In the material world, nothing is done by leaps, all by gradual advance. — Theodore Parker

I stumbled across ancient history in the sixth grade. Tales of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman times thrilled me and led me to learn to read and use indexes (my parents had a World Book Encyclopedia whose index pointed me to every entry, and that opened Roman and Greek history to me). Ever since, history enthralled me. In the intervening years, much has changed. Card catalogs left libraries, and research decks left researchers – all to be replaced by the internet and digitized data.

The reality of the impact of this information revolution on historical scholarship became real to me when Doris Kerns Goodwin released her Team of Rivals. Kerns Goodwin made connections regarding the politicking around the formation of Lincoln’s cabinet, connections impossible for a mere card deck. Who was where when? Who wrote what letter to whom, residing in an obscure library? The insights made the story more complex and compelling than the old-method historical narratives.

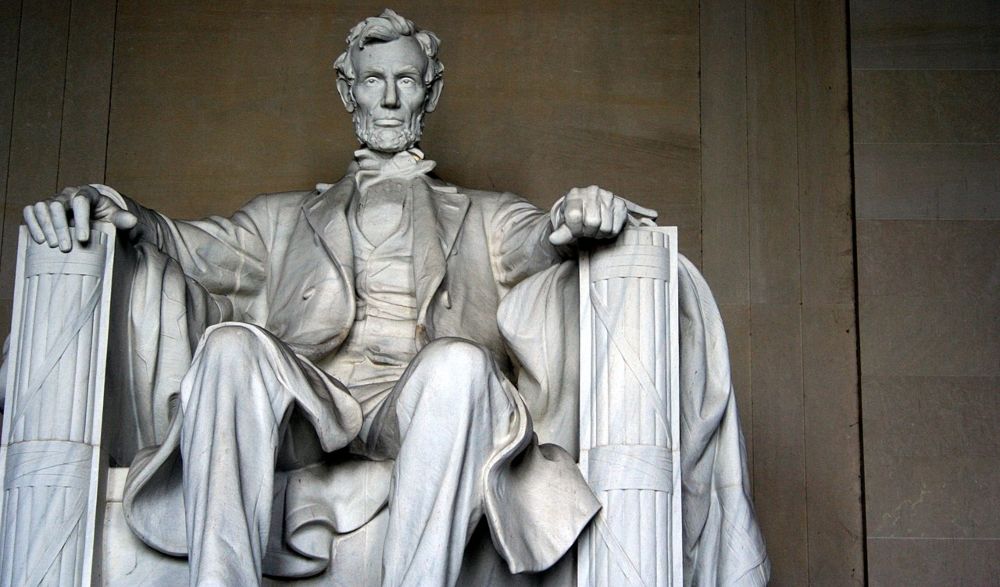

And There Was Light, by Jon Meacham, is the latest in this string of “new” histories in my library. In many ways Meacham tells an oft-told story. Young man grows up in poverty on the frontier, splits rails, self-educates, and becomes a lawyer and the statesman who saved the union before a dastardly actor assassinated him during the play Our American Friend. The story becomes mythical and destined for retelling for new audiences, new challenges, and new generations.

Meacham’s retelling clearly believes the United States is/are (the conjugation changed to the singular by the Gettysburg address, according to Garry Wills) in such a crisis, and that Lincoln can light our way to bend the moral arc of the universe more toward justice. The book with its warnings about the dangers to democracy posed by the Slave Power is rich with contemporary echoes.

Meacham’s retelling has two major insights. First, he synthesizes Lincoln’s formative years and the 18th and early 19th century debates about slavery and emancipation. Second, he elucidates what Meacham believes to be Lincoln’s three distinctive gifts for bending the moral arc toward justice.

Meacham tells of young Lincoln’s church attendance followed by shirking his chores to re-preach the minister’s sermon to a gaggle of children, Lincoln perched on a stump in newly created frontier farmland and enjoying the public attention to his artful words. Meacham tracks down the ministers Lincoln heard and their preaching about slavery. David Elkin, for example, whom Lincoln asked to come preach at his mother, Nancy Hanks, funeral, and his partner David Downs are both noted as antislavery Baptists. For Meacham, Lincoln early learned the evil of slavery, rather than being dragged into it to win the Civil War by using Black troops.

