A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them,” By Seattle author Timothy Egan (Viking, $30, on sale April 4), is the engrossing true story of one D.C. Stephenson, a “drunk and a fraud,” bootlegger, blackmailer, and sex predator, who grew the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana to the point where it ran the state from county courthouse to the capital. The latest book by Timothy Egan is both a Gothic tale of the 1920s, and distant mirror for viewing America today.

“I am the law in Indiana,” Stephenson declared. He aimed to be the law of the land. As author Egan writes, “Several hundred thousand Hoosiers had pledged fealty to and were effectively governed by a drunk and a dictator. He was not a man of God but a fraud. He was no protector of women’s virtue, but a violent predator.”

At its deeper level, this book is a narrative on nativism, the recurring “fear of others that courses through our country,” Egan said in conversation this week. “It is a theme that runs through era after era. To understand the 2020s, you need look at the 1920s.”

The original, post-Civil War Ku Klux Klan, celebrated on screen in “The Birth of the Nation,” was a Deep South terrorist organization that deployed fear to roll back rights of newly freed slaves. It was crushed by President Ulysses S. Grant.

The “Roaring 20s” Klan carried forward the attack on blacks – then migrating in great numbers to the north — but expanded its list of enemies to include Jews and Catholics and immigrants. At high water, the Klan claimed 6 million members across America, included 75 House members in Washington, D.C., plus four governors as sworn Klansmen. Its greatest power was in Indiana, the “most Southern of Northern states,” but other strongholds included Colorado and Oregon in the West. In Oregon, the Klan tried to outlaw Catholic schools.

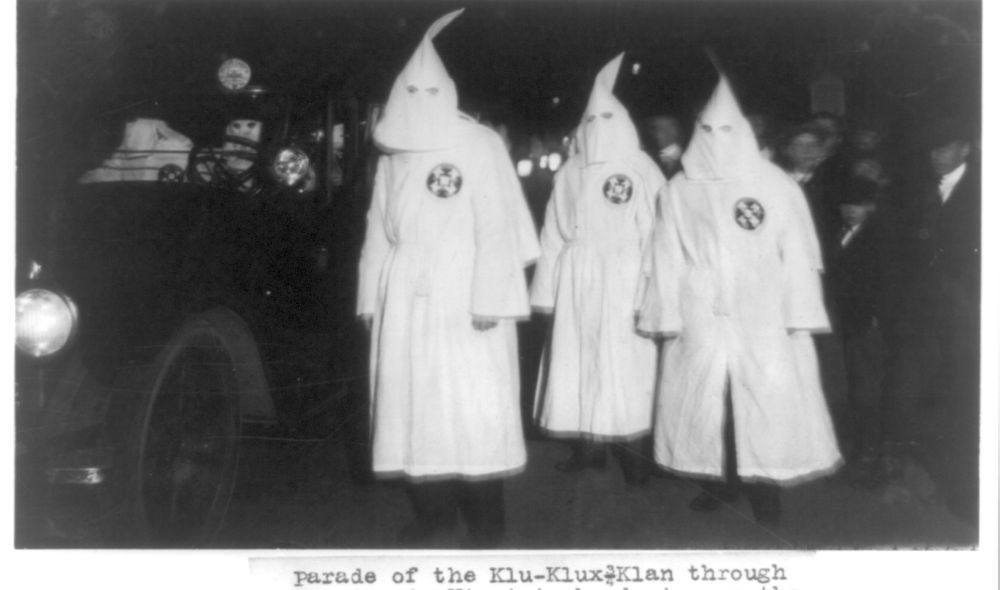

The Klansmen seen on screen in recent years, in movies like “Mississippi Burning,” are low life characters. The Indiana Klan was main street America. By night, the Klan bombed homes, set fires, and ran its enemies out of town. By day, as Egan writes: “They were people who held their communities together, bankers and merchants, lawyers and doctors, coaches and teachers, servants of God and shapers of opinion. Their wives belonged to the Klan’s women’s auxiliary, and their masked children marched in parades under the banner of Ku Klux Kiddies.”

