Last March, on the 80th anniversary of the internment of the Japanese Americans on the West Coast, the Seattle Times ran a mea culpa story. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, wrote Times columnist Naomi Ishikawa, “the U.S. media’s anti-Japanese fear mongering, racism, and war hysteria created a rationale for the suspension of civil rights that was accepted by the public.”

The most infamous newspaper to do this was the Los Angeles Times. “In the Seattle Times,” Ishikawa wrote, “news and opinion coverage during the removal of Japanese Americans might not have been as explicit, but it followed similar patterns.” Ishikawa points in particular to the use of the word “Japs” to label Japanese Americans and the military forces of Japan, which implies, she wrote, that “ancestry determines identity.”

I’ve read much of the Times’s coverage from 1941 and 1942, and Ishikawa is right about that. But as a former member of the Times editorial board many decades later I bristle at the blanket denunciation-in-hindsight. Yes, the Seattle Times could have done better. But to hold up as an ideal the Bainbridge Island Review, the small weekly that famously defended the Japanese Americans, is to imagine the impossible.

Back in the 1960s, I learned about the internment in high school. I asked my parents about it. “How did all that happen?” They said, “You had to be there.” I have heard this brush-off many times. I understood it better when I lived and worked during the national angst after September 11, 2001. There are times when America demands unity, and to hold out is almost impossible. The atmosphere early in 1942 was like that.

Racism was part of the problem. Racial animus was stronger in the 1940s than it is today, though Washington was never Mississippi. Our public schools were not segregated by law, nor did we have a law against interracial marriages. The Japanese Americans sent their kids to the public schools and to the University of Washington. They ate in the same restaurants and shopped in the same stores.

True, federal law had stopped immigration from Asia, and foreign-born Asians here could not become citizens. Under Washington law, only their U.S.-born children could own land. Still, the foreign-born could farm it, and by 1941, Japanese-American farmers were growing most of Seattle’s fresh vegetables in the Green River Valley, in Bellevue, and on Bainbridge Island. Japanese Americans were excluded from some neighborhoods by private racial covenants, but they had built their own businesses and real estate holdings.

Besides racism, the other part of the story was the war itself — Americans’ anger at the “sneak attack” and their fear of an attack here. A week after Pearl Harbor, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox said that an important factor in Pearl Harbor had been the acts of Japanese American “fifth columnists.” Knox had gone to Hawaii to make a report on the damage, and people had told him that. It wasn’t true, but he repeated it, and people believed it.

Japanese Americans here insisted they posed no risk to national security. James Y. Sakamoto, editor of the Japanese American Courier, told the Seattle Times that the Nisei (American-born children of Japanese immigrants) were “unswervingly loyal to the United States.” That was true, particularly of those educated here. (It was less so of the smaller group of Nisei who had been educated in Japan.) When Sakamoto said that the older generation, born in Japan, “have spent half their lives in the United States” and they were not going to be a problem, that was also believable for those who knew them.

On December 23, 1941, Sakamoto told a group of 1,300 Japanese-Americans that the Japanese American Citizens’ League was willing “to protect the country and ourselves by reporting any un-American activity to the proper authorities.” He was offering to inform on his own people.

The Times quoted Sakamoto and others many times, and respectfully, and at first, it was on their side. On January 8, 1942, the Times accepted the Nisei declarations of loyalty. It said, “There must be no incitement of groundless suspicion; no interruption of friendliness for any cause short of positive proof.”

However, many Americans wanted to put the burden of proof on the Japanese Americans. The demand that an entire class of people prove that it posed no risk was impossible to satisfy, but it led to an obvious conclusion. At the end of January, Leland Ford, Republican of California, called for the removal of all ethnic Japanese from the West Coast. Ford was not a powerful member of Congress, but he was the first to stand in the spotlight and say it.

In an editorial on February 1, 1942, the Seattle Times defended Japanese Americans: “The question of what to do about resident Japanese is not one to be lightly weighed or dismissed with a hand toward concentration camps. Most of these people have been among us many years: self-supporting, law-abiding members of our several communities. Thousands of them are American-born and, if of age, are American citizens.”