Establishing this early inculcation against chattel slavery, Meacham develops the theme throughout Lincoln’s political development and growing religious belief. Lincoln realized the difficulty of emancipation and the depth of 19th century racism, even in the North. A line I’d not heard before, from Fredrick Douglass, became one of my favorites: “He never shocked prejudices unnecessarily. Having learned statesmanship while splitting rails, he always used the thin edge of the wedge first – and the fact that he used it at all meant that he would, if need be, use the thick as well as the thin.”

Meacham argues that Lincoln used this gradual wedge three crucial times. First when Congress struggled with a compromise to keep the union by enacting a 13th Amendment denying the ability to abolish slavery in any state. Lincoln’s ambiguity kept negotiations alive, held the Republican Party together, and focused attention on the South’s secession and ambitions to extend slavery. Meacham makes clear that the Southern states aimed to extend slavery within United States territory and intended to extend it to Cuba and other Latin American territory, creating a hemispheric slave empire.

Second time was when the President was pressed to backslide on the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862. A lonely Lincoln stood fast, holding the Proclamation until after victories at Antietam in September of 1862 (against Lee) and the 1862 midterm elections. Republicans defeated Copperheads (pro-slavery Democrats) in the 1862 midterms thanks to Republican efforts to expand absentee voting and assure that these states counted Union soldiers’ votes. In states where Democrats controlled and refused to authorize such absentee voting, the administration worked to furlough soldiers so they could return home and vote. It worked, and so on the New Year emancipation was proclaimed.

Third time, again under enormous pressure, Lincoln refused a negotiated peace in 1865, one proposed by Francis Preston Blair and Alexander Stephens, the Confederate vice president. That episode threatened, briefly, the passage of the 13th Amendment. Lincoln went so far as to leave Washington to meet Stephens at Hampton Roads. There he made clear that “peace had to be founded on the restoration of the Union, and the restoration of the Union began with ‘those who were resisting the laws of the Union cease that resistance.’” End of story.

In each of these crises, Lincoln proved true to his statement “I may advance slowly, but I don’t walk backward.” He was moved, in Meacham’s words, “toward a future in which race would be irrelevant to human rights not only in theory but in practice.”

The strength in Meacham’s tale stems from his understanding and ability to evoke the nature of politics in a complex democracy, and in elucidating Lincoln’s grasp of that nature and how to move it forward.

Meacham’s book focuses squarely on slavery and the Slave Power. The interest of Confederate leaders in a slavery-based nation was seen in behavior of people like George Bickley and his Knights of the Golden Circle’s effort to colonize Nicaragua and to invade Cuba. All led up to the Civil War and the South’s expectation of a swift victory.

The Free Labor element of the Republican coalition remains absent from this tale. Free labor formed the basis for the Republican’s interest in infrastructural improvements such as transcontinental railroads, land grant universities, and the Homestead Act. All these were part of the divide between the industrializing North and the South’s Slave Power. Heather Cox Richardson’s To Make Men Free, a history of the GOP, makes a great companion read for Meacham in this regard.

Meacham’s book does a great service for our time, reminding us that progress is possible, that it takes not wishes but much difficult and painful work, and that, in Lincoln’s words, “with public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed.” Lincoln’s life helps us to know where to put the pointy end of the wedge, and to have the courage to use the thick end. To know the proper use of a political edge takes more than one lifetime — unless that life happens to be Abe Lincoln’s.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Fred- a wonderful and thought provoking piece. I am glad I have some book store credits still, another great read I need. I am fascinated by Lincoln, have been studying up on him for years, and these are great insights. Was great to see you in Olympia last week.

Thanks, Larry. Was fun to be back in Olympia in person for a change. Good to see you as well!

Thought provoking indeed. Thank you, Fred. Also good to see the mention of Heather Cox Richardson. I enjoy her daily equally provocative writings.

A paternal relative returned home to nurse his wounds from Shiloh. A colleague of Lincoln in pre-war Illinois law, he then ran for Congress as a “War Democrat.” Isham lost to the “Peace Democrat” but became Illinois’ top military administrator. He was with the President in the afternoon before he visited Ford’s Theater. He declined an invitation to attend. My Egyptians were from southern Illinois :). It’s off to purchase Meacham’s book, to add McPherson, Kerns Goodwin, Wills and so many others on my shelf.

Mighty timely, Fred. We’re a nation once again sorely in need of such skill and wisdom. Now that I have more time myself I’ve been able to catch up with my reading of history – and more importantly, the time to think about it. Add Jill Lepore to your nightstand if you haven’t already. “These Truths” is a wonderful survey.

I miss our occasional chats, BTW. Lori sez “Hi.”