Indiana was overwhelmingly white, Protestant, and native born. Yet what gripped Hoosiers, Egan said this week, was a fear that “change was coming to them — it’s at the doorstep.” It is a recurring theme, the fear the white race would be “mongrelized” and the country overrun with newcomers. Sound familiar? Tune in Fox News and hear Tucker Carlson talk about “replacement theory,” that immigrants are being ushered in to dilute power of our country’s white majority.

What else embodied the threat a century ago? Egan quotes H.L. Mencken’s famous remark on Puritanism, “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” The Klan stood for Prohibition, although Stephenson was a drunk. Banning demon rum was “part of a crusade against the meeting places and social rituals of immigrants.” (Egan cites Churchill’s description of Prohibition as “an affront to the whole history of mankind.”) The Klan didn’t like jazz, or the “Roaring 20s.”

The power of A Fever in the Heartland is in the story it has to tell. It reads like a thriller. Stephenson builds his movement, dominates his state as Grand Dragon of the Realm of Indiana, and dreams the Klan will sweep the country. A few courageous voices, an editor and a Catholic attorney, seek to expose its growing power. About the only overt resistance, for a time, came from University of Notre Dame students who pelted Klansmen with potatoes on the streets of South Bend.

The Grand Dragon’s undoing was a young woman named Madge Oberholtzer, employed by Indiana’s Department of Public Instruction. She is kidnapped by Stephenson, taken to a town near the Illinois border, and raped. She swallows bichloride of mercury, is left largely untreated, and takes nearly a month to die.

Madge delivers a deathbed testament. While Stephenson could claim to be the law — cops and prosecutors across the state were secret Klan members — he faced a gutsy Marion County Prosecutor. In Egan’s words, “Will Remy was a short man with a face so smooth it looked as if it was years from meeting its first razor blade. He could pass for a boy of 17 with prominent ears and slicked-back hair.”

Stephenson was convicted of second-degree murder. Will Remy and Madge Oberholtzer are the heroes of Heartland. Or as Egan puts it, “It took one person beyond the grave to bring him down.” Egan has a keen eye for telling detail and scene-setting drama. An example is the vivid account of Stephenson’s trial, its atmospherics, and the Grand Dragon’s pampered incarceration.

In wake of the trial and conviction, support for the Klan seemed to pop like a soap bubble. The Klan’s hold on Indiana receded. The movement began to unravel. Its leaders turned on each other, fought over the spoils. Crowds dwindled along with the hood count at parades.

Historians have treated scandals as the Klan’s death blow. Egan adds a different explanation: “The Klan disintegrated because it got what it wanted.” Jim Crow was locked in place, and segregation installed the North as well as South. Meanwhile black Americans migrated to northern cities, where redlining was used to keep them “in their place.”

Then, in 1924, Congress overwhelmingly passed the National Origins Act. The law set quotas based on America’s 1890 Census, taken before large numbers of Italians, southern Europeans, Polish Catholics, and Jewish refugees started to cross the Atlantic. By a law with bipartisan support, “America would be replenished with people who looked like the ethnic face of Indiana – a blueprint for a bloodstream,” writes Egan.

“In 1921, nearly a quarter million Italians had fled their country for the United States. By 1925, that number fell by 90 percent. About 200,000 Russian Jews arrived on American shores in 1921. A year after passage of the Immigration Act, only 7,000 were let into the country. Greeks went from 46,000 in one year to a few hundred. Left behind in Poland were 3.5 million Jews who would be targeted with mass execution in little more than a decade.”

Among those who sought entry, which was denied due to restrictions on Jews, was the family of Anne Frank. It would take more than 40 years, until 1965, for the odious Origins Act to be scrapped. Fifty-one years after that, however, America elected Trump as President whose campaign was fueled by attacks on immigration and immigrants. The “open border” is again a resonant theme in American politics.

