This is an excerpt from Ramsey’s book, Seattle in the Great Depression (WSU Press, 2025).

The Washington State Ferries — the second-largest car ferry system in the world after BC Ferries — will celebrate its 75th anniversary next year. Now under state ownership, its history goes back much further.

Our ferry system begins with the founding of the Puget Sound Navigation Company in 1898, the year of the gold rush to the Yukon. The founder, Charles E. Peabody, is the scion of a maritime family in New York. He revives the name of a steamship line the Peabody family had run on the Atlantic Ocean: the Black Ball Line. Its flag has the same design as the flag of Japan, except that it’s a black sun in a red sky.

In the 20th century’s first three decades, movement around Puget Sound is easier by water than on land. The Black Ball boats are part of the “mosquito fleet,” which moves passengers and goods up and down Puget Sound — from Tacoma to Seattle, Seattle to Everett, and so on. But in the 1920s, the roads get better, and cars, trucks and motor stages (buses) begin driving off with the mosquito fleet’s business.

In October 1929, two weeks before the Wall Street crash, Charles Peabody passes the reins to his Cornell-educated son, Alexander Peabody, 34, who has been vice-president of operations. The son’s first act as president is to put together an investor group to fend off a hostile takeover. He keeps control of the Black Ball Line and will run it for the next two decades.

By the 1930s, the company’s urgent need is to reorient its service to moving cars and trucks across the Sound. But the Depression makes the purchase of new ferries difficult. The traffic is too low to pay for new boats. In 1933, Peabody buys the steel hull of the San Francisco Bay ferry Peralta, which has burned to the water line.

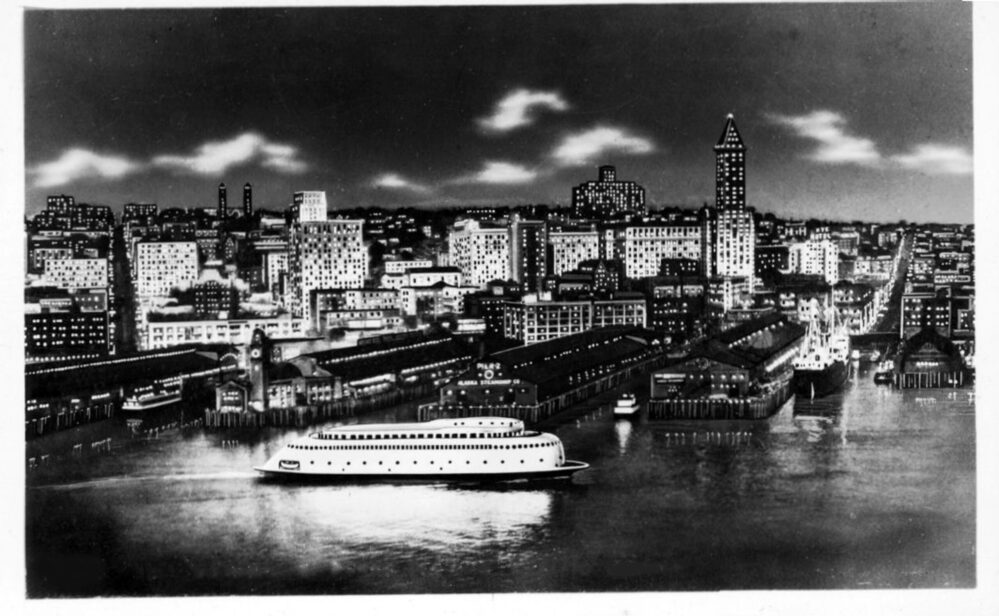

He has the damaged hull towed to a shipyard on Lake Washington, where the topside is rebuilt in a radically streamlined form and launched in 1935. Named the Kalakala, people call it the “silver slug.” It is Peabody’s favorite boat. In 1937, the opening of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge removes the need for ferries there, and Peabody buys 17 of Southern Pacific’s boats at bargain prices.

