JS Bach’s Goldberg Variations are an unlikely musical icon. For one thing, they lack an iconic tune to take home in your gift bag. The theme hangs in the air as if it’s uncertain when and where it wants to come down. The piece – a theme and thirty variations – is also long. There are repeats everywhere, and depending which ones you take, a performance can last 40+ to 70+ minutes.

The Goldbergs might be the perfect piece for the fog of a pandemic. At its most languorous it exudes inevitability – dreamy and wandery even, but always kept on the path by a pulse which is not so much heard as felt. In the faster variations the pulse is spikier, jutting out propulsively to pull you along, an entirely different kind of inevitable. The point is, you have to surrender to it, whether to the slow or fast, and at the end of each variation it all works itself out satisfactorily. By the end of 30 variations – 30 versions of how it all works out satisfactorily – you’re reassured about the order of the universe. Who doesn’t need that in these trying days?

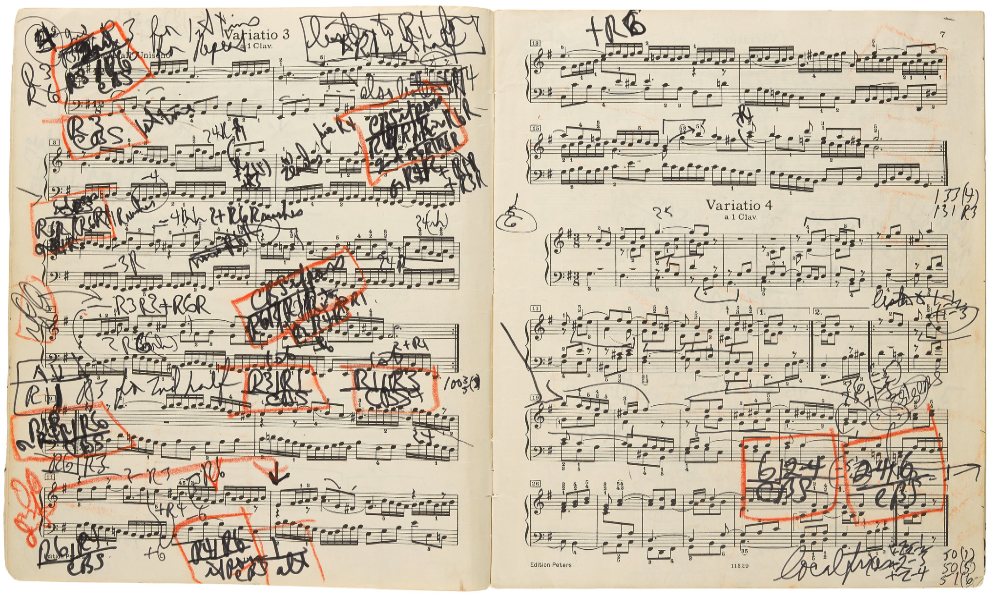

The score itself is a treasure map of sorts – the basic notes are all there (although the extensive ornamentation is up to the performer), but there are no indications of speed or dynamics or phrases or attitude, leaving it up to the performer to make of it as they will. Back in Bach’s time, performers would have understood his intentions by way of conventions of the day. Today, Bach’s outline is up for debate. For one thing, the Goldbergs were written for the harpsichord; today it’s more often performed on the modern piano, which though it has a similar configuration of keys, has an entirely different soul.

The differences between plucking strings (on a harpsichord) and hitting them (on the piano) is vast. Plucked strings vibrate until they die and phrases are shaped by their structural momentum; hit strings can be dampened and shaped, you can strike them with percussive force or gently coax out the sound. Musical lines are shaped as much by the color of the sound as by their melodic or harmonic structures.

So the performer has some decisions to make about how to approach these notes – most calibrate somewhere between harpsichord and the modern piano machine. Or, you can do as Lang Lang does in a new recording just released, and go full piano pedal to the metal.

Were you to have asked about my interest in a Lang Lang performance of the Goldbergs I would have passed, maybe with even an involuntary shudder. Arguably there’s no bigger box office attraction in classical music right now than Lang Lang. He’s one of the few artists who can dependably sell out a hall, but he’s also an emotive showboat. Not that I’m against showboating, but, blessed with seemingly effortless ability to do whatever he wants on a keyboard, Lang Lang rarely passes up the opportunity to set the emote dial to 11. Sometimes (often, even) it’s thrilling, but it also gets predictable, and all the sincere emoting seems ultimately… well, insincere. Cheap.

