In 1949 my family settled east of Alderwood Manor. In 1916 the Browns Bay Milling and Lumber Company had cut down its 81 million board feet of fir, hemlock, pine, cedar, and spruce and sent the logs rumbling down tracks to Lake Washington and the saws. Photos taken of the area shortly afterwards look like scenes of Hiroshima after August 6, 1945: a few charred poles punctuating a level ruin.

Our family lived in ragged second-growth trees regularly limbed or topped by power line crews and storms. Before the roads were paved, I remember being driven past isolated trees caked with dust, beaten into a shambles – an image of life itself crushed and degraded. But as developers bulldozed the trees, weeds poked up and mocked.

For American settlers on Puget Sound, mature trees blocked visions of growth. Seattle pioneer Henry Allen Smith (Chief Seattle’s putative speech writer), anted up his speculator’s bet by purchasing land at the Snohomish River mouth in addition to his claim on Elliott Bay, hoping a transcontinental railroad would find one. Without huge investment Smith thought the intervening coniferous forest an impassable barrier to progress. County officials taxed uncut land to hasten clearance. Companies like Pope & Talbot purchased immense tracts, exporting billions of board feet across the Pacific.

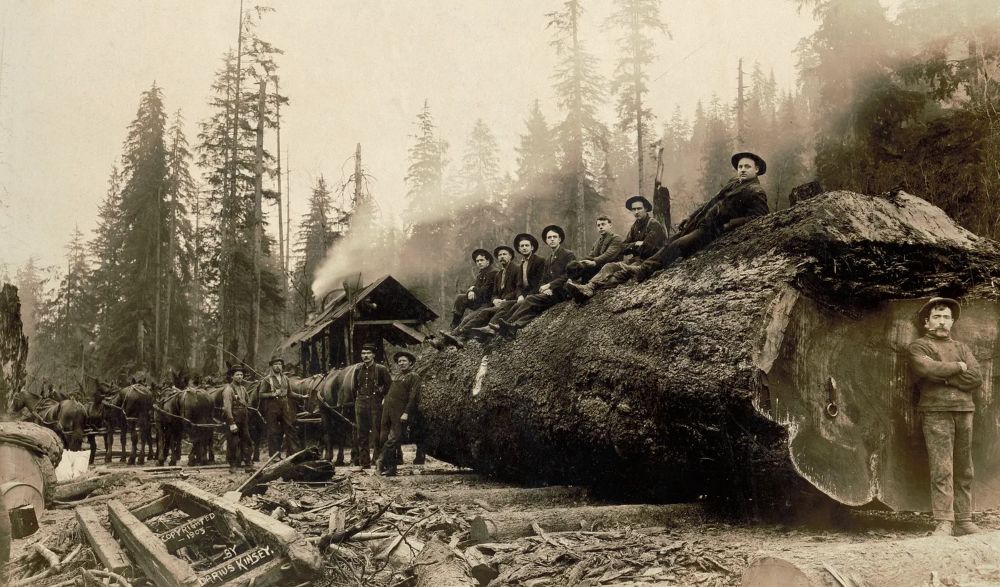

Except for a few, clearing land brought wage work rather than prosperity. Spawned by the Great Northern Railroad in 1891, the city of Everett was expected to flourish like other terminus towns, but a boom-and-bust economy gave it a blighted history. Acidic, cut-over land sustained fruit trees and dairy, but that business and some chickens granted mostly genteel poverty. Photos of proud axmen atop gargantuan logs on flat cars celebrated a short and ambiguous heroic age.

Left alone, meanwhile, seedlings grew into shaggy masses until they blocked a view. Those surviving the chainsaws continue growing, adding to homeowner fears of windblown monsters crashing through the ceiling.

Ironically, we are now at a point where the new forests resemble those photographed in the latter 1800s, when the cutting began. Trees I grew up with are now 107 years old, and some are 100 feet tall. Those surviving earlier cuts approach 170 years old. They surprise with an unexpected grandeur.

The magic of great trees found architectural expression in the classical Mediterranean style. Migrants from the Pontic-Caspian Steppe entering temperate forests built large, rectangular megarons–“long rooms”—with roofs supported by massive trunks debarked by draw-shaves. These shaves left long grooves to heighten verticality—a motif preserved in marble fluting. A holy place walled-off from the profane and protected by a forest of columns describes the Athenian Parthenon.

On the Sound, mighty baulks of timber shaped from Western red cedar raised high the roofbeams of communal longhouses. Gabled temple pediments and longhouse roofs recall the trees’ pyramidal crowns. In Seattle these elements are best seen in the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center on West Marginal Way: massive cedars rise in glorious, golden announcement. In these edifices columns, not the walls, support the roof: the strength of ancients sheltering the genius of the people.

Left alone, natural groves of conifers protect outer trees from wind, for in a storm trees behind support those facing the blast. So sited, a healthy tree’s root base will broaden into a sturdier hold-fast. The groves’ capacity to reduce wind velocity also shelters trees on its lee. Accordingly, unnecessary thinning invites blowdowns.

