Editor’s Note: this piece originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of PublicDisplay.Art, One Reel’s quarterly tabloid publication showcasing local art and artists, and is reproduced here with permission.

The editors of PublicDisplay.Art, knowing that I’ve invested energy and resources into collecting artwork by Seattle artists in my bougie middle age, asked me to write a piece encouraging you, dear reader, to do the same. Scratch an itch you may not know you have. Enrich your life by collecting art.

Because I genuinely believe that collecting art will enrich your life, whatever your circumstances, and because I’m getting paid to write this, I am going to convince you that it’s cool to buy and collect art. If the idea of owning art seems foreign to you, you’re not alone. It felt foreign to me, too, until it didn’t.

Let me explain.

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away (well, Portland, OR in the mid-1980s), a callow 18-year-old college student (who happened to be me) decided to take an “Introduction to Art History” class. I did this on something of a lark. I wasn’t a particularly artsy-fartsy type, and at the time, in my less than two decades of existence on this mortal coil, I hadn’t paid much attention to this thing we call “art.” Of course, this was true of a lot of other things as well; youth really is wasted on the young.

The instructor in that course was a bearded man with a plummy accent and a highbrow demeanor. His name was Charles Rhyne, and he (as I learned) was one of the world’s foremost experts on the paintings of an early 19th-century English landscape painter I’d never heard of named John Constable.

Despite my best thick-headed efforts to resist, I learned quite a lot from Professor Rhyne. I would never take another art or art history class again, and I admit I no longer remember all that much about Rhyne’s lectures, but I did retain a few things. Among them, I vividly recall him one day lecturing animatedly on the concept of “connoisseurship,” or the idea (as I understood it) that one can immerse oneself in a work or works of art so deeply that one develops a refined visual appreciation of that artistic work, to the point that one can almost intuitively distinguish between artists and styles and understand the essential nature of artworks.

So connoisseurship was some mashup of expertise and taste implying ownership and patronage. The greatest connoisseurs were collectors and art patrons, and the greatest collectors and patrons were connoisseurs. Or something.

About “connoisseurs,” Wikipedia tells me that the term “now has an air of pretension” to it. Well, either I was ahead of my time, or it did back then too. As Rhyne wittered on, I conjured up off-putting images of ruddy-cheeked, bearded white men (who looked much like Professor Rhyne) with plummy accents, dressed in smoking jackets or tailored tweed, in the library of the manor house snootily discussing “ahrt.”

The elitist vibe was initially off-putting. Not my scene, man. The idea of art collectors I took away from that lecture seemed fundamentally alien, a world of affected rich people congratulating each other on their good taste.

Except…

It started dawning on me, all those weeks that Rhyne projected images of masterworks on that classroom wall, that art is pretty cool. If you immerse yourself in art, interesting things happen to how you see the world. If you strip away the elitist connotations, maybe there is something universal in the idea of enjoying and appreciating art, something universal at the heart of what it is to be a connoisseur.

It was also dawning on me that art came in near-infinite varieties. Not all of it was high art, the stuff that fills museums and the homes of people with too much money. There was this whole other world of art on the walls of thrift stores, the rooms in tawdry motels, or downscale restaurants.

I didn’t quite understand it this way at the time—my vocabulary needed work back then—but I was discovering the concept of “kitsch,” which is, at its core, the idea that one can look at a piece of art and believe it to be both bad and good at the same time. And that it is possible to derive great pleasure and deep appreciation from loud, tawdry, or cloyingly sentimental art. It was possible to fall in love with the cheap stuff.

Being a mature and worldly 19-year-old, I was inspired. I decided to become a collector and set out to make myself a connoisseur… of kitsch. At a garage sale soon after, I came across a ludicrous three-and-a-half foot plaster replica of Michelangelo’s David on a plastic base, coated in gold leaf paint overlaid with a purple-and-green paisley pattern, a garish and psychedelic version of Michelangelo’s masterpiece. I thought it was exquisite! It spoke to me! (I was very busy kicking open the doors of perception at the time). I bought it for what then seemed like a princely sum of $75.

(A sad coda to this story: just a few weeks later, one of my housemates, shitfaced in our living room—don’t judge us, we were in college—fell on top of my David, shattering the upper half of this masterwork. Like a damaged sculpture from Greek antiquity, the legs and lower torso remained a treasured possession. Eventually, it landed in the basement of my parents’ home. I thought it would be safe there, but philistines that they were, they didn’t share my connoisseur’s eye and a few years later, during a clutter-reduction crusade, tossed it in the garbage.)

