In the Quincy, Washington cemetery lies a gravestone with the carved statement: “OKLAHOMA SLIM – PLAY THE HAND THAT IS DEALT YOU.” The dates are: 1914-1999. Slim, a.k.a. Albert W. Norman, “Caught the Westbound” (hobo vernacular for dying) after over 70 years on the American road. His life shed a lot of light on the world of hobos.

His home in Beverly, Washington, consisted of a refurbished railroad boxcar. A pot-bellied stove, kitchen table and black leather psychiatrist’s couch dominated the main room. Within a stone’s throw of his domicile is the Columbia River, and on the nearby high plateaus are acres of vineyards and cherry orchards. A path of the old Milwaukee Railroad crosses the river near Beverly, so Slim was never far from the noise and promise of a railroad. (Beverly, named by a V.P. of the Milwaukee RR for Beverly, Massachusetts, is a tiny burg near the Native site of Priest Rapids.)

At age eight, in 1922, after an abusive home life, Slim climbed aboard a freight train with several buddies. From that day forward Oklahoma Slim was a traveling man looking for work and adventure. Except for his last years in Beverly, he never had a family hearth. Hobo jungles, railroad yards, fruit orchards, patches of farmland, and the edges of hundreds of small towns were his “homes.”

One of his early freight train adventures took a bad turn. After escaping from a prison farm in the Old South with a buddy named Stub (for his missing finger) and laying low in a culvert, the sound of a train vibrated through the dark. He asked Stub if he knew how to hop a train. Stub assured him that he was an experienced traveler, but instead of grabbing the front of the moving car, he wheeled onto the back.

The train’s motion whirled Stub between the cars, cutting his leg off below the knee. Slim took off his belt to make a tourniquet and went for help. At a small nearby hospital, the admissions officer insisted on knowing who was going to pay for treatment. Slim’s words to the hospital staff: “Dammit, I say the man needs help now; we can fill out the form later.” They were ejected from the hospital.

Slim then sat Stub against the hospital front door and threw Stub’s severed leg down the hallway. He told the nurse, “If this man dies, I will charge you and this hospital with murder.” Stub received treatment, but lost his leg. Slim left the South and never returned. The Pacific Northwest beckoned.

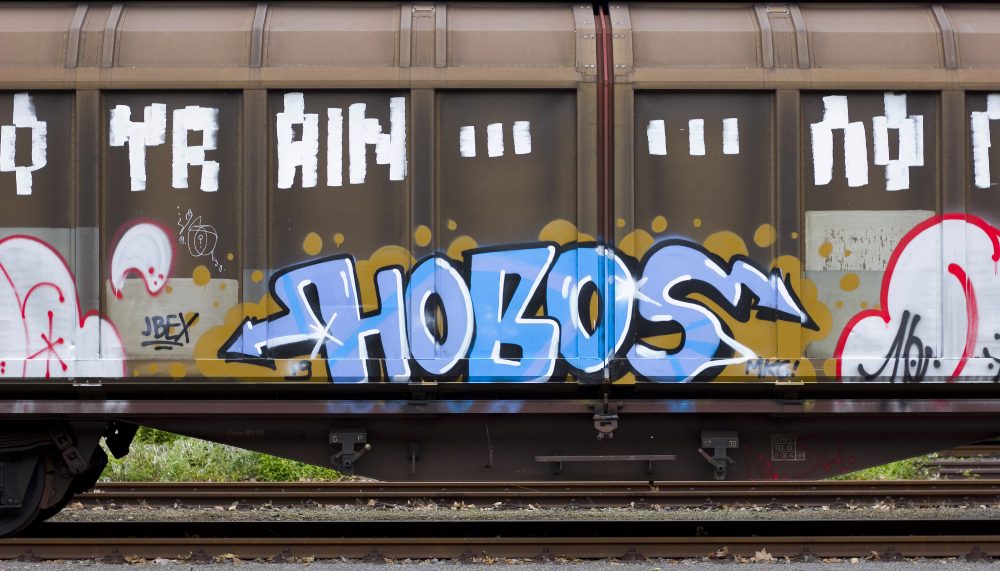

Slim wrote copiously. Besides a tidal wave of letters to friends and officials he cranked out an unpolished mimeographed newsletter, THE HOBO. This folksy sheet was mailed to his private list and left in laundromats, cafes, saloons, service stations, and post offices throughout the state of Washington.

Slim railed against bureaucracy, corruption, war, great wealth, and dishonesty. His single-page sheet included advice to “street kids,” with a toll-free number for help. Slim never ceased blasting private power companies, insisting that grand juries be called to investigate “the truth” of their nefarious activities. Another target was Hanford and its “toxic wastes” near his precious Columbia River.

In 1895 Slim took umbrage when he thought the F.B.I. was on his tail. He complained far and wide to no avail, which prompted the following statement in his newsletter:

“Things to forget. Forget the Governor’s Office. I was there. Forget the Legislators. I was there. Forget the State Attorney’s Office. I was there. Forget the F.B.I. I was there. Forget the Representatives in Washington. I was in contact with them.”

What or who is a hobo? H.L. Mencken’s The American Language gave it a shot. Wikipedia pulled together a wide collection of facts. A number of writers offered views: “Hobo,” by Eddy Joe Cotton; “Hard Travellin’,” by Kenneth Allsop; “The Hobo Handbook,” by Josh Mack: Seattleite Daniel Leen’s charming little book, “The Freighthoppers Manual.” Not to mention any song, poem, or line written by troubadour Woody Guthrie.