Here was the time to stand on the hard rock of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution: that no person “shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” But citizens’ rights were not the focus of the public argument in 1942. The focus was on national security — whether allowing the Japanese Americans to remain free was safe for everyone else. Even the principal argument of the Japanese American Citizens League wasn’t that the government had no right to take them away. It was that there was no need to take them away.

And who would decide what was needed?

The Seattle Times concluded: “We believe the problem can and will be worked out by the proper authorities; and this without need of uninformed gossip and biased opinion. We must rely upon official vigilance until conclusions are reached.”

Trust the government – that became the Times’ position. After all, ours was a democratic government, responsible to the people. But the people — and not only whites — were angry and fearful, and not inclined to accept any risks.

The newspapers were full of fearful stories. From overseas came the story of the desperate fight of Douglas MacArthur’s men in the Philippines, and the first stories of Japanese brutality there. Japan’s forces were sweeping down the Malay Peninsula toward British-ruled Singapore. The Times also carried what-if references to a Japanese invasion here, including, on March 7, 1942, a page-one map of the West Coast showing an imaginary invasion force sweeping inland from Grays Harbor to Portland and Seattle.

Local stories heightened the fear. The Times ran the story of two Nisei businessmen indicted for an attempt to sell three large steel storage tanks to a buyer in Japanese-occupied China. The government had blocked the sale and the tanks were never sent, but federal agents said the storage tanks had really been bound for Japan. The story said the tanks were capacious enough to fuel 12,000 planes to fly from Japan to Seattle and back — a scary thought. The story did not say whether Japan’s planes could fly that far.

On February 5, 1942, the Times ran the story of an FBI raid on the homes of non-citizen Japanese on Bainbridge Island, searching for cameras, maps, short-wave radios, shotguns, rifles, and even antique Japanese swords. The big seizure was of dynamite. That sounded ominous, though the story noted that the Japanese had been using the dynamite to clear tree stumps on their farms.

On March 8, 1942, came the story that the FBI had seized from a Japanese man 100 lapel pins with the Nazi swastika. How was a cigar box of swastika pins a danger to national security? No one would dare to wear such a pin in public. “It was pointed out that the Japs possibly intended to use the swastika pins to identify themselves as fifth columnists in event the Japanese army invaded Seattle,” the article speculated.

A notably nasty voice in the Times was that of Henry McLemore. He wasn’t a Timesman, but an East Coast columnist syndicated by Hearst. Originally McLemore had been a sports writer. His schtick was to express what the average man was thinking, in language that was saucy, simple and blunt.

McLemore traveled to Los Angeles in January 1942, and was shocked at what he saw. “You walk up and down the streets and you bump into Japanese in every block,” he fumed. “They take the parking stations. They get ahead of you in the stamp line at the post office. They have their share of seats on the bus and streetcar lines.”

He went on: “I know this is the melting pot of the world and all men are created equal and there must be no such thing as race or creed hatred, but do those things go on when a country is fighting for its life?

“Not in my book,” he wrote, referring to the stories of fifth columnists in Hawaii and Manila. “I am for immediate removal of every Japanese on the West Coast to a point deep in the interior. I don’t mean a nice part of the interior, either. Herd ’em up, pack ’em off and give ’em the inside room in the badlands.”

This was not the Seattle Times’ opinion. But on January 30, 1942, the paper printed it. They wouldn’t have, any time in the past 50 years, but they did, then. The Times printed more of McLemore’s blasts at the Japanese.

And public sentiment was moving McLemore’s way. The Times of February 24, 1942, reported that four mothers in West Seattle were circulating a petition to fire 23 Japanese American clerks in Seattle public schools. The petition declared that it was dangerous to have Japanese clerks taking emergency calls. The next day, the clerks quietly resigned. Declared the Seattle School Board, “The fine spirit shown by the girls in offering their resignations as a means of eliminating controversy which might be a divisive issue in the community testifies to their high regard for their responsibility as American citizens.” At about this time, the Japanese American “red caps” at the King Street and Union stations were hounded out of their jobs.