Be that as it may, I now had tasted blood and I wanted more. More, more, more! I quickly settled on an underappreciated area of art collecting that I would make my own: black velvet paintings, of course. I began to scour the city in search of the finest examples. I was committed to giving the great works by anonymous masters of this unsung medium their due. I acquired several big-eyed children, a touchingly rendered Elvis, a dashing toreador waving his red cloak before a raging bull, a large brutally orange rendition of the Golden Gate Bridge, an angry-looking Jesus who hung in the bathroom and whose accusatory eyes bore into anyone who committed the sin of peeing. And so many others.

O dear reader, how to convey to you the indescribable joy I felt when I acquired my boldly executed black velvet Stevie Wonder? Or the joy that my growing collection—soon, friends were gifting me black velvets they’d found around Portland – bestowed not only on me but on all the trashed undergrads who viewed them in our off-campus college house?

This was art collecting; this was connoisseurship! Maybe not exactly what Professor Rhyne had in mind, but still.

At the ripe old age of 23, I finally—again, despite my best efforts—graduated and moved away, leaving my collection behind. (True story: 20 years later, on a visit to Portland, a former housemate and I walked by the old house. We knocked on the door, and the clearly stoned kid who answered offered us a tour of the place. The house, already run down and none too clean when we lived there, was in dire condition: peeling paint, piles of junk, and holes in the walls. But my black velvet art collection was still hanging, mostly intact! “We love these paintings but had no idea where they came from,” the kid told us).

Post-college, I let my early foray into connoisseurship lapse, until about 10 years ago. One day in Seattle I was in a bar (some things never change), and there on the walls of the Virginia Inn were paintings for sale by a Ballard artist named Kellie Talbot. She specializes in photorealist paintings of old signs. I loved them, and was particularly drawn to the centerpiece of this barroom exhibition, Talbot’s rendition of the Seattle P-I globe. I dug it, but the painting was priced well outside the range of what I could afford. (It was purchased by some friends, who still have it hanging in the living room of their Pioneer Square condo).

But you know what? Soon after, I contacted Talbot, and she offered to paint a smaller version of the P-I globe for me for a much lower price. As a bonus, having commissioned this work, I got to influence the look and feel of the painting. She asked how I wanted the background sky to look (dark and ominous) and how much rust I wanted on the globe (lots). As a result, my version has a more decayed, almost post-apocalyptic feel than the sunny and nostalgic version my friends own. How cool is that?

That got me started again, this time collecting finer art. Not a ton, but a painting or two a year, mostly by Seattle artists. I only buy paintings I love, ones that, for some reason, make me want to dive into them emotionally. Usually because the work invokes some memory or some aspect of my life. It feels good to be supporting the work of local artists, but that’s not why I do it. I do it because there is a lot of joy in owning artwork that speaks to your self-conception, in which you can immerse yourself.

I splurged on a big painting depicting a broken branch on a rock beach by Fred Holcomb, a long-established Seattle artist who paints Northwest landscapes and who is represented by Linda Hodges Gallery in Pioneer Square, because the painting reminded me intensely of a spot I love on Orcas Island. I bought another Kellie Talbot painting of a rusting “LIQUOR” sign (I think I mentioned that I like bars).

If a low-culture vulgarian like me can indulge in cut-rate connoisseurship—for some inexplicable reason, my wife laughs uproariously every time the notion that I might have decent taste comes up—you can, too. Contrary to what you might assume, and what I used to assume, collecting art doesn’t need to be something only for the well-to-do, particularly if you’re willing to be creative and industrious about seeking out art. Nor do you have to go the kitsch route I did in my youth (though I still miss those black velvet masterpieces!).

What do I mean about being creative? I acquired two paintings at charity auctions, one by Anne Siems, a German-born artist represented by galleries around the country whose work, which is psychological and a little trippy with fairy tale overtones, I adore. And one by Liz Tran. Both are established, well-known Seattle artists whose individual works typically cost well into the four figures. I got both pieces for much less. Then, later, because I happen to have a pet tortoise (don’t ask), I splurged on a second Siems painting of a tortoise and bird surrounded by little cups and jars and falling droplets of flame, which invokes the sense of a magic spell. I mean, how could I not?

