters. With RCV, similar candidates can all remain in the contest without siphoning votes from each other.

RCV isn’t revolutionary. It has been used for years across the U.S., including in over a dozen cities. In 2019, New York City voted overwhelmingly to adopt it, making it the largest jurisdiction to take up the reform. Maine uses it for many state and federal offices and voters in Alaska and Massachusetts will be voting on it for state-wide use November 3rd. Voters have approved RCV at the ballot because it promises to increase voter engagement, create less hostile campaigns, better represent historically marginalized communities, boost voter turnout, and save money by eliminating primary elections. Significant majorities of voters who have used RCV want to keep it.

While RCV would favor elected leaders who enjoy deeper and broader support than our present system, a single individual may no longer be able to adequately represent the majority of voters. RCV can help, but not solve, this problem for single-seat positions such as mayor but can be effective for multi-seat elected bodies such as city councils.

RCV, when used in multi-winner at-large elections, ensures the elected body more fully reflects the diversity of the electorate. Using this approach in Seattle would require a different structure to the council. There are many options, but here are two: Reverting to an at-large council structure with a portion of the council elected in each election; or using fewer, larger districts with multiple at-large members from each. Candidates would run for all the available seats, and voters would rank all candidates they support.

The resulting council would more fully reflect the ideological makeup of the city, and far more Seattleites would have someone on the council they felt shared their interests and ideology. Such a council would presumably find it easier to work collaboratively, bridge ideological differences, and resolve major problems.

Multi-winner ranked-choice voting is one of the key recommendations in the recent report from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences’ Commission on the Practice of Democratic Citizenship. In their words, “If [multi-winner districts,] were coupled with ranked-choice voting in congressional elections, they would encourage the participation of a wider array of candidates, each of whom would have to appeal to a more heterogeneous bloc of voters.”

While the report focused on congressional races the concept is applicable to any elected body. In fact, we could also consider these reforms for School Board, King County Council, and Port Commission elections, where better representation of Seattle’s increasing diversity is also needed.

Robert Poore’s article here gives a clear description and a compelling argument for ranked-choice voting, pointing out that it has been successfully used elsewhere – often for many years – in multiple ways.

Washington state’s current election procedures – in stark contrast to many states – are exemplary: easy voter registration; open, not party, primaries (favoring more moderate, less ideological candidates); no arbitrary voter-access requirements; and long experience in vote-by-mail. Perhaps it’s time to consider another step forward.

Robert Poore’s articles does do a good job of describing ranked-choice voting and the arguments in favor of adopting it. As a balanced argument the article falls far short, however. There is a large body of literature which points out problems with ranked-choice voting, and the article fails to note that some jurisdictions which initially adopted such a system repealed it at a later date. A lot more work needs to be done to address the problems of ranked-choice voting before there is a headlong effort to get it adopted.