Heading north on I-5,, beetling forest headlands appear destined to collide over the freeway. Sound Transit’s shearing of shoulder forests reveals splendid interior colonnades. Immediately beyond the Mountlake Terrace transit station, a curving, arching overpass soars into view, a thrilling response to a resurgent green.

That happy marriage of megaflora with modernity points to a possible future. Unthinned forest blocks sunlight, causing lower limbs to wither and drop. Left alone, the colonnades will rise 100, 200, 300 feet above a shadowed floor. The nave of Beauvais Cathedral, Europe’s highest, rises 154 feet. The tallest Douglas fir, cut in British Columbia’s Lynn Valley, reliably measured 415 feet but was missing its top. The world’s tallest living tree is northern California’s Hyperion, Sequoia sempervirens, measuring more than 380 feet albeit stunted by woodpeckers. In the Olympic rainforest, Washington’s tallest tree is the 248-foot Queets Spruce. Seattle’s “Roosevelt Tree” in Ravenna Park measured 264-feet until cut into 63 cords of firewood.

Commercial cutting of Puget Sound’s old growth began in earnest at Seattle, where many of the old photos were taken. More recently the city has passed ordinances protecting flora deemed “exceptional” or “heritage trees.” Seeking the forest primeval once required a trip to a National Park. Now it rises renewed along the freeway, at Schmitz, Seward, and Discovery Parks — and next door.

Left alone, these forests will last thousands of years and rise to immense heights. Can we live in such close proximity? The Duwamish did. One of their strategies was to burn forests regularly. Studies reveal that at least 60 percent of the lowland forest was burned over every three to five years. Such manipulation created hunting parks with trees widely spaced so sunlight could nurture the herbage game herds required, and to control debris and overgrowth threatening catastrophic burns. Ancient giants punctuated a forest with an average age of 150 years.

When Captain Vancouver arrived in 1792, expressing astonished disbelief at a landscape blessed with beauty and bounty absent “the hand of man,” we know that what he unknowingly witnessed was millennia of handiwork and management by the Duwamish and their neighbors.

They had for 5,000 years so successfully managed the fishery that settlers gaped at prodigal salmon runs and herring schools. It took Americans less than three generations to obliterate these. Facing that and swallowing smug superiority, the Americans finally asked native fishers to help manage what survives. The same holds true with forests. We would do well to listen to the embattled Duwamish Tribe for what they alone can offer the megalopolis planted in their homeland.

In the 1850s, the cut began. But will these rebounding trees survive folly that now includes global warming?

Conifers are very old, appearing in the fossil record over 300 million years ago. They survived the great end-Permian extinction that killed 95 percent of all life on the planet. In its grim aftermath the conifers thrived. They became massively tall in competing for sunlight and to escape the trimming teeth of long-necked sauropods. The shadowed naves of our forests throng with ghosts of frustrated dinosaurs.

After an asteroid killed the terrible lizards, an explosion of more than 300,000 species of flowering plants—angiosperms—reduced living conifer species to 659, but they still dominate. Only one flowering plant, Eucalyptus regnans, native to Australia and Tasmania, can rival conifers in height.

If, as predicted, the climate grows warmer and atmospheric rivers become the new normal in the Pacific Northwest, that would describe the climate of northern coastal California where Hyperion reigns. Great forests are probably here to stay for a while longer.

Great trees senesce, and as they age, wear and tear takes its toll. Limbs fall thunderously. Fires scar, winds behead, nesting birds stunt, spores and insects kill. But standing or felled, they remain monuments of their own magnificence. The wondrous scale of the Earth finds its measure in life’s immensity.

To find wholeness and rest, I need only to crane my neck and survey centuries of elevation, where involuted folds rise like prayerful orants, distant mighty arms raised to a divine sun.

The forest has turned you to your poetic side, David. My Shoreline neighborhood is graced with tall firs in the hundred-foot range, but the residents below have an uneasy relationship with them. Residents trim lower limbs to let in light, which reduces overall wind resistance, and the upper limbs then snap off more often as the trees, in small clusters rather than sustained forests, gyrate more energetically in higher winds aloft. A single branch which dropped into my yard this winter measured more than a foot in diameter and crushed furniture, planters and other structures. Had it hit the roof, it could easily have gone through to the basement. Each such event brings a chorus of demands for more trees to be felled, further exposing the rest. Several of my neighbors have swimming pools. They are not at risk from crushing branches, but are happy to egg on the logging process among their neighbors, simply to get more sunlight and fewer needles and cones falling onto their pools. I’m guessing pool maintenance was not an issue for the Duwamish a few centuries ago. As far as I know, local building codes don’t require that structures be able to withstand falling logs–this would require much stouter (and more expensive) scantlings. In any case, the current stock of stick-built housing beneath the trees in our suburbs and exurbs was not built to survive timber from on high, so I imagine the giant conifers will pay the price.