By the end of February 1942, West Coast politicians had lined up behind Representative Ford in support of internment. In California, this included Earl Warren, the Republican state attorney general who would later write the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

Later, when the internment was challenged at that court, this state’s justice on the Court, Roosevelt appointee William O. Douglas, sided twice with the government against the Japanese Americans. Warren Magnuson, then Seattle’s Democratic congressman, was serving in the Navy, and took no part in the public debate.

In early March 1942, a Congressional hearing was held in Seattle on what the Times called a “general enemy-alien evacuation,” which included citizens. At that hearing, Seattle Mayor Earl Millikin said, “Seattle residents overwhelmingly desire removal of Japanese, particularly aliens, but the feeling carries over to native Japanese as well… The Japanese American Citizens League has been very helpful, but they won’t ‘squeal’ on their own people.”

Governor Arthur B. Langlie, Republican, said Washington said the people wanted “all enemy aliens evacuated immediately.”

The Seattle Chamber of Commerce declared its neutrality — unlike the Los Angeles Chamber, which had come out for internment. Like the Times, the Chamber was saying to the government: You decide.

A few individuals spoke up for the Japanese Americans. One was Jesse F. Steiner, sociology professor at the University of Washington. Steiner, who had lived in Japan, said “I feel that the prejudice in Washington is much less than in California, and that prior to the trouble in the Pacific, they [the Japanese Americans] were considered an asset.” Esther Boyd of Wapato said, “We’ve heard some of the whites say, ‘Get rid of the Japs and we can have more land.’ But I have found and believe that the Japanese in our area are loyal Americans.”

At the time of these hearings, the American Civil Liberties Union announced its opposition to the internment, but it was too late. The Seattle Times had put its trust in the government. On March 5, 1942, the Times accused the ACLU of “making mischief” by “trying to thrust itself into the question of what should be done about alien enemy residents of Pacific Coast states and American citizens who are offsprings of such aliens.”

The debate was over. You could hear that in the words — the increasing use of “alien” and the insidious spread of “Jap,” first in headlines, and then in any story with a negative tone. Today’s term, “Japanese Americans,” was not used.

