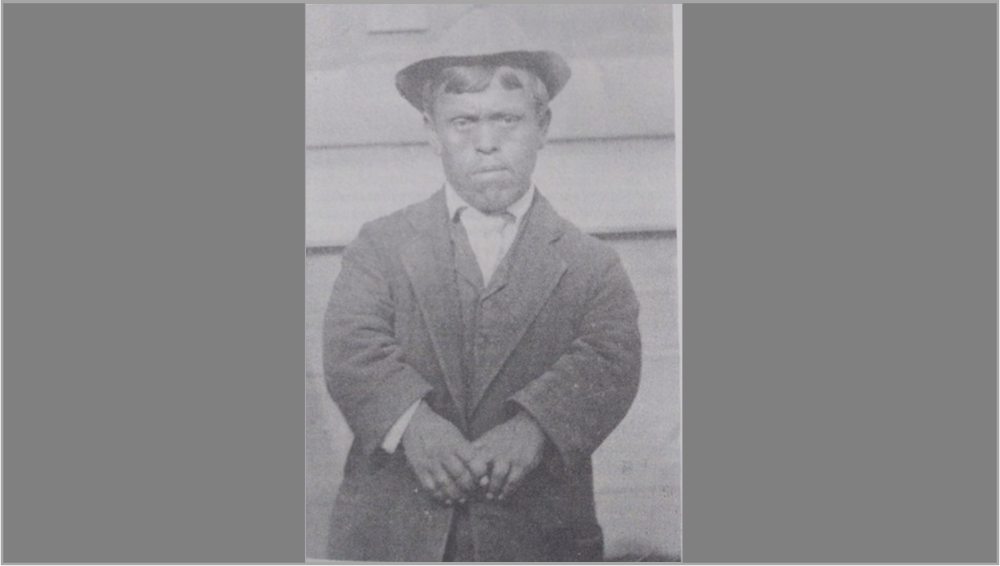

The following is an adapted excerpt from “The Burning of Moses Seattle,” a book about the murder of Chief Seattle’s dwarf grandson, Moses Seattle.

Long after most of Chief Seattle’s people were forced onto reservations, his daughter, Princess Angeline, continued to live on the Seattle waterfront in the town named after the chief. She supported herself and her grandson by weaving baskets and cleaning clothes.

One of the greatest mysteries about Angeline was her odd devotion to laundry. She worked as a laundry woman for the Bagleys, the Fryes, and all the other elite white families of early Seattle. What the whites viewed as drudgery, she undertook with a religious intensity that nobody understood.

Historian Clarence Bagley remembered that if you irritated Angeline while she was washing clothes she would “take her hands out of the water, grab her hat and leave the premises in high indignation, not waiting for leave-taking or even her pay.” Rev. Atwood respected the way Angeline “presided with queenly grace at the wash tub in the parsonage kitchen.” To let her wash clothes in peace, Rev. Atwood had his young son stand by the door to steer people away from walking in on her. Posting a guard also irritated Angeline.

Her mild irritation at having a guard was nothing compared to her rage if somebody just barged in. Rev. Atwood’s fellow preacher, R.W. Summers, could hear her screaming

in Lushootseed. Her curses echoed out from the laundry room, filling the entire church.

With “eyes aflame and violent stamping,” Angeline stood in front of her washtubs, cursing out a whole group of white women who had dared to interrupt her during the sacred act of laundry.

Why such rage? Indians never directly explained things when talking about spiritual matters. Explaining the meaning of the old legends, or asking questions about them, was beyond taboo. According to Rev. Atwood, if you asked her about Christianity, Angeline would not respond with words. Instead, Rev. Atwood said she would “close her eyes, lay her head to one side and point upward.” It was her way of indicating she knew Christianity meant she would go to heaven instead of being reincarnated.

She was Christian but Indian-Christian. For people like Princess Angeline, Chief Seattle, or Chief Jacob, instead of saying they converted to Christianity, it would be more accurate to say they added Christianity, and Angeline added Christianity into the old teachings.

One day, Angeline took her silver dollars and was angrily leaving when she spotted a large map of Puget Sound on the wall. The sight of the map calmed her. Walking over to it, she pointed out all the lands her father was war chief over. Angeline suddenly switched

languages when talking about her father, speaking in English so everybody could understand. “He had much mountain land and many valleys and lakes: all these, here and here and here,” she traced her finger across the map. “And he had villages on the rivers and villages by the sea.”

Finally, she came to the last spot on the map she wanted to point out. “This was his village; this was his home.” The spot underneath Angeline’s finger — Chief Seattle’s hometown of Flea House — got the name Flea House because it was originally inhabited by a race of vampires. “Long ago in mythical time the people who lived here were very dangerous. They were the Flea-people,” the 19th century Duwamish elder Mary Jerry revealed. “They used to kill people. They were very large, as big as cougars are.”

The foundational myth of Chief Seattle’s hometown explained why cleaning is exactly like slaying vampires. If you get bit by an infected flea because you have dirty clothes, or a dirty house, you’re still going to die just like you would from a vampire bite. In the old Indian cosmology nothing can be created, or destroyed. Everything that has ever existed will always exist. Things just change size.

Elk Woman had made the vampires smaller. It was up to all of her descendants, all the way down to Angeline, to keep them away. They could not be defeated, only kept at bay, through constant ritualistic cleaning. When the cloud of death returned to Flea House millennia later, the attackers were smaller than fleas, smaller than the legs of fleas, smaller than bacteria. They were of the smallest units of life possible: little smallpox

viruses 350 nanometers across.

