Growing up on Bainbridge Island, Gina Corpuz spent a lot of time involved in the Filipino world of her father. She was unaware that her mother came from the Squamish Nation in British Columbia. Corpuz didn’t know that her mother had been wrenched from her family when she was five and sent to an Indian Residential School, or that at age 15 she came to Bainbridge Island with other First Nation women recruited to work in the strawberry fields that once covered the island.

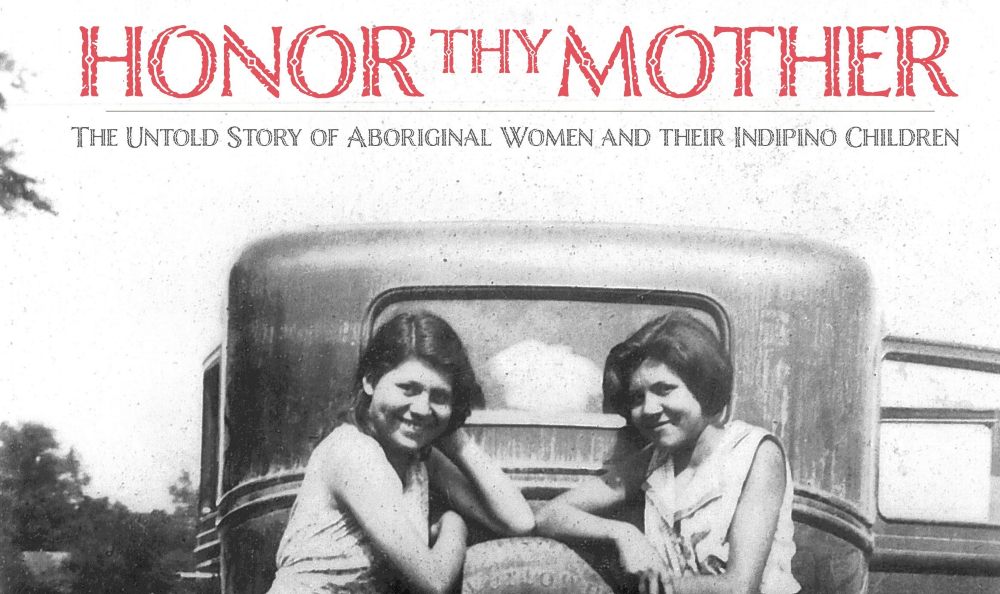

After she learned her mother’s story, Corpuz determined to share it with others and help educate them about “the hidden history of Bainbridge Island.” She celebrates that story in the new short documentary, “Honor Thy Mother.”

“Honor Thy Mother” is produced and directed by Bainbridge Island resident Lucy Ostrander of Stourwater Pictures, who specializes in filming historical and social issues. Corpuz is the film’s executive director. The 31-minute film took two years to make and is a selection of the Social Justice Film Festival, Local Sightings Film Festival, and film festivals in Tacoma, Bend, and Friday Harbor among others. There are several screenings in coming weeks.

The film tells how Corpuz’s mother and 35 other women from 19 different tribes in Canada, Washington State, and Alaska migrated to Bainbridge Island in the late 1930s and early 1940s to pick berries for Japanese American farmers. The young women, many of them still teenagers, met and married Filipino immigrant bachelors who also had immigrated to work on the island’s farms. The film includes accounts from several children of those unions who describe the struggles they faced growing up part Filipino and part Native, of not belonging fully to one or the other community, and also of being rejected by the White community on Bainbridge. One man interviewed for the film talks about being “looked at as scum of the earth.”

“My goal,” Corpuz says of the film, “is first and foremost to pay tribute to our Aboriginal mothers whose story has never been told and to honor them for working beside our fathers in the fields and facing a lot of racism and discrimination within our own community and from the White community.”

These Indipino children, like Corpuz, grew up immersed in Filipino culture with little to no knowledge of their mothers’ culture and heritage. Her father, Anacleto P. Corpuz, was one of the founders of the Filipino Community of Bainbridge Island and Vicinity. “We were raised as Filipinos,” says Corpuz. “We weren’t even made aware that we were tribal people until we were adults. We were not allowed to celebrate our native culture.”

Corpuz was five years old when her mother, Evelyn Williams Corpuz, left the family. As an adult, the daughter set out to learn more about her mother’s heritage. She went to Canada and met her Squamish Nation relatives and learned about the spiritual and traditional practices, the language, the sacred places and ceremonies.

She learned more about the heartbreaking years her mother and other First Nation children spent in Indian Residential Schools where they were not allowed to speak their own languages or practice their own culture and never received a real education. Much of the film focuses on the tragedy of those schools with grim accounts from Corpuz and five other adult children of the First Nation women who migrated to Bainbridge. Particularly moving is a first-person account by an elderly survivor about being taken from her family and sent to an Indian Residential School.

“Both the Canadian and U.S. governments passed legislation to steal children away from their families and place them in Indian Residential Schools from ages 5 to 15,” says Corpuz. “That in itself is an atrocity in the history of North American that most people don’t know about. To know you are a descendant of a child who was stolen from their family by the Canadian government is horrifying.”

Corpuz, a long-time social justice activist and retired educator, helped found the non-profit Indipinos of Bainbridge Island and Vicinity and remains an active member of the Filipino-American Community organization.

The Indipinos interviewed in the film describe how as children some in the Filipino community shunned them for being half First Nation while their White neighbors often discriminated against them for being Asian. Following the forcible removal of the island’s Japanese Americans to internment camps during World War II, Corpuz says the Filipino community purposely kept a low profile out of fear that they too might face internment.

“We had to be quiet,” recalls Corpuz. “If anybody was bullied on the playground, called names, if teachers used racist words in the classroom, we were not allowed to protest because we might be next, we might be marched on to the ferry to take away to a concentration camp.”

She believes “Honor Thy Mother” can help reduce prejudice and discrimination by celebrating biraciality and the resiliency of their community. She hopes to make it available as widely as possible to educators to share with students and also has developed an Indipino Traveling Historical Exhibit with the Kitsap Historical Museum that can be used in classrooms and libraries.

“It is so important for classroom teachers to show the history of indigenous and Asian immigrants and how these two communities came together through agriculture and how through their resilience and coping learned how to be a community that has been able to sustain itself,” says Corpuz. “It’s quite an emotional film. When an audience experiences strong emotions, it compels them to learn more. The more they know, they more they understand and the more they care.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“Honor They Mother” has been awarded the Special Jury Award for Indigenous Short at the Bend Film Festival.