David Michaelis, author of the new biography, Eleanor, met the admired humanitarian when he was just four and his mother was working on an installment of “Prospects of Mankind,” Eleanor Roosevelt’s TV program. Michaelis recalls, “Like practically everyone else, I asked Mrs. Roosevelt for something.”

The four-year-old David breathed out two words, “Juicy Fruit.” What she gave him in return was a luminous toothy smile and a noticing gaze “One so full of goodwill it seemed to brim out of her eyes like light.”

The author not only remembered that moment but honored it by spending a decade producing this cradle-to-grave 700-page account of Eleanor Roosevelt’s event-filled life. He depicts her not as a partner to Franklin Roosevelt (which she was), but as her own person — the people’s proxy in the White House, the architect of international human rights, and world citizen.

His book is the first major single-volume biography in half a century, a resource for people who want to know more about the nation’s longest-serving First Lady and “First Among First Ladies.. When recalling the New Deal, most sources credit Franklin, but it was Eleanor who pushed for women’s rights, civil rights, and programs to get the nation out of the Great Depression. It was Eleanor who travelled the country to learn how best to help depressed communities.

Michaelis’ biography starts with a helpful list of main actors. Otherwise it would be difficult to tell the Annas, Elliotts, Alices, and Teds from one another, nor to identify them by their relationships and nicknames like Aunt Pussie, Uncle Vallie, and Cousin Ted, better known as Eleanor’s Uncle Theodore Roosevelt.

Eleanor started with a dismal childhood, ignored by a mother who mocked her looks and seldom attended by a father deep in alcoholism and seldom there. Orphaned before her teens, she went to live with her Grandmother Hall. She had to fend for herself, washing up after her aunt’s parties and installing triple locks in her bedroom to thwart lecherous uncles. Her grandmother, noticing Eleanor growing wan and chalky, enrolled her at Allenwood, a London boarding school where she conversed in French and, on holiday, travelled with the independent-minded head mistress, Marie Souvestre.

Returning home after graduation and forced into “coming out” as a debutante, she compensated by throwing herself into the settlement house movement, tending to the poor. It was then that she became reacquainted with Franklin, her attractive and frankly ambitious fifth cousin.

Engaged to marry, Eleanor had to be approved by Sara Delano Roosevelt, Franklin’s dominating mother. During the long engagement Sara demanded, Eleanor had agonized to a cousin, “I shall never be able to hold him, he is so attractive.” They married in 1905, with Uncle Ted showing up to walk Eleanor down the aisle.

Their semi-royal European honeymoon was scarcely a success. Franklin had attacks of painful hives and he failed to make Eleanor, never a beauty at almost six feet and bucktoothed, feel truly lovable. She found the sexual side of their marriage less than pleasant and thought he did as well. All his life, those closest to Franklin concluded he was “completely impenetrable” when it came to his inner feelings.

Eleanor quickly gave birth to six children (five survived). Then during Franklin’s wartime service as assistant secretary of the Navy, she discovered his affair with Lucy Rutherford, her attractive young secretary. Although willing to give Franklin his freedom, Eleanor stayed on, convinced by advisers that Franklin’s political career would be destroyed by divorce. From then on, the marriage, which had not worked out well in private, evolved into an effective political partnership.

Michaelis doesn’t hesitate to address Franklin’s and Eleanor’s subsequent romantic lives. In Eleanor’s case that involved close women friends and younger men. But the pairings, according to the author, were mainly unconsummated crushes. Franklin, however, maintained relationships with Marguerite (Missy) Lehand, his cousin Margaret (Daisy) Suckley, and others, including Lucy Rutherford.

Eleanor came more into her own after Franklin’s 1921 Polio attack. She supervised his care and may have saved his life, helping him return to the national stage. Incredibly he was able to resume his career, first as New York governor and then as four-term president.

Although a powerful team, the Roosevelts often differed on critical political issues. She opposed Franklin’s failure to support significant racial and relief initiatives and his unconscionable decision not to allow entry to Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazi regime. From D-Day on, she spoke against internment of Japanese citizens. However, Michaelis does point out some of the areas, among them women’s suffrage and early anti-semitism, where Eleanor had not been ahead of her time. Ultimately, she evolved way ahead of most of the nation.

