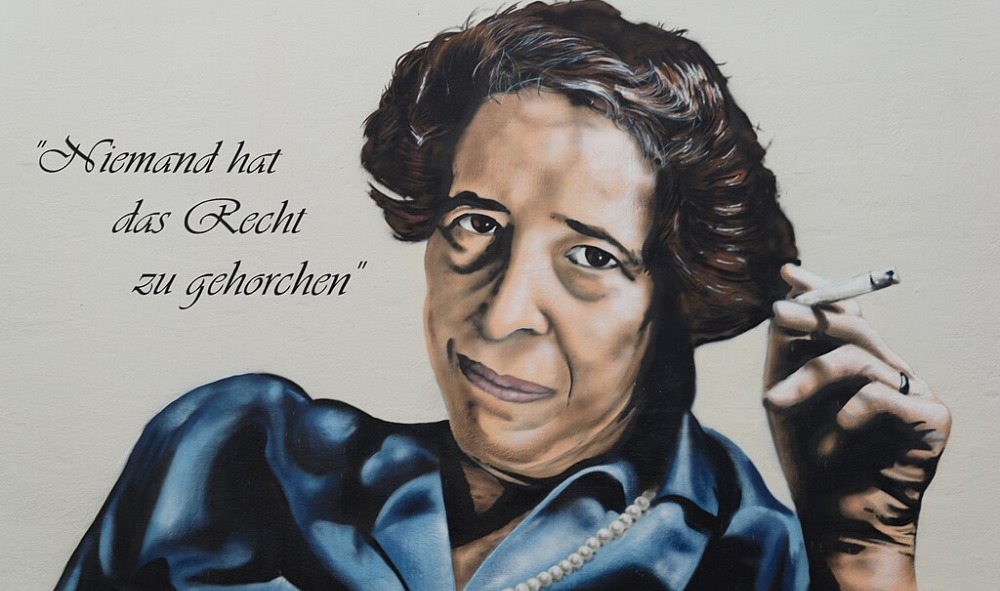

I had the great privilege to know the late social philosopher, historian, and chronicler of totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt. In the spring of 1965, when I was barely 23, I was in a seminar with her at the University of Chicago. She has been my philosophical and moral anchor since that time.

Arendt was a German Jew who had escaped once from Germany, in 1933, and again from Vichy France in 1941, in both cases having been “detained” by authorities — detained in Germany because she spoke and wrote against German antisemitism, detained in France because she worked for Zionist groups, brought attention as she could do the growing catastrophe of European Jewry, and worked to get Jews to Israel.

In 1941, with the grip of Vichy (collaborationist) France tightening, Arendt along with the artists Max Ernst and Marc Chagall, the writer Horace Mann, and many others, was spirited out of the country by the journalist Varian Fry and diplomat Hiram Bingham. Those two men secured exit papers and American visas and were responsible for moving some 2,000 refugees through Marseille to safer grounds.

Arendt came to the US in 1941, and continued working with Jewish groups to bring attention to the horrors in Europe. She also continued to pursue philosophical interests. Her genius would link the politics of the day with older thought, culminating in the 1951 publication of The Origins of Totalitarianism. Totalitarianism, said Arendt, was something new, something beyond old concepts of autocracy and dictatorship, because it was “total,” its reach extending to the all-encompassing remanufacture of truth.

In Nazi Germany, where children were encouraged to spy on parents and the “truth” was as mercurial as the leader’s daily pronouncements, Arendt said that “The thousand-year Reich” became as believable as the idea that your neighbor would still be your neighbor the next day.

In 1961, Arendt went to Jerusalem to cover the trial of Adolf Eichmann for The New Yorker. One of the primary architects of Germany’s “final solution” of the “Jewish problem,” Eichmann had escaped the Americans at war’s end and made it to Argentina, where he worked at a Mercedes-Benz factory. In 1960, he was discovered, apprehended and taken to Israel to stand trial.

Arendt’s coverage immediately caused ripples, especially in Jewish communities. Eichmann, Arendt told her readers, was judged by the psychologists to have a “normal mind.” They could find no locus of evil in the mind of a man who had been responsible for the deaths of millions of Jews, Gypsies, communists, and homosexuals. “Normal” people could be made to do terrible things, said Arendt, and she called her account “A Report on the Banality of Evil.”