The Depression brings other problems. For decades, the Puget Sound ferry lines were free to set their own schedules and fares. But as they consolidate, fear grows of private monopoly. After 1927, the fees charged by private ferries are subject to state regulation. Next come the unions. In the early 1930s, Captain John M. Fox organizes the licensed officers in the Masters, Mates & Pilots. The deck crew is organized as the Ferryboatmen, renamed in 1936 the Inlandboatmen. In 1933 the unions strike and win recognition.

Four times in the 1930s, strikes shut down the Black Ball Line. In the unions’ big year, 1937, the Inlandboatmen shut down the ferries for 27 days. Arbitrators award the deck crews a 30 percent increase, which Peabody pays under protest, stating that it is “far in excess of wage and hour conditions required of other employers of maritime labor.” The state allows Black Ball a 7 percent fare increase on the heavily traveled Seattle-Bremerton run and up to 60 percent on some of the smaller, money-losing runs.

In 1939, the Inlandboatmen strike again for higher pay. This time, Peabody is dead set against any concessions. “The Puget Sound Navigation Company [the corporate owner of the Black Ball Line] has paid no dividends since 1929 and during several seasons since that time has operated at huge losses,” he says. The strike lasts 23 days, after which both sides agree to arbitration. The union wins a small increase.

The strikes sour the public on the private ferry company. In the 1937 strike, Seattle Mayor John Dore demands that Gov. Clarence Martin seize and operate the ferries. In 1939, the Seattle Star calls for the state to lease the boats and operate them. Union leader Fox calls for a complete state takeover of the Black Ball Line.

None of these things happens then, but Peabody is publicly demonized. Vashon resident Betty MacDonald, author of the best-selling novel The Egg and I, denounces Peabody in 1939 on a radio show promoted as “The Bad Egg and I.”

World War II gives the Black Ball Line a reprieve. By carrying Seattle war workers to the Bremerton Naval Yard, the company is able to lower fares and still make money. But at war’s end, federal wage and price controls come off, and America is convulsed with strikes. In March 1947, the Marine Engineers shut down Black Ball’s fleet for six days and win a 24 percent increase in pay.

Peabody demands that the state allow a 30 percent increase in rates, and the state gives him 10 percent. Outraged, in March 1948 Peabody shuts down the fleet, demanding his 30 percent. This is a strike not by labor against a company, but by a company against the state. When the state refuses to budge, Peabody leases the boats to county governments, which aren’t under the state’s control — and they sign contracts for him to operate the boats at his prices.

The cost to carry a car and driver from Seattle to Bremerton, which was 80 cents during the war, jumps to $1.85 ($27 in today’s money). The service resumes, but users are angry — as are state politicians, who have been bypassed. Republican Arthur Langlie, elected as governor in 1948, accuses Peabody of bringing private enterprise into disrepute, “even though in some ways I admire the old buccaneer.”

By 1948, the political environment has changed. Between the state and the unions there is no room for private ownership of the Puget Sound ferries. In March 1949 the legislature passes a law allowing the state to enter the ferry business, and the Republican governor signs it. After much negotiation, Peabody sells his company for $4.5 million ($56 million today). On June 1, 1951, the Washington State Ferries takes over the domestic ferry service, making it part of the state highway system. It leaves the run between Port Angeles and Victoria, B.C. in the Black Ball Line, which is still running one ferry, the MV Coho, 74 years later.

The Washington State Ferries cuts the Seattle-Bremerton fare by a nickel for a while, then raises it back to Peabody’s prices. It uses Peabody’s ferries for decades. The last four of the boats Peabody bought in San Francisco in 1937 — the Quinault, the Nisqually, the Klickitat, and the Illahee — run until 2007.

The streamlined Kalakala is smaller and narrower, and not as efficient. It is taken out of service in 1967 and sold for use in Alaska as a barge for a seafood processor. At century’s end, the Kalakala is tied up in Lake Union, and then at Tacoma, waiting for someone to restore it, but no one does. In 2015 Alexander Peabody’s favorite ferry is scrapped.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great article! Can’t wait to read your book.

I was sad the Kalakala was scrapped, but drove down to Tacoma for the scrap sale and treasure my 2 small pieces of the Kalakala.