In the musical Hamilton, a catchy song repeats and then changes. Initially we hear it when George Washington favors Alexander Hamilton for the position of Secretary of the Treasury. The little chorus sings, “It must be nice, it must be ni-ice to have Washington on your side” because Hamilton has gotten the job. Later, during the contentious election of 1800, Hamilton works behind the scenes to elect Jefferson over Burr, (as he preferred a man of “wrong principles” over a man of no principles,) and the song reprises, with the chorus singing now, “It must be nice, it must be ni-ice to have Hamilton on your side.” And Jefferson wins.

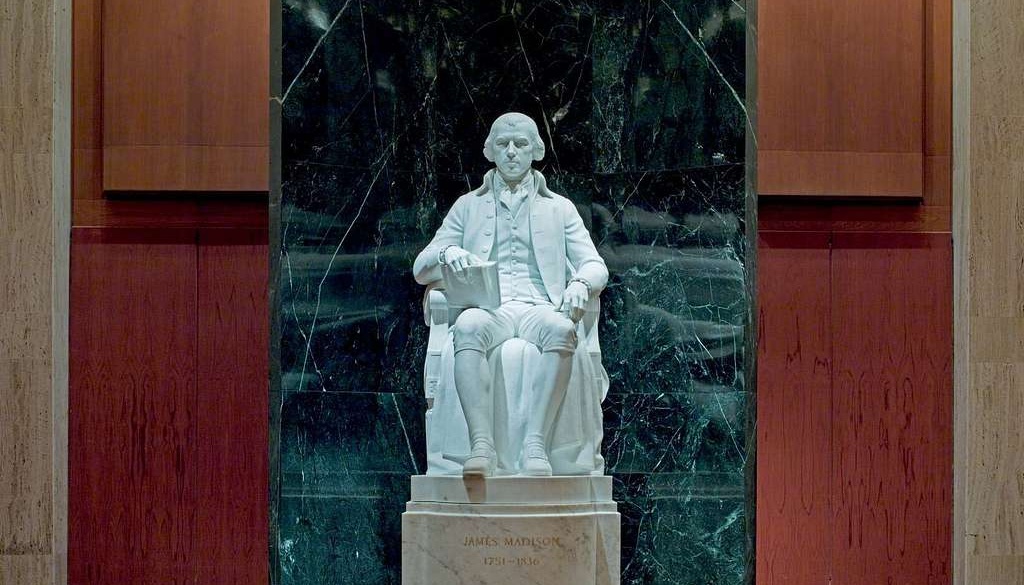

The bizarre defects of our electoral system have been laid bare (again) by recent elections, and the method of choosing the executive is (again) under scrutiny. How can we assure that the winner of the popular vote is the victor? Should we even care about that? Surely in a democracy the people should choose the national leader. And while it is indeed nice to have the Father of our Country and of the Treasury system on your side, in these questions, it’s the Father of our Constitution you want—it would be nice, it would be ni-ice to have James Madison on your side.

Before proceeding, we need to do a vocab pop quiz. Ready?

- What does the word “majority” mean?

- What does the word “plurality” mean?

Think about it for a minute. If you are like me, you grew up amongst people who, when discussing some minor choice like what TV show to watch, would often fall back on the phrase, “Majority rules!” and smugly grab the remote. I heard it a lot, in many different contexts, as I’m sure you did too. Now I ask you, did anyone ever yell out: “Plurality rules!”?

I suspect not.

Okay, time’s up! Here is the answer to our pop quiz. If you answered “a ‘majority’ is the thing–candidate, TV show, ice cream type–that gets the most votes,” if that was what you were thinking, you receive zero credit for your answer. But if you thought, “ ‘Majority’ is 50% plus one vote” then DING DING DING, go to the head of the class. Full credit.

On to question two. What is a plurality? ‘Plurality’ is the thing or person who received the most votes among several choices but did not clear the more-than-half majority bar.

If you answered correctly, stay at the head of the class. If you’d never really thought much (if at all) on the meaning of the word plurality, and did not know the answer, you don’t get any credit. But you can assuage yourself by thinking that pretty much no one else did either.

Quiz part 2:

3. Did Donald Trump win a majority in 2016 or a plurality? (Answer: Sorry. It was a trick question. He won neither a majority nor a plurality of the popular vote (46.9%), but he did win a majority in the Electoral college. )

4. Did Hillary Clinton win a majority in 2016? (No. She won a plurality—48.53% of the popular vote–but lost the Electoral College.)

5. Biden won the popular vote in 2020. Was it a majority or a plurality? (Answer: Majority, Biden won 51.33% to Trump’s 46.42%). He also won the Electoral College.