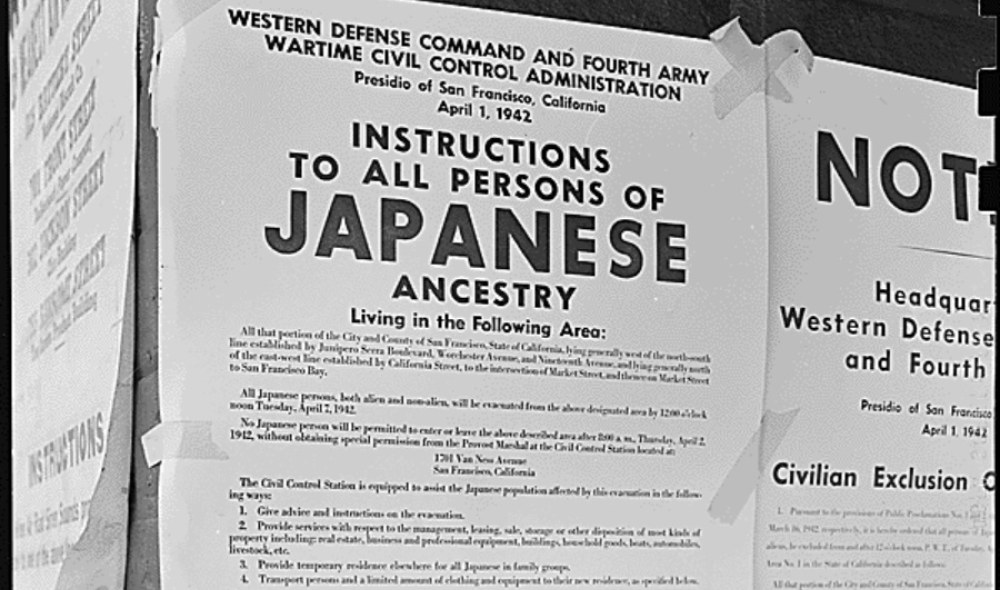

The legal basis for internment was Executive Order 9066, signed by our Democratic president, Franklin Roosevelt, on February 15, 1942. His attorney general, Francis Biddle, opposed internment; and the director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, said it wasn’t needed. But it was Roosevelt’s decision, and officials fell in line. Under his executive order, 122,000 West Coast Japanese were interned, including nearly 70,000 U.S. citizens, without any pretense of hearings or due process of law. (Several thousand Germans and Italians were interned, too, but only the non-citizens, and only after hearings.)

“Internment” was not a word used until the very end. The Japanese were to be “moved,” “relocated” or “evacuated.” And the Japanese Americans didn’t stage protest demonstrations, perhaps thinking You can prove your loyalty by going along and not complaining.

Japanese institutions were soon shut down. On February 20, 1942, the Times reported that the federal Treasury Department had closed a red-brick Buddhist temple at 1427 Main Street because its non-citizen owners lacked a federal license. On March 14, 1942, the Treasury Department closed the foreign-owned North American Times, a Japanese paper edited by Budd Fukei (who years later was my colleague at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer).The paper had loyally supported the United States.

The Seattle Times covered the removal of the 227 Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island on March 24 and 25, 1942. “There was no apparent antagonism to the evacuation order,” the Times said. “May Katayama, high-school junior, said, ‘I know it has to be done. I’m not bitter but I hate to leave the island. I was born here.’ ”

The Times quoted a farmer, T. Hayashida, who was spreading fertilizer among his strawberry plants. “‘They tell you one thing and then they tell you another, and a fellow doesn’t know what he’s going to do,” he said. “But if the country thinks it is best for us to move, why, that’s all right.”

In her story last year, Naomi Ishisaka complained that every Japanese American quoted in the Times’ stories of the Bainbridge evacuation “was depicted as cheerfully resigned to their fate and even proud to do their part.” “Cheerful” is an overstatement; “proud” is accurate. They were putting a good face on it.

Clearly the Times could have done better — but how much better? The Bainbridge Island Review, a weekly paper that had been bought the previous year by Walt and Milly Woodward, defended the Japanese Americans. The Seattle Times, owned by the Blethen family, was bigger and more powerful. It is tempting to think that it was the Times’ duty to have done the same.

After a career at the Times and Post-Intelligencer, it’s difficult for me to imagine such a thing. It took courage for the proprietor of a small business to stand athwart the flood tide of public opinion, and the Woodwards are rightly celebrated. But it was their paper, and they were free to risk it. The publisher of the Seattle Times didn’t have that freedom. The Times had hundreds of employees depending on it. It had union contracts, advertising contracts, and vendor contracts. It had bank loans to pay and taxes due. It had fiduciary duties to bondholders and to minority stockholders, which owned 49.5 percent of the company.

And who really was the publisher? One could imagine the company’s founder, “Colonel” Alden Blethen, putting up a fight. “Colonel” Blethen had fought Prohibition, which the people of Washington supported. But by 1942 the founder was long dead. His more conventional son, Clarence, had died in October 1941. At the time of the Japanese internment, the Times’ publisher was the company’s lawyer, Elmer E. Todd, the first non-Blethen to run the family’s paper. His job was to conserve the family’s assets, not risk them.

The internment of the Japanese Americans was not a good moment for the Seattle Times, or any other American daily newspaper. It was not the best moment for American democracy, either, or for the famous President whose head is on the dime. But the year 1942 was a lifetime ago. It was a different time, and one that may never occur again. People today need to know what happened, but we do not need to whip ourselves over it.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nicely done. I have always wondered since there are still Japanese-Americans alive today were interned at those camps as well as those who worked at them has the nation truly healed from that poor decision to intern Japanese-Americans? The fact that Japan has not apologized for their bombing of Pearl Harbor nor has the US apologized for bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki says something though both countries are considered allies today. There has been a price to pay for such thinking then and it’s still a work in progress today.