Jewish intellectuals and politicians, and most of her readers were not ready to admit that this could be true, that atrocities could come from “following orders.” They were further outraged when Arendt said that Jews could have done more while in the grip of German totalitarian power; and further that there had been Jewish accommodations that only made the Nazi grip stronger.

World Jewry was loudly critical. Arendt’s counter was the Warsaw uprising, where Jews had organized and revolted. Although thousands were deported to the killing factory at

Treblinka, thousands more were killed during the month-long resistance as the Germans tightened their grip and starved and killed. As many as 20,000 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto survived. More importantly, their stories survived.

I invite you to compare these stories with the lame denials of Bibi Netanyahu and the sycophant American ambassador Mike Huckabee. Ask why so many Palestinian journalists have been killed, and why foreign journalists have been denied access, and why the un-doctored photos and videos of starving Palestinians are believed by most of the world but not, apparently, enough of Israeli and American politicians to make a difference.

The truth, I wager, will out. It will take time, and Jews around the world will suffer from a backlash from the rest of the world for their government’s prosecution of the Gaza war. Or they and we Americans will ultimately admit our complicity in what are called now and will be judged in the future as “war crimes.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sheesh.

Thank you for your reflection on Hannah Arendt. A recent homage to Arendt is a well written work by Lyndsey Stonebridge, an Englishwoman, titled “We Are Free to Change the World.” Arendt endured the struggles and sufferings that permeated so much of the 20th Century and left an erudite oeuvre for us to ponder in the perilous climate of our present time.

Not Horace Mann, I think, but Thomas (no relation) or Thomas Mann’s lesser-known older brother, Heinrich.

It was Heinrich Mann. https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust/personal-story/hiram-bingham-jr

Yes, Heinrich. And Golo, Thomas’ son, and thousands more. So I read in Varian Fry’s wikipedia page. He and his associates were mostly working against their own sponsors as well as the Vichy/Germans.

Wow. I’m rereading “Eichmann in Jerusalem” now, and imagine the Israeli authorities could not have been pleased when she said the Holocaust could not have happened as it did without the cooperation of the victims, especially their leaders and police (pages 115, 117-119). Eichmann himself was surprised at this and admitted that he and a few thousand people, most of whom worked in offices, could not have been so successful otherwise (p. 117). In countries that resisted – Denmark, Sweden, Bulgaria, even Italy – there were far fewer deaths. She also protested against the mild consequences after the war for most of the Germans who took part in these horrors. Will there be consequences in Israel?

Many thanks to Mark for the excellent link. I now recall reading about Thomas and his wife being out of Germany at a critical moment and getting a message from one the children, somewhat coded, that advised them not to return to Munich (I think it was).

And I had forgotten about Golo, and have been hoping to find out how he made his way to UC Berkeley. Should be on line somewhere.

Interesting reading is “Weimar on the Pacific,” about the confluence of German exiles in Los Angeles before, during and after the war.

“Ask why so many Palestinian journalists have been killed”: because they are in a war zone, and many of them are members of Hamas.

“and why foreign journalists have been denied access”: because it’s a war zone, and some of them could get killed; worse, some of them could get taken hostage by Hamas, and used as another tool for extortion against Israel and against their home countries.

“and why the un-doctored photos and videos of starving Palestinians are believed by most of the world but not, apparently, enough of Israeli and American politicians to make a difference”: Oh, you mean the undoctored photos of children suffering from GENETIC DISEASES like muscular dystrophy rather than hunger, whose unaffected siblings standing nearby were cropped out of the photographs so that they could appear more pathetic? Or do you mean the photos of starving children in Yemen that have cynically been used as if they showed children in Gaza?

“The truth, I wager, will out”: I hope so, but people like you, who are credulous toward every anti-Israel libel, certainly don’t help.

“Jews around the world will suffer from a backlash from the rest of the world for their government’s prosecution of the Gaza war”: Oh, give me a break! Jews around the world started suffering a “backlash” while the dead victims of Hamas’s invasion were still warm! As if Jew-haters need reasons for their hostility and violence against Jews!

I read Eichmann in Jerusalem when I was an undergrad in the late 1980s. The book had a profound impact on shaping my view of human nature, and about how the world works. The “banality of evil” is up there as one of the most important insights of the 20th century. I really regret I never got around to reading The Origins of Totalitarianism.

I am fascinated by Arendt’s torrid affair with — and then her long post-war friendship with — Heidegger, give his embrace of Nazism.