But Oklahoma Slim’s artless definition of “Hobo” takes first prize:

“In the beginning of this country there was a lot of single men, with no home and only a few bits of clothing, the only thing they owned was a hoe. They worked the farms and when the work was done on one farm, they would tie their little bundle of clothing to their hoe and move on.”

Slim expands his definition of hoboing with shards of homespun American history:

“The Civil War made thousands homeless . . . the thirties put millions on the road; there was two million riding the freights alone . . . the hobo world was swamped with hungry homeless people, most of them was Okies and Arkies, bible-thumping people, snuff-dipping women, tobacca-chewing men, convinced the Lord would look after them . . . I watched the American Legion wearing little blue hats and (holding) clubs come into the Jungles (hobo campsites) and beat hell out of the commies. For many years I thought a commie was a homeless person; at the time I could not understand how a war vet could beat another vet from the same war. I still don’t understand.”

Hood River Blackie, a contemporary of Slim’s, put it another way:

“No group in American history ever roamed as far across this great land as did the hobos, so let’s salute them just once as they follow the steam locomotive into history. Let’s remember them as they truly were the last pioneers; for when they are all gone – as soon they must be – this world will not see their like again.”

These authors and other former hobos quickly point out some class distinctions. A “Hobo” is NOT a “Tramp” or a “Bum.” Hobos are traveling workers, usually migratory and seeking farm work. A “Tramp” also roams the territory, but is rarely looking for work. A “Bum,” according to these experts, shirks work and has no particular destinations or projects in mind. Also, hoboing filled chapters in some notable American lives: musician Utah Phillips, prize fighter Jack Dempsey, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, writers Jack London and Louis L’Amour, and poet/historian Carl Sandburg.

More than 100 years ago a National Hobo Convention was held in Britt, Iowa. Smaller annual gatherings occur at Dunsmuir, California. At the town of Britt, which hosts the event, a parade (on flatbed trucks) is held, music and poetry fill the air, and a Hobo Queen and King are crowned.

“Road monikers” are periodically listed in the Hobo Times, a publication of the National Hobo Association in Los Angeles. Samples provided by Oklahoma Slim: former Seattle resident Fry Pan Jack, Guitar Whitey, Little Swede, Roundhead, Boxcar Myrtle, Flo Bo, and Jersey Red.

Economic and social conditions subsequently swallowed or obliterated Oklahoma Slim’s hobo world. Before Slim caught the Westbound he cited examples of the adverse changes. Freight-jumping today is more dangerous – the diesel locomotive moves swiftly. New trains offer few platforms or cubicles for a traveler (approximately 700 people a year die from railroad trespassing incidents). Many itinerant travelers are armed and sometimes one jump ahead of the law. Although the “bulls” (railyard police) don’t carry nightsticks anymore, they are aided by electronics and cameras.

Government programs to aid indigents and others have proliferated, including multi-layered services for the homeless. Add in welfare, subsidies, handouts, and brimming garbage cans with more usable waste. Farming has evolved, and machines (not hoes) plant and harvest many fruit and vegetable crops.

Slim’s health failed in his late 70s. Looking back on his life, he observed: “us old steamers . . . were going to be gone . . . we just got time to sit around, brag and lie a little bit. But the wanderlust is in everybody’s soul.”

He was ready for the Westbound. Contemplating his last trip, he described a hobo jungle in the sky, with his friends sitting around a campfire. His Quincy tombstone summed up his advice: “Play the Hand that is Dealt you.” When he died in 1999 Oklahoma Slim was confident that he had done and seen everything possible during his roaming, writing, talking, giving time on this fragile earth. As a hobo poem puts it:

“Who could have known so long ago

When I could barely walk the track

That I would someday feel and know

The rhythm of that click and clack.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks Julius! Really enjoyed the article. Something romantic about the Hobo life…and Slim’s!

Some things never change……..Great read

It suggests how rich was the environment supporting the poor, now sadly declined to homeless tents. First Avenue in Seattle used to be a good place to live in poverty: 5-cent beers, SRO flophouses, services, ways to get a job, hiring halls, cheap meals, missions and churches. Most of these things have been regulated away. As the article demonstrates, a whole vocabulary and set of customs arose around those who rode the rails and lugged a hoe.

What a glorious tribute to a fine storyteller!

Nice story !

Dear Junius,

A tale well told of a hard traveling working man. Times have changed utterly and the likes of Oklahoma Slim are now the stuff of history spiced with a sense of the open road and freedom, as well as hardscrabble living. Thanks for sharing this story!

Thank you for this. He was my husband’s Uncle. Sorry my husband never saw this. We went to see him in 1990 and and I video taped him telling some of his stories.

Thank u I remember hearing so many stories and actually reading some of his “hobo times” my dad talked of his uncle Oklahoma slim or uncle Al quite a lot growing up. Wish id have met him. But though stories and slides. I feel as though I did a lil bit

I just came across this article and was surprised that it was about Beverly, WA and Quincy, WA. My parents, Eugene & Fannie Burkett, are buried in Quincy. They lived just up above Beverly. My dad bought the property back in the early 70’s and lived there until he died in 1983. My mom continued to live there until she got cancer & had to move in with family in Idaho where she died in 2001. The property was sold to P. U.D. and is now named Burkett Lake Recreational Area as a legacy to my parents. They moved there in 1973-1974 moving bringing electricity to the property & a well. Built up an orchard. Later on P.U.D. created a lake on part of the property. My dad sold off almost all the property to others who moved there. I used to take my kids to visit every summer from the Puyallup/Tacoma area. My mom & dad were from Okmulgee, OK. My mom told me stories of meeting hobos.