Gordon Walker may be the most famous Northwest architect you’ve never heard of. He lives on Orcas Island and works behind the scenes at Mithun, an architecture firm that has headquarters on the Seattle waterfront. No firm bears his name these days. Walker has not been adept at the celebrity game, but he is revered among other architects, especially in Seattle. It’s time you met him.

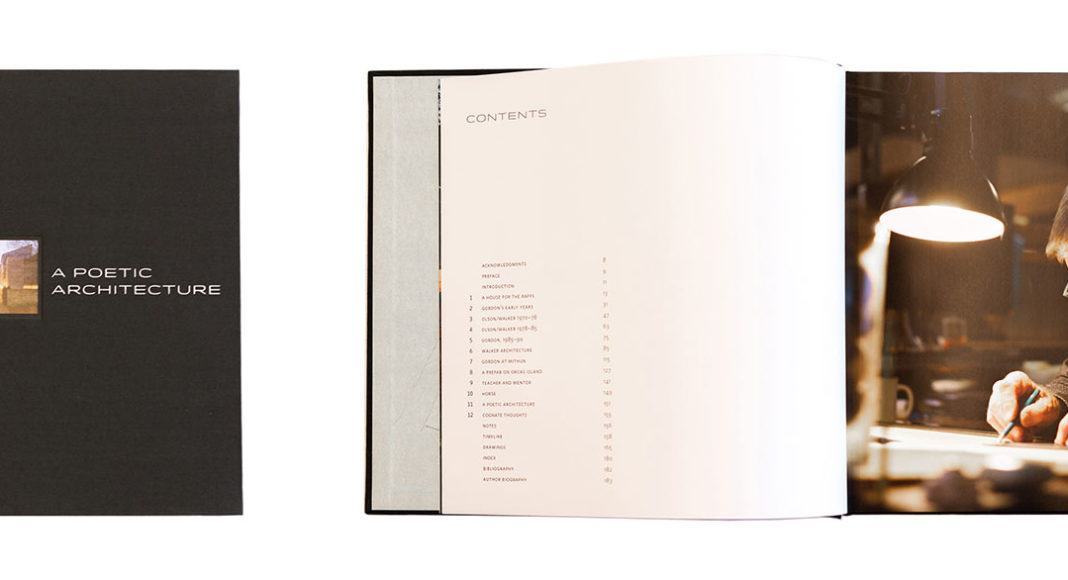

Fortunately, author and teacher Grant Hildebrand has written a new book, Gordon Walker: A Poetic Architecture, (Arcade, Seattle). It’s a labor of love and a personal tribute based on many lunchtime conversations. It’s also a great way to understand Walker, his life’s work, and his ongoing influence in Northwest design culture.

Gordon Kendall Walker was the first of four sons born to a mortician, Harlan, and a beautician, Margaret Louise, in Des Moines, Iowa, 1939. The family left two years later so Harlan could train for the US Navy near Lake Pend Oreille. They never left Idaho, and Gordon had a hand in turning an abandoned company town called Talache into a successful fishing resort, even as he played all-state center and raised goats on the side. He studied in a five-year architecture program at the University of Idaho and graduated in 1962. This pied piper of Northwest architects is beloved for his pranks. At his fraternity, Walker conspired with neighboring women to turn on powerful flashlights at his signal and illuminate the peering faces of his brothers. Later he would challenge a friendly client by sneaking onto a job site and applying forbidden black raspberry paint to the walls of the Mark Tobey Pub.

At some time during his Idaho years, Walker began to develop his distinctive modernist values: blending plan with landscape or cityscape, bringing light through interiors and framing views, and making limited spaces seem large. Peaked roofs and punched windows and doors are out. Enclosed rooms are a grudging concession to privacy. Decoration is forbidden. Tradition is suspect. Weather protection can’t be ignored, but it no longer drives everything. Materials and craftmanship have never been more important. Got that?

Walker admired Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn, who liked concrete a lot. But Walker also got caught up in the mystique of the legendary Northwest style, also called “stick modern” because of expressed wood structures like University Unitarian Church by Paul Hayden Kirk. He came to Seattle and moved easily among the architects who were putting the city on the map in the 1960s, even before he had obtained his professional license.

Like others in his cohort, Walker liked to use cheap, traditional materials in non-traditional ways. He had a concept for a cinderblock house, but he could not find a general contractor who would build it. He found a mason instead, and joined him at the Queen Anne site himself, staying two steps ahead on the design details while carrying hod and lacing re-bar through the courses. As Hildebrand recounts it, the experience was creatively formative. Also cold and wet. Walker soon decided to sit for the licensing exam and rejoin the professional class, indoors.

Doug and Kathie Raff, the young couple who bought the Queen Anne house, moved in—but the skylight over their bed leaked. Walker found a master roofer and got it fixed, and the Raffs still loved it. At the time, modern architecture was nothing if not transformative, and radical projects like the Raff House demanded belief from owners, too, especially ones with skeptical neighbors. The Raffs may not have known it, but they were art patrons, finding commonality with the faith of artist in his work. They enjoyed their new life, commissioned a second home by Walker, and ultimately sold the Queen Anne home. The new owners got wet. “Yeah, the roof still leaks,” said Walker. “Get over it.”

All in all, Walker is responsible for more than 30 residences (including several he built with his own hands), “a host of buildings and master plans” for university campuses, three buildings for the Pacific Northwest Ballet, many commercial structures, and a wine bar. Many of them have been newly photographed by Andrew van Leeuwen for Hildebrand’s book. Original drawings are reproduced, and at least one was newly drawn by the architect, from memory. Here’s a photo portfolio of his buildings.

Walker’s concrete blocks became a signature element for him through the years, even though he designed at every scale and with every material. One of the more visible examples of his exposed concrete block is the eight-story Pike and Virginia Building, at the north end of Pike Place Market (Olson Walker, 1978). Another is Nicholas Court (1413 15th Avenue), a small multifamily building designed with son Colin Walker (Walker Architecture, 2000).

Walker taught at the UW while practicing. Teaching comes easily, even naturally, to Walker—as his co-workers at Mithun attest. His former partners and design team members were clearly touched by his uncompromising creative vision as well as his charm and humor. Walker does not take himself very seriously, but his obsessive working style could conflict with other architects and corporate culture. And he began practicing at a time when Seattle firms—small, large, and extra-large—did not easily make space for back-of-house studio design partners like Walker. From his days as co-founder with Jim Olson of Olson/Walker Architects (now Olson Kundig) to his stint with NBBJ and his intervening years running his own firm, his career met some full stops before he found his current niche at Mithun, where he is able to practice and inspire others without managing a firm.

Professional design culture in cities like Seattle has become international and less regional. Modernism is no longer a movement; it’s now a standard. Architects are more diverse in gender, race and national origin, but perhaps more alike in class background. Design is largely automated, and context is data-driven. Sustainability and environmental responsibility are important as never before, which means regional sourcing. Poetry is not part of the program, or the language, save for exceptions like Walker’s “poetic architecture.”

Gordon Walker is still roaming from desk to desk on Pier 56—looking, mentoring, cajoling, and sketching. He makes the jokes but normally leaves the talking to others. In a moving preface to Gordon Walker: A Poetic Architecture, Pioneer Square bookseller Peter Miller, a boon companion of Walker, riffs on the title theme: “These are clever times—you can buy the clothing of poetics, but for the body and the soul of it, you can only do the work and hope and try. And believe.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Clair,

You have written a beautiful and short profile of Gordie. Many thanks!

Grant

Jones Riverbraids Arboretum in Oroville WA