Thank you, Bruce Ramsay, for his detailed account of public sentiment in Seattle leading up to the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Historical context does matter. My father, a U.S. Navy officer during the war, never defended the internment, but he admonished this smug child of the ’60s to understand the fear that pervaded the U.S. after Pearl Harbor.

In our hometown of Hood River, OR, a petition in favor of removing the Japanese was circulated, and more than fear motivated people to sign; there was also the scent of economic opportunity. A buyer’s market was created when land was left untended or at least less well-tended during the internment. Certain farmers took advantage.

All this came with a racial divide that I better understood after interviewing Hood River residents about their memories of the ’30s and ’40s: Two of my subjects, both white women, could recall a time when there was an implicit racial divide and, in particular, interracial dating was taboo. In such an environment, suspicion bred easily.

Hood River made the history books for some of its misguided actions against its Japanese residents, and the community has since made public atonement, most recently by renaming the main highway through the valley in honor of Japanese-Americans who served in the U.S. military during World War II. This is hardly equivalent to the dislocation endured by those were uprooted from their homes. But it’s a worthy reminder of how many Japanese-Americans fought to defend this country even while their loved ones sat out the war behind barbed wire.

Very good story. My father, Fred Bergman, owned a luggage store at 2nd and Jackson. He had many Japanese friends who brought their possessions to store

in his basement. He was outspoken in denouncing the relocation. “They could do the same thing to Jews, “ he said.

Well done, Bruce. The Times should run your piece to balance their previous story. If I were still editing the Sunday Opinion section, I’d do that in a heartbeat. They are prone to “presentism” — judging past policies and decisions by today’s standards and values. It’s a lazy, shallow and intellectually dishonest approach that has more to do with virtue-signaling and self-aggrandizement than good journalism. But it’s unfortunately pervasive in the media today. Keep calling them out and holding them publicly accountable. Somebody’s got to do it! Kudos.

Please read Larry Matsuda’s response!

Jon Meacham has a good phrase for this kind of history: “reducing history to ammunition.”

This was valuable and compelling reading for historic context. Makes me wonder what’s happening to Ukrainian citizens still in Russia and vice versa.

Good piece reflecting the context of the time without making apologies for it. However, I don’t think it is accurate to say the Woodwards “stood athwart the flood tide of public opinion” in their support of Bainbridge Island’s Japanese Americans. As Ramsey notes, 227 island residents, a large segment of the island’s population in those days, were forced to leave. They were people most islanders knew and liked, as evidenced by the connections the community, through The Bainbridge Review’s pages, throughout the internment. Acknowledging this doesn’t diminish the Woodwards’ courage, but I think it more fully explains why their decision was different than the Seattle newspapers.

What mattered to the Times, as Bruce tells it, was “… The publisher of the Seattle Times didn’t have that freedom. The Times had hundreds of employees depending on it. It had union contracts, advertising contracts, and vendor contracts. It had bank loans to pay and taxes due. It had fiduciary duties to bondholders and to minority stockholders, which owned 49.5 percent of the company.”

No, Bruce. The Times should have done better. Leading the debate with facts, not allowing community misplaced fear to hold sway. Still holds true.

Bruce Ramsey’s January 16th 2023 article, “Understanding the Times: How the Japanese Internment was Reported”

The article was a failed attempt to justify and discount an undeniable and Un-American injustice. In the title, the pun of the “Times” is a cute way to imply that we need to understand the times as well as the Seattle Times as if he were the sage dispensing wisdom and truth.