In 1943, the indefatigable Eleanor insisted on going to the Pacific war zone to support the troops. When asked if the trip wouldn’t leave her exhausted, Franklin said, “No, but she will tire everyone else.” Facing the challenge, Eleanor rose at 5 a.m to breakfast with enlisted men, visited hospitals and fighting units and, according to at-first skeptical commanders, accomplished “more good than any group that passed through.”

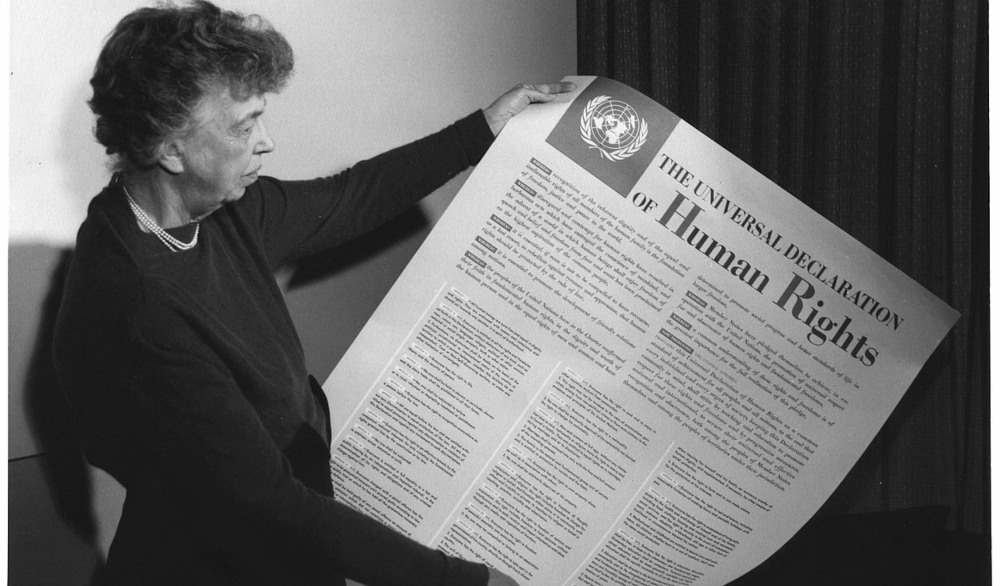

Following Franklin’s death in 1945, President Harry Truman appointed Eleanor to a high-profile job in the new United Nations General Assembly. Her goal was the hard-fought but ultimately successful adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, pledging to honor social, political, religious and economic rights. After the vote, she received a never-before-given standing ovation.

Michaelis included an immense amount of detail and painstaking scholarship in his mega-biography, but unfortunately he did miss an opportunity to touch on Eleanor’s Seattle connections.

Family ties initially brought Eleanor to Seattle. Anna, her only daughter, and her husband John Boettiger lived and worked here after he was appointed Seattle Post-Intelligencer publisher in the mid 1930s. Anna served as the paper’s Women’s Page editor. The couple’s son John was born here in 1939. Whenever in Seattle, Eleanor used the P-I offices to write “My Day,” her daily newspaper column, distributed across the country. (Before her final illness, she would write more than 8,000 columns.)

Later, in 1953, Eleanor hired Pat Baillargeon, a Seattleite from a prominent banking family, as her secretary and special assistant. Interviewed in a 2016 documentary by Discovery Institute’s Bruce Chapman, Pat recalled the seven years the two spent together. Eleanor had lost her United Nations post when Eisenhower became president but, never daunted, continued as an unpaid volunteer for the American Association for the United Nations. She kept a busy schedule giving speeches, doing radio and TV, and promoting human rights and world peace.

Speaking with Chapman in 2016, Pat vividly recalled working with Eleanor. She said, “We had a small office in New York City, two desks pulled together. Each day, Mrs. Roosevelt fielded the great stacks of mail, every piece answered.” The two travelled and visited every state, some more than once. Eleanor refused any special benefits, aside from a franking privilege. Baillargeon explained, “She would dictate the column and then I would call it into Western Union for distribution across the nation.” Eleanor took no pay but accepted membership in the American Newspaper Guild.

Afterward, Pat returned to work on Seattle projects (the World’s Fair, open housing, and the Port). She passed away last year, but her memories are still available on line through Discovery Institute. Like Michaelis’ book, they are a way to celebrate one of this nation’s and the world’s most extraordinary women. Harry Truman had rightly called her “the First Lady of the World.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A nice column and a Fantastic women! Will there ever be a first “whatever” to rival her?!