So how did neither candidate in 2016 manage a majority of the vote? Answer, because neither major candidate was terribly well-liked and there were many other candidates to choose from; the Green Party and Libertarian Party each won significant percentages. These candidates are sometimes referred to as a “spoilers,” as they “spoiled” the chances of either of the main party candidates winning a majority of the votes.

Okay. We are done with the quiz. Time for history class. Yay!!

During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, James Madison consistently expressed support for the chief executive to be “an immediate choice of the people.” Or in other words, elected by the popular vote. He argued this repeatedly. He was a man of principle—and stuck to this one even when he was aware it would undercut the advantages gained by the South in the infamous three fifths compromise.

While knowing that a direct election of the president would disadvantage the South, he stated on July 25, 1787 that “local considerations must give way to general principle.” As we are all too well aware, this principle was not shared by the majority of the Framers, who had a long hot summer hammering out the details of the Constitution, compromising over and over. One of their final compromises was the mechanism for electing the executive: the Electoral College, which was designed hastily and sketchily in the last days. But even here, one principle shone forth: the importance of majority support over plurality winners, witnessed by the desire for leaders who were consensus candidates.

It hasn’t exactly worked out that way. The system has given us a plurality winner for president rather than a majority winner in 19 of 59 elections. In other words, the majority of voters in those nineteen cases gave their support to some other candidate. Worse, in five elections, it was not even the plurality winner but the loser of the popular vote who was inaugurated. Madison would be disappointed.

You see, Madison and the other Framers of the Constitution liked majority rule. Our whole system is based on it, including the Electoral College– in which a candidate must win a majority rather than a mere plurality to get the presidency. The principle was so important that they built in a mechanism for what happened if no candidate won the majority of the Electoral College votes: the election would be decided by the House of Representatives. There too a majority would be needed. Perhaps naively, the Framers were presuming that it would be rare for the election to be decided by the Electoral College because, you see, there would always be a plethora of candidates. They anticipated that the Electors would, in effect, be a nominating body, and the House would choose from among the top five candidates. What the Framers did not expect was an emergence of a fierce two-party system with lots of little minor parties cavorting around on the outskirts of the system wreaking havoc.

They didn’t fret over the mechanism for choosing the executive too much at the end of that hot summer in Philadelphia because (bonus quiz question!) everyone knew who was going to be elected to serve as the first president and become known to generations of school children and candidates for citizenship as the Father of our Country: George Washington.

In the first two elections, that whole majority/plurality thing didn’t figure in at all—rather a different electioneering word: unanimous. Washington was elected unanimously. Twice. (Pretty much dispositive as to why it was nice to have Washington on your side.) But only two elections later, in 1800, the Electoral College was pretty much a disaster. That contentious election was spoiled by the rather odd decision to have the Electors cast two votes with the runner-up becoming vice president. (If you don’t instantly see why this was a bad idea, just pause for a moment and imagine Hillary Clinton as vice president under Trump. Or vice versa.) Most of you have heard by now how Burr and Jefferson tied that year in the Electoral College, 73 to 73—someone literally had not received the memo that he should be the single party member to cast one vote only—for Jefferson–and to abstain to cast the other. When Burr unexpectedly found himself tied with Jefferson, he discovered he rather liked the idea of being president, and refused to concede, which sent the election to the House, where it took 36 ballots before Jefferson finally prevailed with the majority of the votes.

Yeah, you knew that right? And here is another example proving how important the Framers felt the majority rule principle was. Did you know that for the first 35 ballots, Jefferson was actually the winner, but only the plurality winner. Since there were an even 16 states at the time, 9 were required to win. For those first 35 ballots, Jefferson actually received 8 votes to Burr’s 6. This was because Vermont and Maryland split evenly in their delegations and essentially abstained. For those 35 ballots, it was not an 8-8 tie, as I’d always assumed, it was a 8-6 plurality for Jefferson! Who knew? However, the Constitution mandated a majority winner. As anyone who has seen the musical Hamilton can tell you, Hamilton worked behind the scenes to get Jefferson (whom he hated) elected because he was “not so dangerous as Burr.” And on the 36th ballot in the House, Jefferson finally won. It was nice indeed to have Hamilton on your side.

Multiple lessons are learned here… one is that it was a terrible idea for each member of the Electoral College to have two votes, with the runner-up becoming vice-president; and the 12th amendment was expeditiously passed to require “distinct ballots,” one for president and one for vice-president. What didn’t change was the requirement that a majority of the Electoral College must decide the election, and if no majority was reached, rather than give the presidency to the man who won a mere plurality, the election would be decided by the House, where again a majority was needed. It was clear again how important a consensus candidate was. (I have to wonder, if the Framers had adopted a direct popular vote as advocated by Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson if they would have insisted on some mechanism to ensure a majority winner.) At this point in history—1800–a small ruckus was made to amend the system in favor of a direct election of the executive, but it died out, and Electoral College reform faded away for another day. For the next five elections, the majority candidate did indeed win. Jefferson for a second time with 72.79% of the popular vote; Madison 64.73%; Madison 50.37%; Monroe 68%; Monroe 80%. (Second bonus quiz question: What did these three men have in common with Washington? Yeah. You know. Slaves.)

