Our region’s most recently-created National Park Service property is a 1945-vinage building on the Columbia River, near the Vernita Bridge, which was first on line manufacturing plutonium for the World War II Manhattan Project. The B Reactor was the world’s first large scale nuclear reactor. It manufactured plutonium used in the Trinity blast in New Mexico, the first test of a nuclear weapon. Plutonium from B Reactor was used in the Nagasaki bombing on August 9, 1945.

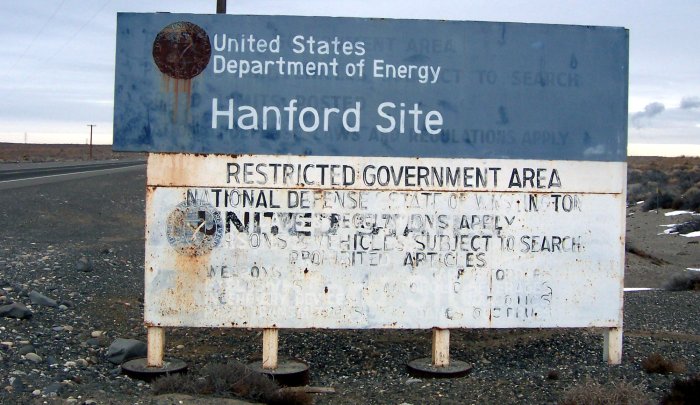

The 560-square mile Hanford Reservation manufactured plutonium for nuclear weapons for more than four decades. Its mishaps, and cleanup of the nation’s largest concentration of high-level nuclear waste, have been a major Northwest news story for 40 years.

“The Apocalypse Factory,” by Steve Olson (Norton, $27.95), tells the story of Hanford, its role in the $2 billion Manhattan Project, and its job as a Cold War bomb factor. The reservation would become a not-so-successful centerpiece in efforts to seek peaceful uses of atomic energy. Or, in Dwight Eisenhower’s syntax, “useful pieces of atomic energy.”

In Olson’s view, Hanford hasn’t received the attention – outside the Northwest – of Los Alamos in New Mexico, where scientists designed the bomb, or Oak Ridge in Tennessee, which produced uranium used in the Hiroshima bomb. Olson, who grew up in Othello, WA, is a sure-footed story teller and historian of the Northwest. A previous book, “Eruption: The Untold Story of Mt. St. Helen’s,” discoursed on topics from explosive properties of a stratovolcano to Weyerhaeuser’s role in setting restricted area boundaries.

Unlike other Hanford tomes, Olson offers a history free of ideological implosions. Creation of plutonium, by a team led by scientist Dr. Glenn Seaborg, is described in lucid terms that a layperson can follow. But the book’s strength is in describing creation of an enormous construction site and a permanent city (Richland) along the Columbia River.

Olson veers away from rivalries among the scientists, and appreciates those who did the grunt work of getting reactors to work. Writes he:

“Scientists and engineers provided many a solution, but many came from the machinists, pipefitters, millwrights, carpenters, plumbers and other craftworkers who built and ran Hanford. Scientists and engineers get much of the credit for innovations in industry and society, but many of those innovations actually have humbler origins.”

Olson leaves Hanford to explore debate over whether and how to use the bomb. Leading scientists wanted a demonstration blast. The boss of the Manhattan Project, Gen. Leslie Groves, campaigned for destruction of not one, but two Japanese cities. In a key confrontation, Groves wants to hit Kyoto, but destruction of Japan’s famous culture and education center is vetoes by Secretary of War Henry Stimson. “Groves has just brought me his report on the proposed targets,” he tells Gen. George C. Marshall. “I don’t like it. I don’t like the use of Kyoto.”

Stimson had visited Kyoto in the 1920’s, and was astute to see that leaving the city intact would make dealing with a conquered Japan much easier. He batted down Groves’ repeated efforts to put Kyoto on the target list.

The book offers a rare description of the carnage at Nagasaki, ignored to this day due to focus on Hiroshima. (The city was a trading center with a large Christian population.) It returns to Hanford during the Cold War arms race in which the U.S. and Soviets built thousands of “nukies” — to borrow a word I once saw on a Richland hotel marquee – even though 300 bombs would have been sufficient to wipe out civilization in each of the superpowers.

The book covers a high point, John F. Kennedy dedicating the N Reactor in 1963, a bomb factory whose excess steam was used to make it the largest power reactor in the world. “No one can speak with certainty about whether we shall be able to control this deadly weapon,” said JFK, who would be assassinated two months later.

Hanford crashed in the 1980’s, however. The mismanagement of the Washington Public Power Supply System nuclear construction program left Hanford with two abandoned reactors and triggered the largest municipal bond default in American history. “”WPPSS,” pronounced “Whoops” threatened to melt down the Northwest economy.

The N Reactor, built around a graphite core without a containment dome, generated national controversy after the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the Soviet Union. Olson covers “The Reckoning,” but in a curious way. He devotes space to Hanford’s first anti-bomb group, called World Citizens for Peace. But there is little treatment of what really triggered red flags, an insularity, laissez faire attitude toward safety and it-can’t-happen-here mentality of managers.

On our first Seattle Post-Intelligencer investigative foray – on a ruthenium leak kept secret for 25 years – our sources were veterans of the nuclear Navy under Adm. Hyman Rickover, appalled at failure to go by the book in handling the hot stuff.

The N Reactor was permanently shut after the Roddis report, conclusions of a panel of Manhattan Project and Navy experts. They flayed management at the reactor. Two panelists wanted it shut at once, five others giving it a half-life of a couple years. The reactor never resumed operations.

“The Apocalypse Factory” takes a side trip into Tri-Cities culture. Richland was the town closely associated with Hanford, home to its scientists, chemists and engineers, many from other parts of the country. Kennewick took the overflow, served as the region’s shopping center, and was a “sundown town” well into the 1960’s. African-Americans were not welcome. Pasco was an old railroad town, home to the area’s African-American and Hispanic population.

With 177 leaky tanks of radioactive waste, many dating from the 1940’s, along with contaminants for years dumped into the soil, Hanford was targeted in the late 1980’s for a vast cleanup. The Mayor pro tempore of Richland groused that the reservation’s skilled workforce was not destined to be “janitors.”

The cleanup has fallen far behind schedule, and legal interventions by AGs Chris Gregoire and Bob Ferguson have been required to keep the federal government from reneging on its commitments. After all, the Columbia River, life stream of the Northwest, circles the reservation.

Olson has an eye for delightful detail as well. The 50-mile stretch of Columbia River, circling Hanford, is the last undammed section of river between Bonneville Dam and the Canadian border. A Hanford Reach National Monument was dedicated by Vice President Al Gore in 2000, breezes from the river exposing America’s most carefully combed over bald spot.

“Today people can walk on the chalky white cliffs across the Columbia from the cocooned reactors and watch bald eagles soar above the wind-whipped river,” writes Olson. Hopefully there is more Northwest history for this Othello boy to revisit.