- Last weekend The New York Times ran an interview featuring actor Anthony Hopkins talking about “epiphanies,” moments in his life when “God” spoke to him in life-altering ways.

- The political scientist Charles Murray is out with a new book, Taking Religion Seriously, which he hasn’t ever done until now. Murray writes, “I spent decades dismissing religion as superstition. But the more I learned, the less my own certainty made sense.”

- And New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote memorably earlier this year about his own coming to faith. There are recurring reports about Gen Z, twenty-somethings, turning to faith and church in numbers exceeding that of their parents and grandparents.

Lately I have been reading the opus of the Canadian philosopher, Charles Taylor, A Secular Age. Taylor’s breadth and erudition are astounding, and so is the length of his tome, 874 pages. I read Taylor the way I read Karl Barth, five or ten pages at a time. That is because there is so much there, but also because reading such a brilliant person and writer is pleasurable.

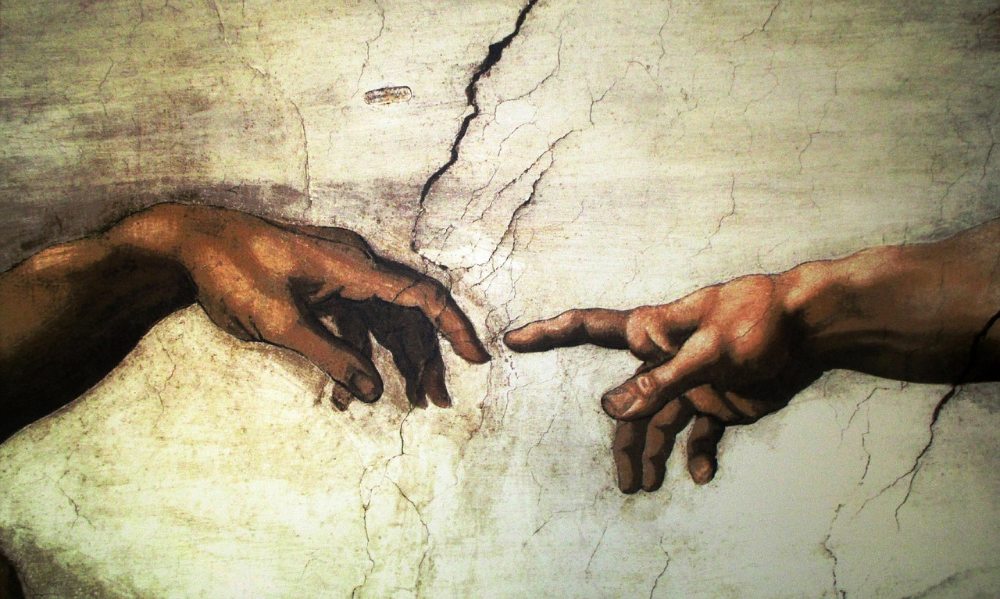

Taylor is curious about a seismic shift. There was a time when belief in God was universal and assumed, part of the fabric of life. People lived in an enchanted world. Then, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, “the death of God” (Nietzsche’s phrase) became the assumed reality. That is, if not universal, then the prevailing view in the modern west.

“The ‘death of God’ thesis,” writes Taylor, means that “one can no longer honestly, lucidly, sincerely believe in God.” Why, wonders Taylor, do the arguments for a godless, indifferent universe now seem so obvious, “when at other times and places God’s existence” seemed just as obvious?

The elements of the story our secular age tells itself are that science proves we live in an indifferent material universe, that religion is a childish illusion from which we have now been liberated, and we are “coming of age.” Now, we moderns may and must face life courageously, without illusion; we are free, absent religion’s repressions and superstitions, to focus on human welfare. Taylor calls the latter “the subtraction theory.” Subtract religion and all will be free, all will be well.

“What we got rid of were the illusions, and it took courage to do this; what is left are the genuine deliverances of science, the truth about things, including ourselves, which were waiting all along to be discovered.” This became the official story of a secular age, one predominant in western liberal culture. (I’ve had more than one encounter with a come-of-age modern person who at some point in a conversation says, as if sharing a confidence and perhaps a hushed tone, “Now truthfully, Tony, you seem an intelligent person, you don’t really believe in God, do you?”)

Taylor’s argument is that this secular materialism, rather than being a discovery about how things really are, is merely one historically-constructed understanding. But the consensus of secularity saw its view not as A construal of reality, but as THE true and only reality which all honest, rational, and courageous people must embrace.

Taylor’s book was published in 2007. The reality he describes remains pervasive, and is particularly dominant in the academy, however, things have changed. When one looks beyond the modern west and affluent, white people, it’s clear that a lot of the world’s people apparently didn’t get the secularist memo. And now some of the intelligentsia (e.g. Hopkins, Murray, Brooks) are becoming dissidents to the official story of secularity.

One of Taylor’s really interesting distinctions is between what he calls the modern “buffered self,” and “the porous self” of any earlier enchanted world. “For the modern, buffered self, the possibility exists of taking a distance from everything outside the mind. My ultimate purposes are those that arise within me . . . this self can be seen as invulnerable, as master of the meaning of things . . . the porous self is vulnerable, to spirits, to demons, cosmic forces.”

Anthony Hopkins’ reports of epiphanies, of hearing a voice of God speak to him and setting him on a different path would be an illustration, or a testimony, of a “porous” self or experience, and of an enchanted world. Here I am simply noting that such testimonies seem to have gained new traction, even respectability. Where once the respectable option was the so-called courageous, come-of-age secular man, casting aside religion as false comfort and illusion, that seems less the de-facto accepted version of late.