Meanwhile, over the next two centuries, the Electoral College has been irritatingly difficult to rescind, even though Madison’s principles of Majority Rule and Direct Election by the People has grown stronger and stronger amongst nearly all Americans. A couple of creative solutions are gaining traction, one is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, and the other: Ranked-Choice Voting. Ranked-Choice Voting rests on the principle that candidates should be elected when they have majority support, rather than a plurality win. In RCV, voters rank their choices, 1-2-3-4 etc., and if no candidate receives a majority of votes in the first count, the last choice candidate is eliminated and the votes allocated to those voters’ second choice. The process is repeated until a candidate emerges with majority support. At least 50% plus one. (This can be done practically instantaneously now thanks to computers and is sometimes therefore referred to as “instant run-off.”)

The basic idea is that elected officials should govern from a position of broad-based support. This is what Madison advocated for. A plurality winner might be (and in fact in several notable elections has been) an extremist favored by a minority, when a majority of voters necessarily preferred someone else. Perhaps anybody else. In a multi-candidate race, listing only one choice can too easily result in no candidate achieving 50% of the vote. Remember the pesky minor candidates flashing in and out of our consciousness? They can often “spoil” the will of the majority by receiving just enough votes to keep the victor under 50% and “throw” the election to their least desired candidate. In our elections, the winner of the plurality is too often the victor. (In fact in four of the last eight presidential elections.) But who is to say that the majority would have preferred the runner-up candidate? RCV eliminates the dreaded spoiler candidates by allowing the second choice preferences of their voters to be considered. Then and only then can we be sure that the victor has majority support.

The point of this little history lesson is to remind everyone how important the concept of a consensus candidate was to the Framers. They did not like the idea of a man becoming president with minority support. If only they had thought of Ranked-Choice Voting!

But wait! One of them did!

Back to history. In 1824, things started breaking down for that Virginian lock on the presidency. In fact, with the collapse of the Federalist party, it looked like there would be four serious contenders, each claiming to be a Democratic-Republican—John Quincy Adams (Secretary of State), Henry Clay (Speaker of the House,) Andrew Jackson (Senator from Tennessee) & William Crawford (Treasury Secretary.) A pretty serious lineup, wouldn’t you say?

A prescient James Madison was worriedly watching from cozy retirement and was distressed that, with four strong candidates, no candidate would receive a majority of Electoral College votes. How might that be avoided? He had an idea: “that each Elector should give two votes, one naming his first choice, the other naming his next choice. If there be a majority for the first, he to be elected: if not, and a majority for the next, he to be elected” . After that, the election would be decided by the House of Representatives. Madison thought a consensus candidate so important he wanted to make this change in the Electoral College. Sounds like Ranked-Choice Voting to me!

Madison’s idea was only expressed privately in his letters to close associates; no changes were adopted for the election of 1824. The election was chaotic and, as anticipated, no candidate garnered a majority of votes. Jackson won the plurality with 41.4%, while Adams was the runner-up with 30.9%. Clay and Crawford trailed with 11.2% and 13%. For the second (and we hope the last) time the election was decided by the House: in Adams’ favor when Clay urged his supporters to back Adams. Which they did. Adams then appointed Clay Secretary of State. Was some bargain made? If so, was it corrupt? (For extra credit, write an essay. Defend or refute.) In any case, Jackson was pretty upset about it.

Until we can rise up in a strong voice and demand that the Electoral College be eliminated and the president of our democracy be elected by the people in a direct popular vote, we could at least adopt a system of Ranked-Choice Voting, which would help render a consensus candidate. Madison would surely agree. And yes, it’s rather nice, it sure is ni-ice to have Madison on our side.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Huge thumbs up for the suggestion of ranked-choice voting! If we had been using RCV since the founders were around, we would almost certainly have a much more vibrant democracy with many more voices and much less partisanship now.

Thanks for writing!

Very elegent writing, very clear history class.

You invokes me to think about the creation of this voting system and whether it is still well adapted to current society.

Appreciate this piece! Too often we hear, “The Founders blah blah blah” without acknowledging the Founders are indeed MANY people with MANY ideas, and some of them disagreed with the mechanics of how our government should be structured… and that today, we all need to be creative and keep pushing this stuff as we learn more, and not just pretend that every answer people came up with 300 years ago were perfect answers.