It is clear, however, Ishikawa struck a guilty nerve of Ramsey’s regarding the Japanese “internment” reporting by the Times. The word “Internment” was one of a number of euphemisms used for forced incarceration camps or race based concentration camps most of which were located in inhospitable areas and deserts. After all what do you call a camp surrounded by barbed wire with guard towers where they would shoot you (and they did) if they thought you were trying to escape? It wasn’t a summer camp in the Catskills with dirty dancing and art lessons.

Approximately 120,000 Japanese were forced from their homes for years. Two thirds were citizens and 40-50% children/adolescents. Americans with 1/16th Japanese heritage were among those rounded up. This constituted the group that the government said was a security risk. German and Italian American families did not fall into the same category as the Japanese. After all, General Dwight Eisenhower (German) and Joe DiMaggio, “The Yankee Clipper”, (Italian) and their families were above reproach. If Japanese posed a real threat, why weren’t Hawaiian Japanese taken en masse? The media and newspapers (except for one) had their thumbs on the scale to support the forced incarceration.

In addition, the injustice was supported by the Supreme Court when it ruled against Hirabayshi, Korematsu, and Yasui in separate cases. Those rulings still stand on the books today. Not only did the courts fail to maintain fundamental rights –life liberty, habeas corpus, etc. but others joined in including chambers of commerce, fraternal clubs, “Ban the Japs” groups, granges, many politicians, newspapers, and media. It was a free for all where Chinese had to wear “I am Chinese” buttons to dodge the hate.

So why did this happen? Presidents Reagan, Bush Sr. and Clinton stated the causes of the incarceration in their letters of apology to eligible Japanese Americans. They identified the causes as: Race discrimination, wartime hysteria, and failed leadership. These forces are still alive today. Racial prejudice is evidenced by Anti-Asian Hate crimes related to COVID and Black Lives Matter. Wartime hysteria was called propaganda during WWII and it is now called fake news, alternate facts or lies. Failed leadership is evident today by the number of state/national initiatives promoted by some politicians to curtail civil and voter rights.

The threats continue and as Mark Twain said, “History does not repeat itself but it rhymes” so the lessons must not be forgotten even though Ramsey points out that it was many years ago. Following that line of thought about what his parents said about the times— which was in effect that you needed to be there to understand. If Mr. Ramsey were there and he had yellow skin, slant eyes, and a Japanese surname that would add some level of understanding.

But another perspective comes from a presentation I made at the Minidoka, Idaho (WRA concentration camp) pilgrimage. After I spoke one middle aged man stood up and said he was raped as a child. He went on to explain that the forced incarceration was a rape of an entire community based on race. After being raped by our trusted uncle (Sam) we behaved like rape victims. We were in denial, tried to prove we were worthy, silent, angry, depressed, suicidal, more patriotic, and damaged. These effects extended beyond the victims to descendents as well in terms of fear, guilt, and shame to bear.

Yes, Mr. Ramsey from the luxury of your entitled life, you need to understand the times—then and now and how injustice can damage and span generations of those who were betrayed and imprisoned by the government because of their race. What Ishisaka said was nothing in comparison.

Sincerely,

Lawrence Matsuda

Former resident of the Minidoka Idaho WRA (Concentration Camp)—

Block 26 Barrack 2 where my mother, father, brother, grandmothers, grandfathers,

uncles, cousins, and aunts were incarcerated for over three years.

Thank you

Full disclosure – Lawrence Matsuda is a long time friend and activist colleague. I welcome his compelling narrative of his personal experience of the interment and media coverage then and in retrospect.

There are at least a couple ways to respond to historical injustice. One is to do what the Times tried to do in its evaluation of its racist reporting and editorializing from 1942: be honest. The other is to do what Bruce Ramsey tried to do in this disappointing rejoinder: be defensive. We see this all over America today, most censoriously in FL, where Gov. Ron DeSantis is trying to “protect” that state’s white kids from a sober analysis of our ugly history.

As Lawrence Matsuda notes (above), German and Italian-Americans were not rounded up as a class and sent to camps. Why? Because, unlike Japanese-Americans, they had become “white;” they had been “mainstreamed.” Let’s quit trying to justify or “explain” this. Let’s be honest.