World leaders led us in marking D-Day’s 80th anniversary on June 6. But there is much left to commemorate this month: Friday, June 14, is Flag Day, the day we honor the stars and stripes (hopefully flown right side up). Sunday, June 15, is Father’s Day, just prior to marking this year’s Summer Solstice at 1:50 pm on June 20. There’s also Juneteenth, National Independence Day, now an official federal holiday. And, throughout June, there are multiple occasions to observe Pride Month.

Falling amidst these special days is June 15, a date most will neglect to observe or even notice. It is the 165thanniversary of the defining incident of the Northwest’s Pig War, a war worth remembering.

On that long-ago day, Lyman Cutler, a U.S. settler on San Juan Island, discovered a pig rooting in his potato patch. It wasn’t the first time Hudson Bay Company livestock had blundered into Cutler’s garden. But the pig’s transgression (gobbling up costly potato seed) was the final straw.

The enraged farmer grabbed his double-barreled shotgun and killed the hapless hog. Later that day, Cutler had second thoughts. He walked over and apologized to Charles Griffin, manager of the Hudson Bay Company’s Bell Vue Farm, offering to pay him $10, an amount Cutler thought would cover his hasty action.

But Griffin wasn’t buying the apology. Heated words were exchanged and then the hotheads took over. U.S. General William S. Harney of the Department of Oregon, notorious for his dislike of the English, ordered his subordinate, Col. George Pickett – later of Gettysburg fame — to leave his post at Fort Bellingham and establish a base on San Juan Island.

Hudson Bay’s Griffin reported the pig incident to James Douglas, HBC governor of Vancouver Island. Douglas had no respect for Gen. Harney, whom he felt had “spent a lifetime warring against Indians.” Besides, Douglas, also serving as Hudson Bay factor, was outraged over Whatcom County attempts to tax the company farm. He dispatched his son-in-law to check things out.

RED Through Rosario Strait, favored by Britain

GREEN Through San Juan Channel, compromise proposal

The lines are as shown on maps of the time. The modern boundary follows straight line segments and roughly follows the blue line. The modern eastern boundary of San Juan County roughly follows the red line.By Pfly – self-made, information one boundaries from Hayes, Derek, Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest., CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Underlying the dispute was confusion over whether San Juan belonged to the United States or to Great Britain. An earlier settlement had clouded ownership. Was the international borderline located along de Haro Channel? Or was the international line farther to the East at Rosario Strait?

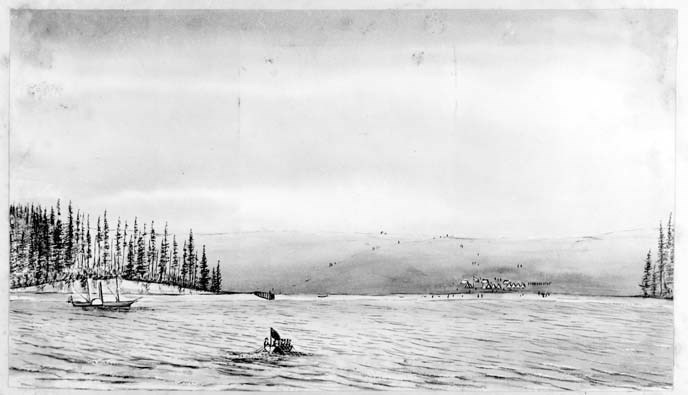

The confrontation continued to escalate. Pickett arrived commanding a group of 66 soldiers and set up camp on the South end of San Juan. Soon they were facing three armed British warships anchored off the island’s north side.

Learning that Harney was planning to reinforce the American garrison with 450 men, Douglas ordered Capt. Geoffrey Hornby to land his troops. However, Harney disobeyed and was backed up by British Rear Admiral Lambert Baynes. The admiral declared he would not involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig. He said, “I’d rather shed tears than shed a drop of blood.”

When he learned about the saber-rattling, President James Buchanan was much distressed. The dispute was not welcome at any time but especially when the country was dealing with turbulent North-South tensions. Buchanan dispatched Gen. Winfield Scott (“old fuss and feathers”) to resolve matters. Scott, an accomplished peacemaker, gained the trust of Douglas and was able to work out joint occupation of the island until sovereignty could be settled by arbitration.

However, resolution was slow in coming. With the Civil War about to erupt, followed by outbreak of the Prussian War between Germany and France, the San Juan dispute would languish for a dozen years.

During that long delay, the opposing camps on the island faced one another with surprising calm. The commanders made a practice of declaring a truce at Christmastime: an opportunity for joint feasting. There were casualties during those years, but no hostilities. On a hill high above English Camp, there is a cemetery with hand-hewn crosses. During occupation, a dozen men succumbed to various misadventures: drowning, knife fights, and illness.

The two nations had submitted their claims to an international commission. Finally on March 5, 1871, the panel of three arbiters began discussions of unsolved Civil War claims, Canadian fishing rights, and the San Juan boundary. The first two issues were quickly settled. Then by a 2-1 vote, Americans were given full claim to San Juan Island, which sits strategically at the entrance to the Salish Sea.

German Kaiser Wilhelm I, who oversaw the arbitration process, ratified the commission decision on Oct. 21, 1872. The Treaty of Washington followed, signed on May 8, 1873, signaling the parties’ formal recognition of the decision.

Yes, there was grumbling in British newspapers. However the British public accepted the decision as a minor setback to a nation with a vast empire. English Camp troops left quietly after a friendly sendoff and the Americans raised the Stars and Stripes. With difficulties settled, the waters of San Juan and other islands had been secured.

Years ago, I visited San Juan Island while enrolled in a University of Washington class on the Pig War, a weekend-long seminar with lecturers from the history department. We toured British Camp with its well-preserved blockhouse, climbed the hill to the cemetery and then visited the wind-swept site of American Camp. The U.S. Parks Service today maintains both historic sites.

The main take away from that UW class was a deep admiration for the nations’ joint decision to submit their disputed claims to arbitration rather than going to war. That war never erupted in carnage, instead into a bloodless battle save for that unlucky pig. Would that the devastating wars in Ukraine and Gaza could be settled by some similar international arbitration, achieved without the massive destruction and loss of life.

The Pig War remains my favorite war; I simply can’t help wanting to celebrate June 15 and one war that was over before it started.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I still prefer The War of Jenkins’ Ear, England vs. Spain, 1739 – 1748.

According to the locals near English Camp I got this nugget: Yea, the armies had some days that were rather unstructured. The 2 sides fighting this “war” would get together often and play cards and drink. Then go back to their respective posts.

Love local color even if it isn’t in the history books.

Most informative and welcomed reading.