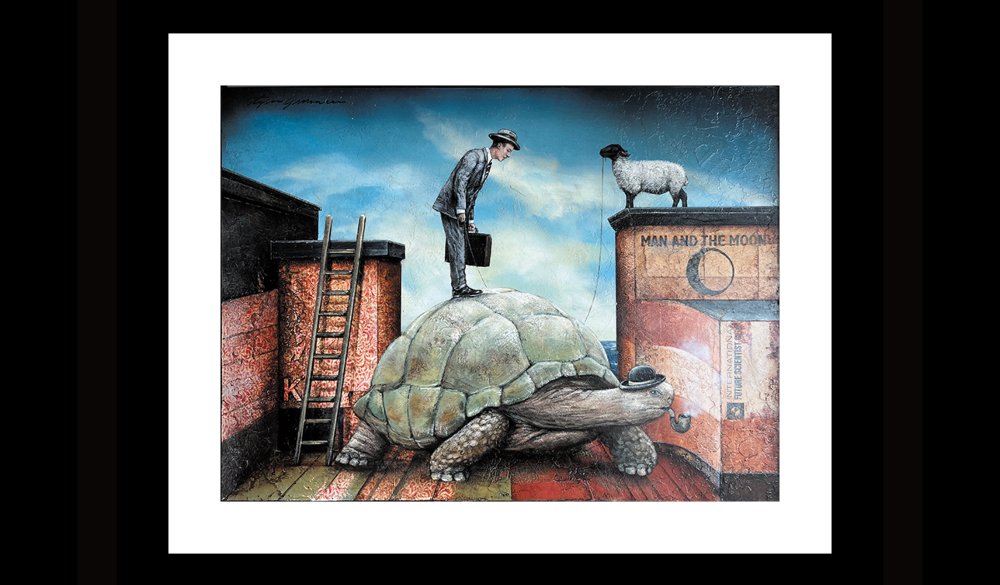

Once I had one trippy tortoise painting, of course I had to have another. So when I saw a painting by Tyson Grumm, who does these fun and whimsical Dr. Doolittle/Salvador Dali surrealist paintings involving animals, of a tortoise and a man in a suit, and sheep, at Patricia Rovzar Gallery (which also represents Talbot and Siems), I understood. And acquired.

On a recent trip to the Oregon coast, I was in a Manzanita restaurant ordering takeout when I noticed a small print of a Rt. 26 road sign fronting a landscape of beach grass lit by a setting sun. Technically, it wasn’t anything special, but it captured what I love about the Oregon coast, and it was only $50. I bought it and hung it in my bathroom. Unlike black velvet Jesus it doesn’t judge me when I pee.

This is what I mean when I say I seek out art that speaks to me personally. Most of it doesn’t. There’s plenty of great art available in Seattle that doesn’t work for me, whose essential nature seems opaque or inaccessible. Connoisseurship is nothing if not intensely subjective.

If you’re even vaguely interested, make the rounds of the local galleries. There are lots of them, representing all sorts of different local, regional, and national artists. Take advantage of Pioneer Square’s First Thursday art walk—yes, duh, it’s on the first Thursday of every month—in which dozens of galleries and other venues downtown participate. Just look at first; take your time. Wait until you come across work that seems personally meaningful, that you understand on a different level, at a deeper depth.

While work from established artists can be pricey, local galleries often highlight the works of younger and up-and-coming artists at lower price points. And, ahem, size matters: smaller paintings or other works are often surprisingly affordable.

If you look, you’ll find art everywhere, at every price point. As former Stranger art critic Jen Graves wrote back in 2012, in her version of this “buy art, goddammit” piece, “the world is jammed with 99 percent art.” You should own some of it. Believe your Uncle Sandeep when he tells you you won’t regret it.

I do regret that I never got a chance to tell Charles Rhyne how much he impacted my life. He passed away ten years ago, right about the time I (re-)started collecting art, so too late now. I’d have been shocked if he’d remembered me, anyway. But I have only to look at the walls of my home to see that he did impact me profoundly. My wife can laugh all she wants; I like collecting art. I’m not going to stop. And yeah, despite my best efforts, I know who John Constable is.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

My late friend Alex loved art as much as you do; he was never happier than when buying art. When he died, he left me with many of his crazy forays into collecting. That explains why my home is filled with odd works of art, including a manikin covered mosaic-like in mirrored tiles that reflect sunlight, bejeweling the hallway where it stands. He dubbed this piece of kitsch “St. Jean” in my honor. In its favor the piece is equipped with a U.S. and state flags and an indigenous spirit pole. Artist unknown.

The kitsch St. Jean sounds awesome! Now I want to see a pic.