Flea House’s neighboring, much wealthier, town of Log Jam was hit especially hard. The town got its name from a huge log jam filling up the White River for over a mile. The clog of logs was so thick, smaller trees and bushes grew from it, creating its own ecosystem. The people of Log Jam loved the blockage because it forced river travelers to stop over in their town, making it a prosperous center for trade. The same conditions which made Log Jam great for trade also made it an epicenter for smallpox.

When travelers bumping into the jam found themselves forced to lift their canoes out onto shore, and pay tribute to the Log Jam people for crossing through their land, they also spread disease. Log Jam Jack, a Duwamish informant of the writer Arthur Ballard, said that before he was born the smallpox outbreak was so bad that the survivors had to bury the dead in a mass grave. The whites later built a town over the grave. Log Jam Jack did not reveal where.

The people of Log Jam used to look down on Flea House. The richer Log Jam elite could afford to wrap themselves in beautiful white blankets, woven from the hair of the now extinct Salish Wool Dogs. “They were white and fluffy,” the Snohomish elder Harriette Shelton said about the dogs. Princess Angeline’s grandmother watched those prized dog hair blankets go from status symbols to carriers of death.

Indian women found nothing servile about cleaning. Harriette Shelton said all upper class Indian ladies of her mother’s generation, or older, practiced zen-like cleanliness, seemingly doing little else.

Later in life Harriette Shelton had to work as a cleaning woman to support her family. She earned between seventy-five cents to one dollar a day (this was in the 1930s, not the 1880s. It would not have been a lot of money even in the 1880s).

“Now you clean that up good!” white women yelled at her as she scrubbed on her knees. Harriette said white attitudes towards cleaning always made her feel like she was back in boarding school.

In her grandmother’s time, a cleaning woman would not have been looked down on any more than a warrior. The Ska-lal-a-toots often gave men and women different versions of the same power, cleaning being a version of warfare going all the back to Elk Woman slaying vampires. The Indians were more right about the connection than they knew. Every major war of the 19th century had more deaths from disease than from combat.

The smallpox survivor Dr. Richard Gatling invented the first machine gun during the Civil War to save lives by requiring less soldiers, and thus less people in close proximity spreading disease. “It occurred to me that if I could invent a machine gun which could by its rapidity of fire, enable one man to do as much battle duty as a hundred, that it would, to a large extent supersede the necessity of large armies, and consequently, exposure to battle and disease would be greatly diminished.”

For Angeline, keeping the Duwamish homeland clean was an endless, losing, battle. “The early miners were proud of their long dirty beards and hair, their unwashed hides and patched pants,” wrote the Seattle reporter Thomas Prosch.

“Troubled with fleas, eh?” a man asked, watching a Seattle miner scratching himself all over. “Fleas, no.” Little parasitic blood sucking bugs crawled all over him.

“Do you think I am a damned dog, to be troubled with fleas? These are lice, these are!” Pride in filth was especially unique to Seattle. When a local merchant went only as far south as Oregon, a Portland barber was grossed out by how grungy he was. The strands of the white Seattleite’s long dreaded hair were like “the rungs of a ladder.” The barber begged him to cut it all off, but the Seattleite told him he grew it like a ladder “so that the lice could climb up and down.”

Seattle town founder, Dr. Maynard, was regarded as dainty for his habit of bathing once a week and washing his hands and face every day. To the pioneers, the Indians seemed like clean freaks. An early Seattle settler freezing his way through a northwest winter was shocked to see an Indian punch a hole in the ice of a frozen lake, jump in, and start scrubbing himself. William Shelton wrote that an Indian would bath in ice “until his flesh stopped tingling; this toughened the flesh and bodily cuts and scratches were less likely to become infected.”

When Princess Angeline still lived at Old Man House, she woke up every morning to the sound of the oldest man in the tribe walking the length of the house, banging on the walls with a stick. It meant it was time for everybody to get up and bath. Whether you were a High Blood in the upper bunks, or a slave in the lower bunks. Whether it was freezing, windy, hot, or hailing. Men and boys bathed in the salt water, women and girls bathed in the creek. Every single person. Every day. No exceptions.

Harriette Shelton was offended to meet old white women at the Seattle Historical Society who thought Angeline was “dirty.” Partially, they thought she was dirty because everything in Angeline’s cabin was covered in piles of ash from her fireplace. The white women didn’t know that Angeline covered everything in wood ash because it’s a natural bug repellant, keeping away fleas and lice. She also covered her walking stick in ash, using it to pick up things she found in the street so she didn’t have to touch anything in a town that had gotten so filthy and vampire infested.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This is a fascinating and important piece of local history. I had seen the name “Princess Angeline” on streets and buildings but never knew the full, poignant story of her life as Chief Seattle’s daughter, navigating the catastrophic changes to her people and her home. The details about her persistence in staying in her homeland, her work, and how she became a figure both visible and yet overlooked by the growing city are incredibly moving.

One thing that really struck me was the mention of the several portraits and photographs taken of her. For those who have looked into this more, is there a sense of whether she had any agency or specific intention in how she presented herself for those images? Or were they primarily projections and interpretations by the photographers and settlers who saw her as a kind of “noble relic”?

Hey Christine! I am the author of the book that this is an excerpt from. The reason there are so many photos of Princess Angeline is because she was apparently the only Native woman of her generation who actually enjoyed photography. According to people who knew her, she would laugh while looking at pictures of herself, amused by the novelty of it. The photographer Edward Curtis wrote that Angeline told him she far preferred posing for photographs to digging clams.

Excellent story about Chief Sealth’s (Seattle) daughter. I remember meeting Harriett Shelton many years ago while working on a documentary, “The Fishing People”, which tells the story of Tulip Indian fishing. She was a proud and important figure amongst the Tulalip people.

I read the book last night and found it to be exploitive of the indigenous Duwamish. It was interesting and I appreciate the efforts of the author. I mean no disrespect.