Protestors filled the streets of downtown Seattle on Saturday, May 30, 2020. They came for a rally at noon. They stayed for a rally at three. Their numbers grew all day long. And they stayed some more. They came to protest yet another instance of police brutality against a black man—a literal murder caught on cell phone video—the archetypal image of the white man’s foot on the black man’s neck having come true, a white officer pinning down a black man and squeezing the life out of him with his knee.

After the speeches ended, rather than disperse and shrink, the crowd grew. It grew out from the Westlake Center plaza and into the streets with trendy upscale stores spreading out along the avenues. The rallies were over; it seemed that no one had left.

Suddenly Molotov cocktails were flung into police cars, which burst into flames. Baseball bats broke car windows. Protestors yelled slogans through their masks: No Justice! No peace! Part of the crowd, a hundred people or more, spilled onto the freeway, shutting Interstate-5 down. Black lives are under attack! Whadda we do?

The presentiment of possible looting was pushed through the tear gas filled air. Stand up! Fight back! Water and milk were poured into streaming eyes. Black lives matter! The crowd was too dense for the fire fighters to reach the flaming vehicles. The smoke billowed from flames and teargas. I can’t breathe! Chaos burst into the open. It was only 4:45 pm. Broad daylight. Barely evening. Nevertheless, the mayor declared a curfew would begin shortly. And sure enough, cell phones all over the city of Seattle soon buzzed and shrieked, ordering everyone to retreat to their homes. Hands up! Don’t shoot! It was 5 pm.

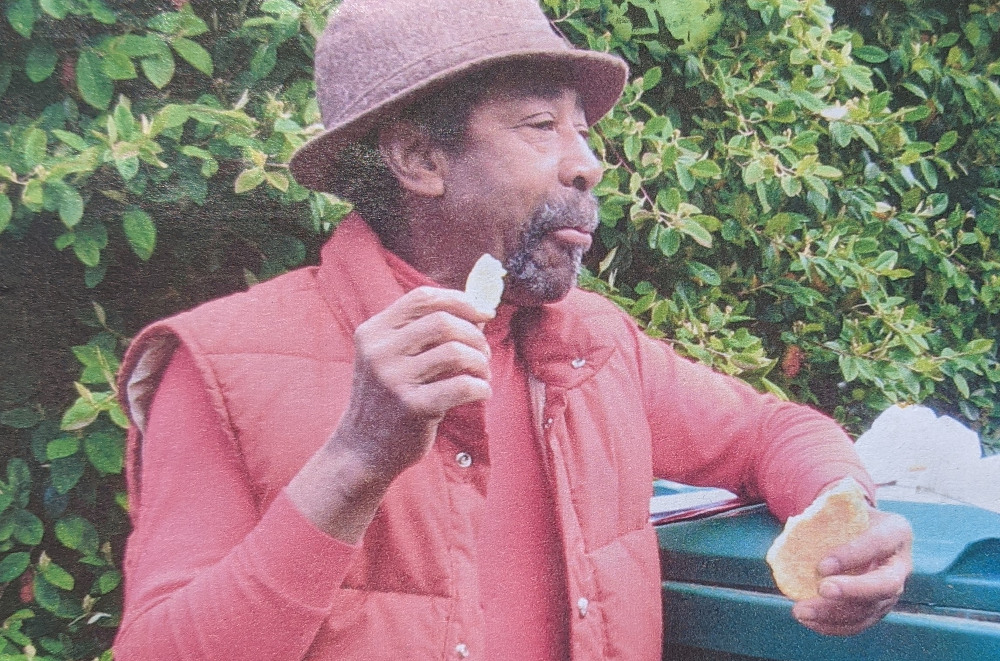

But Lazaro did not have a cell phone. Lazaro was six miles from the unrest. I wish he had been there, for the protests were for him too. His seventy-nine-year-old black life still mattered.