He said in an interview on NPR last week that he regarded the fast variations of the Goldbergs as easy exercises, not much of a challenge for his fingers. He plays them at breakneck speed, spinning off notes with precision and velocity that no harpsichord could match. While it’s certainly thrilling and virtuosic – on the harpsichord it would be little more than sound mush – it occasionally feels careless or skipped over. He does, however, intriguingly highlight voices in unexpected ways and emphasize notes that make your ears reconsider the musical architecture.

Though the Goldbergs are held up as one of the most important examples of the theme-and-variations form, to me they’ve always read more as a series of meditations and refutations, the theme not so much a literal statement to be variationed with, but inspiration for theme-adjacent fun. The main thread is tough to cuddle up to; just when you start to get comfortable, there’s a jarring chromatic smudge or detour that seems out of place, and the many virtuosic interruptions can seem calorie-free as they go running by unimpeded by gravity.

It’s the slow parts that get Lang Lang’s attention. He plays them as slow sprawling quasi-improvisations heavy with rubato, as if he’s trying in the moment to work out what the next notes should be. And yet, his ability to convey the inevitability of those notes even as he makes them so elastic they threaten to break, is deeply affecting. This is surely the most pianistic version yet recorded. Lang Lang takes repeats, but he also draws out the slow parts so much that the performance clocks in at a colossal 91 minutes.

The Goldbergs have been recorded hundreds of times, but the most famous was Glenn Gould’s austerely brilliant 1955 recording when he was 25 and which helped launch his career and make him a legend. At the time the piece had been considered a bit of an esoteric academic piece, but Gould romped through it, bringing a pianistic sensibility and color that at the time seemed modern, audacious and absolutely right.

Listening to it again now, it seems straight, crystalline and rigorous, the voices and counterpoint interacting in perfect clarity. Gould gave the voices a shape and intellectual oomph in a modern, pianistic way in which voices in the counterpoint scrolled out with their own independent intentions. Phrases peaked and resolved in the ways a modern piano could but a harpsichord, with its plucked strings, could not. His 1981 recording, a year before he died at age 50, bookended his thinking, and it’s a warmer, more complex performance that nonetheless retained the clarity of the original. Gould, ever the iconoclast, disavowed his first recording for the second.

Since Gould, the Goldbergs have been recorded dozens and dozens of times. They are a great vessel for the musical sensibilities of the day in which they’re being performed. Gould’s original was a sensation because he made you hear them as piano pieces, doing things only a piano can. It was as if he had suddenly shifted the gravity of how we regarded Baroque keyboard music. At a time when atonal experimentation in the very building blocks and rules of composition was at full mast and Romanticism in retreat, Gould’s Goldbergs personified the spirit of exuberant expression. Later, the Early Music movement in honoring original performance practice found plenty of pianists happy to demonstrate the principle with the Goldbergs.

More recently, however – perhaps the past ten years or so – a new generation of musicians, many of them European or Asian rather than American, and seemingly immune to challenges of technical difficulty, have begun to experiment with highly personal and original interpretations of traditional repertoire. Whereas the era immediately preceding them prized technical brilliance that often led to more conventionally narrow interpretations, the new generation – freed from worries about technique — have put more or less everything else on the table for rethinking.

Musicians such as Moldovan violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja, Swedish clarinetist Martin Frost, American flutist Claire Chase, Russian-American pianist Kirill Gerstein, Greek conductor Teodor Currentzis, and many more are rethinking the repertoire in the context of today. That means something different to each of them, but these are all musicians steeped in the culture of today, a time when genres across the culture are being blurred and ideas in popular culture are constantly interacting. This is also a time where being an artist and interacting with an audience means something different than it did even ten years ago. True originality is prized in a networked culture.

Oddly – because he’s more or less of the same generation as those I just mentioned – Lang Lang almost seems like an older, more transitional figure than the others, probably because he shot to fame so much earlier than the rest. He revels in transcendent technique, while the others take their own for granted and move on, and his version of originality has not seemed so interesting as these others until now.

These new Goldbergs, however, are terrific, as compelling musically as they are pianistically. While it’s dangerous to compare this to something as iconic and groundbreaking as the Gould recording, Lang Lang puts a fresh stake in the ground for a new generation of pianists.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A wonderful analysis not just of the Lang Lang performance but also of the piece itself and of the relation between modern culture and performance style. Also of great interest is this new stage in the remarkable spread of central European music and its performance into other continents. Glenn Gould’s Goldberg performance was evidence that North America had become a valid and interesting new home for interpretation of iconic European musical classics. And now Lang Lang does the same for Asia, reinforcing the remarkable contribution of Japanese, Chinese and Korean performers of the European classics.

Yes, this is a prime time to get some reassurance about the order of the universe. Thanks for the encouragement to try this new recording. Or to listen to the earlier ones.