Where this is heading, your guess is as good as mine. Nor do I see it as all or necessarily to the good. Religion is, like most else, a mixed bag. But the cracks in the hegemony of the official story of secular modernity and materialism seem to me both worth noting and refreshing.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for this survey, Tony. I also have noticed this shift in the intellectual zeitgeist. I listened to a recent interview with Charles Murray about his new book and how he has opened up to a possibility that a god exists. (Observing his wife attending a Quaker church played a role). Another book that joins this mini-trend of becoming more open to a divine presence is Sebastian Junger’s recent book “In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face-to-face with the Idea of An Afterlife.” I heard Junger speak last year at Town Hall and was moved by the account of how his lifelong position of atheism became beset by doubt.

The existence of a God that created the universe is a lovely argument for philosophy journals, academics, and dinner parties, but is of little relevance beyond that. The interesting questions are:

– if God exists, is it interventionist, including answering prayers?

– if God exists, does it impose a moral code on us with rewards and punishments both here and in the afterlife (if such thing exists)?

– if God exists, does it want to be worshiped?

The movement away from religion over the last century is much more about the absurdity of answering “Yes” to any of these questions than about the simple question of whether the universe was created by a being with powers far beyond the physical laws of the universe as we know it.

Thanks for the comment Kevin, and for your many great contributions at PA. One of things I find interesting, and appears true of your comment, is how dogmatic many of the anti-religious are! Cheers, Tony

Dogmatic? It looks to me like the dogma in it is not his – he didn’t make up those three questions, nor the closing proposition. Didn’t that all came right out of your story? Then he does indicate that some people would find it absurd, but … you don’t, evidently.

My only doubt would be that even philosophy journals etc. can’t really take that question seriously. No one is seriously invested in the abstract proposition of an unknowable creator god that stands outside the knowable framework of the universe. Not because it’s unreasonable, but because it can”t be placed within any meaningful context.

I personally am inclined in the other direction. I don’t need my god to answer my prayers, reward me, desire to be worshiped – or even create the universe. (Some religions don’t even posit a creation, which makes sense to me.) But our sun bestows life and everything we care about, and is also mind bogglingly immense and powerful, and I think a little reverence and appreciation is called for. Real as can be, too, which for me is a big bonus.

For the record: I was raised Catholic and went to Catholic schools for twelve years, including a high school run by the LaSalle Christian Brothers, where we dived deeply into theological questions such as proofs of the existence/non-existence of God. While I am not a practicing Catholic now and am somewhere between agnostic and atheist, I am well-versed in these questions and the answers to them suggested by all parties. Over the course of my studies in College and beyond, I’ve also taken the time to learn about various sects of Christianity, as well as Judaism, Islam, Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.

If there is dogma in this space, it’s from religious practitioners who, when facing the illogic of some of their positions, declare that “it’s a mystery!” then sanctify “holy mysteries” as part of what makes their religion special and ending any further inquiry by declaring those questions as off-limits incursions into the unknowable nature of God. Or worse, they declare that “faith” — trust in the correctness of an answer without applying critical analysis — is the heart of religious practice and thus to spend time questioning doctrine is an unacceptable attack on religion itself. That doesn’t mean that all religious practitioners do that — I am definitely not saying that, and I know many religious people who do explore (indeed, wrestle) with those questions as part of their own journey. But you and I both know that many people take the answers they are told by religious leaders as unquestionable matters of faith, no matter how illogical the answers might be. That’s dogma.

We live in a world full of absurd things. It may very well be that there is an all-powerful God that created the vast universe billions of years ago and yet is interventionist today, answers prayers, imposes a moral code on its sentient creations, rewards and punishes, and wants us to worship it. But my point — to your original question — was that the notion that a being all-powerful enough to create the entire universe cares about these things is facially absurd, and it should be no surprise that over time there is a social trend toward rejecting that view of the universe.

Thanks Kevin. To me “dogmatic” in this context means being completely and absolutely certain, which is something that some of both the religious and non/ anti religious seem to have in common. The data on belief and religious involvement does suggest a downward trend among white, affluent people in western world. Globally that is not the case.

There is a world of difference between an organized religious doctrine and a deep human longing to make sense of life, especially in recognition of the (to me) unfathomable intelligence and complexity of living beings. This life! This gift of consciousness! It can make ya wanna jump outa bed in the morning and get ready to be awed!

And some say

“Thank you, God, if you exist for making me an atheist”.

One might plausibly argue that what we are really seeing is increasing disenchantment with the overblown claims of secular materialism to owning a monopoly on our understanding of reality. To what extent this bodes well for a resurgence of traditional religions is a separate question. To be sure, the first stop for many newly disenchanted materialists will be to check out the existing off-the-shelf religious inventory. But then many may just shrug their shoulders and move on. This could be a really great time to look into starting a new religion.

A good article — and even better comments by Kevin Schofield. I also was raised and schooled Catholic: mass every day before school, “JMJ” at the top of every paper (including math tests) handed in; confession every Friday and Communion every Sunday (excepting if masturbation or “impure thoughts” on Saturday; deep discussions about faith and God in religion classes at a Jesuit high school (where the only non-Jesuits were the sports coaches); and then reading the “Great Books” from the Gita to Heidegger (why does anything exist?) to Gerard Manley Hopkins at Seattle University. All of which inculcated in me the same questions (and answers) expressed by Schofield. Although, unless I missed something, nobody raised the belief in Pantheism — that everything, including gravity and every bit of matter and non-matter and dark matter, is and always has been eternal and everlasting “God”.