The day before, he had received his pitiful weekly stipend of $75, doled out by his state-appointed guardian. He had pocketed the full amount at his bank–’’La Chásay’’ he called it, otherwise known as Chase. And on Saturday as the protests grew in volume and violence, he left his low-income apartment, padded off to his favorite little bodega on Market Street, and bought a six-pack of Corona, or was it two? He did have people who cared about him, neighbors in his low-income housing building, but no one he could really hang out with. Or rather, no one who would invite him into their own apartments.

Lazaro had come a long way since he left the port of Mariel, Cuba, in 1980. And yet his life had been lived on the margins ever since landing in Key West on that hopeful May day. A few beers into the evening as it slid by, he took one (or was it two?) in a brown paper bag and shuffled off for the little neighborhood square in Ballard, only a couple of blocks from his home. The square was an American version of the plazas Lazaro had known so well in Havana. The gathering place for all, hang-out central. He instinctively made for the Ballard Commons.

He headed there also because this is where he had people to hang with, though I hesitate to call them friends, for he was always an easy mark. The worst of them stole from Lazaro, a few saw him as a possible provider of an indoor place to sleep for the night and pawed at him with their self-serving attention, but mostly, they were people to hang with, the down and out of the neighborhood. The friendless. His only friends. They greeted each other, they connected.

Gradually in the past year or two, the Commons had become ringed by the cars and vans of people for which this was their last possession—the people parked permanently. Lately, more and more tents had joined the cars—tents on the sidewalks, on the Commons’ grounds, in front of the church, the library, with its bathrooms open to the homeless. These people always, well, more often than not, greeted Lazaro in a friendly manner, looking for a beer or a buck that was straggling out of his pocket, as often as not. And some would offer him a joint, less often and sometimes not.

As COVID-fears proliferated, the encampment grew throughout March and April. The library, with its bathrooms and shelter from storms, was shuttered. The church closed its doors. Does the Episcopal Church still welcome you? But tents and tarps were everywhere. It became difficult to traverse the sidewalk. The rubbish grew also. And the complaints.

And so on May 4th the city government moved in and cleared out the encampment at the Ballard Commons, forcing the tents down, offering limited shelter to the displaced, which some accepted. Most moved on to some other spot, where they would remain briefly, before it, too, would be cleared out, pushing the people along, the lives that didn’t matter enough to have a place to go to.

On this Saturday night, with the protests turning to riots only six miles away, Lazaro wandered through the drizzle and the downpours into an empty, wet plaza with his beers and his bag. A lone shopping cart lay on its side, its contents—a blanket or two—drooping out. The row of young Aspen trees bordered one side of the skate-board park. Maybe someone stepped off the concrete, flicking up his board into his hand, maybe not. Maybe someone nodded hello, but probably not. At the far corner, one small tent had crept in on the edge. How long Lazaro sat alone on this eve of destruction, I do not know. He rose finally, his brown eyes filled with loneliness, and turning, trudged towards home as he had done after so many previous midnights. And he stumbled, as he had stumbled so many times before, this time alone. He fell face down and he did not get up.

Say His Name: Lazaro Casamayor Pineda. December 17, 1940–May 30, 2020

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Heartbreaking. Thank you.

Thank you for this update. I still would wonder about Lazaro on occasion. I can stop now.

Peter

Very touching

Nice writing and a moving, eloquent statement.

Such a compelling narrative. Thank you!

Thank you for telling his story! Beautifully written❤️

???

This gives such great insight. Thank you.

Speaks strongly for others besides Lazaro. Good writing.

Very moving and beautifully written

Well written story. Thank you.

“The people parked permanently.” How true. And how many people has this country forced to park permanently, or worse. You created a sharp and vivid window into something we can’t become comfortable with, but we have anyway. What does this say about us? Thank you for sharing this.

Cuban guy Lazaro’s sad life … in the protestants. I wonder the Lazaro’s whole life. Can I expect next story?