The 1920s constitutes a high tide, but movements to demonize and exclude have swelled from Know-Nothings of the 1840s to the present day. Fear of a diverse, inclusive America is again a resonating force in our national life. It is manifested in hostility to history, suspicion of science, intolerance of lifestyles, even resistance to vaccination against a plague that has killed 1.1 million Americans. Legislatures in the heartland are again passing wacko laws aimed at minorities.

A Fever in the Heartland is one helluva book. It tells an absorbing story, with reporting that is both intimate and sweeping, and features a compelling cast of characters. The book is also a teaching instrument, exposing the darker side of the American dream .

The publication date is April 4 when Egan, the former New York Times man in Seattle, will take the stage at Town Hall Seattle.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for this insightful review; Tim Egan is the man to write this story of the KKK–which we as Americans can never forget. I’ll be in the Town Hall audience. Can’t wait to read it.

I have some family history in this as my parents came of age in 1920’s rural Indiana. They told stories of their older siblings running blockades of roads into town which had been set up by the KKK.

Another point I would like to make is that the youthful supporters of Lincoln in the 1860 election referred to themselves as the “Wide Awakes”. This from the book “Lincoln on the Verge”, by Ted Widmer. Highly recommended reading ( as are all Timothy Egan books!)..

“distant mirror for viewing America today”

Not distant enough.

Living in Indiana for almost 66 years gives me a better perspective of Midwest culture than some fella living in the liberal idiocy of Seattle. I knew the review was biased because of a few self centered comments describing his take on the books format but the remark about wacko laws from the Midwest definitely pushed me to this comment. The borders need to be controlled, the Democrats have always tried to pad the elections with fraudulent votes including illegal immigrants and criminals. Biden won the election illegally and I wish the proof would be totally exposed as it should be before I die. Just because we the people in Indiana are still patriotic and believe in the Constitution, creating laws that protect the rights of the citizens, looking for ways to secure the future of our country, doesn’t mean that we’re insensitive to public opinion. We care about our citizens which is something that the wacko liberals of the northwest have definitely forgotten to do. I would likely read the book because of the local history but definitely not because some liberal minded journalist wants me to jump on his bandwagon of hate and violence.

Thank you for your very fine parody of conservative talking points.

Thank you, Joel, for this comprehensive and provocative review. Not surprising that Tim gets to the roots of the issue. I am a Tim Egan fan and your review reads like he doesn’t disappoint for readers who want to be enlightened.

Dorothy, I’ve also, been a longtime Tim Egan fan especially since “The Worst Hard Time”. He gave a talk (at a Town Hall, I think?) when that book had just been nominated for the National Book Award. I mentioned to him during the signing. He laughed , said he didn’t have a prayer of winning it. And as you know, he won the award. Then and now, he seemed a genuinely humble and kind man and an enormously gifted writer. He wrote with great compassion and brilliance about that little-known chapter in American history. (Unknown to me, anyway!) Nobody who has really read his book of his could possibly say that he spreads hate, he doesn’t, he just doesn’t.

I no nothing about Indiana but I read a article that said Plainfield Indiana is the WORST place in America for non whites to live. I will be purchasing the book.

And yes, I’m deeply proud that he is a Northwest man and a graduate of the UW School of Journalism!

Ohio had the second-largest KKK enrollments in the early 1920s. My grandfather was the Akron YMCA Secretary, known for his Americanization of Eastern European immigrants for whom the burgeoning auto tire industry hungered as cheap wage employees. Grandpa Waller was also chair of the Akron school board. The Klan targeted the rubber companies — Goodyear, Goodrich, Firestone and the rest — and forced them to withdraw support for the Y. In the November elections of’23, Klansmen won a majority of the school board. They subsequently forced Waller’s resignation.

In ’23, my then twelve-year-old father had watched a cross burned on his front yard. He was ever thereafter, in both industry and public service, a scourge of the intolerant.

Here’s an excerpt from the Egan book, as it appears in a Washington Post column: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/04/03/kkk-midwest-jan6-indiana/