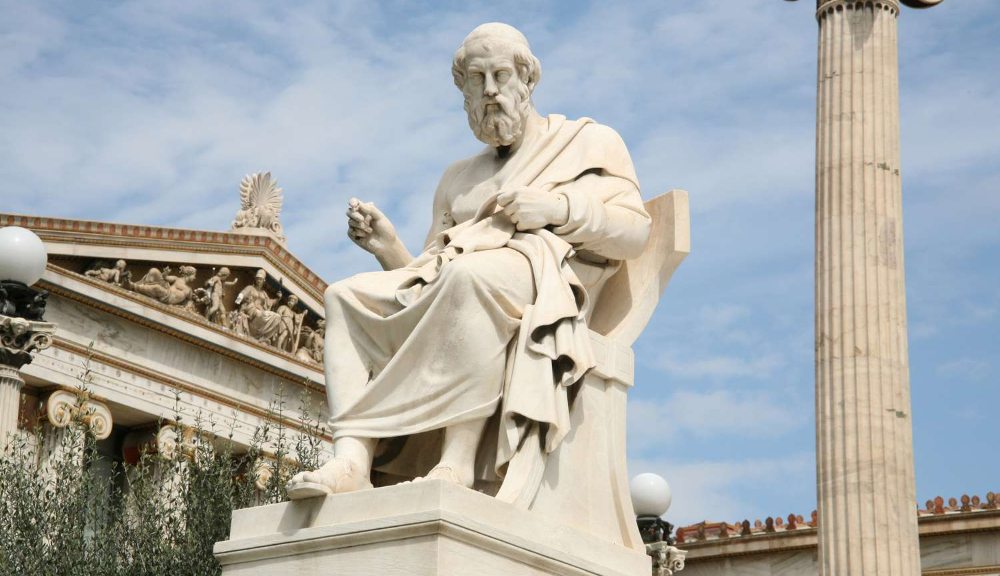

In a surprising consequence of new rules in the Texas state university system — rules that restrict the discussion of topics related to sexual orientation and gender identity — Texas A&M philosophy professor Martin Peterson was advised by his department chair that removing readings by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato from his course syllabus

would help in complying with those rules.

“A philosophy professor who is not allowed to teach Plato?” Peterson later told an interviewer, “What kind of university is that?”

Indeed, a new level of absurdity seems to have been achieved in the Peterson case

because Plato is normally considered, especially by conservatives, to be a foundational

wisdom figure for Western culture. The case also reminds us that Plato was

controversial in his day and is sometimes even more so in ours.

As a young man, Plato was captivated by the dialogical style of his mentor, Socrates, a

devotee of the oral tradition who never wrote or published his ideas. Socrates had found

a way to use the techniques of debate to pursue a kind of open-ended inquiry. Normally

debaters put forth their arguments in order to win the debate, but in Socrates’ method,

which is called “dialectic,” the participants use arguments and reasoned objections to

help each other seek the truth together.

The point is not to win a debate but to correct and be corrected, testing every argument that arises in a shared effort. A true friend, Socrates believed, was someone who would refute him when his reasoning was flawed.

The writings of Plato recreate Socratic discussions in literary form. Among the most

vivid of these recreations is the dialogue that Peterson was teaching, the Symposium.

The scene in this dialogue is a banquet where the guests around the table are challenged

to give speeches in praise of the god Eros, the god of love.

At the end of the sequence of eloquent speakers comes Socrates, who declines to give his own speech but repeats admonishments made to him by a female wisdom figure, Diotima, who urged him toward a highly spiritual form of love that yields fruits of intellectual communion rather than sensual pleasures. This speech is a source of what we today call “Platonic love.”

But we must note that the particular kind of love relations that the speakers mostly have

in mind in their speeches are male same-sex relations, in accordance with Greek

pederastic practices wherein mature men pursued younger men in order to serve as

their mentors while receiving the young men’s sexual favors. Same sex relations are

simply taken for granted among the group.

For example, one of the banquet speakers, the comic playwright Aristophanes, tells a fantastic fable of how human love and sexual desire originated. The people of Earth once existed in the form of balls and rolled around, he says, but they angered the gods, who punished them by splitting them in two. Some of the round creatures that were split had a male and female component, some two male halves, and some two female. So now the split creatures desire reunion with their other half— some desiring the other sex, some desiring the same sex.

At various times in history the Symposium has had a powerful influence on cultural

movements. One of them, typically called the “first homosexual movement,” began in

Germany at the end of the nineteenth century. In publications such as “Sappho and Socrates” (1896), Magnus Hirschfield not only called for the acceptance of same-sex

relationships but argued for the existence of a spectrum of gender identities, coining

such now-familiar terms as “transvestite” and “transsexual.” A cofounder of

Hirschfield’s Institute for Sexual Science, Benedict Friedlaender, cleaved closer than

Hirschfield to the masculist Greek ideal of male love in books such as Platonic Love in

Light of Modern Biology (1909).

These scholars consistently used the respect widely accorded Plato to justify and

enhance their research and advocacy. If homoerotic and bisexual practices have been

around for centuries, they argued, wouldn’t that suggest that those practices are natural

rather than unnatural? If such a venerable ethical genius as Plato could embrace these

practices, how could one possibly consider them depraved?

So when today we are speaking of diversity, equity, and inclusion as regards sexuality and gender identity, a clear historical line can be traced directly back to Plato.

Because philosophy classes are born of the Socratic ideal of seeking truth together, they

can be places where the most hot-button issues can be discussed with a rare degree of

level-headedness, where wildly diverging views can be considered with a patient eye to

their reasonableness and vision.

Any professor can tell you that there are limits to what one can risk. Challenging pervasive prejudices and deep assumptions too abruptly can put students on the defensive and alienate them, blunting their willingness to engage in dialectic. For this reason I, like most professors, have engaged in plenty of self-censorship, and Plato’s Symposium has occasionally been a target of that censorship.

In teaching Plato in introductory courses over a 40-year career, the Symposium has

appeared and disappeared from my syllabus. During the Reagan years I cut it because it

was too shockingly gay. During the multiculturalist wave of the 1990s I brought it back

because it was so fittingly gay. During the Me-Too movement I cut it again because it

was so creepily pederastic.

In none of these tactics did I personally doubt the dialogue’s philosophical or literary value. It was rather that I thought other dialogues might be better received by particular cohorts of students at particular moments in the zeitgeist. My aim was to find the most enticing path into Plato’s most captivating insights.

The current censure of Plato by the MAGA authoritarians in Texas is a mark of a

new era of functional illiteracy among the political guardians of American education, but

it is not entirely without a basis. The sexual culture of ancient Athens has always been

provocative and worthy of controversy. Plato exploited his culture’s erotic proclivities in

order to create a lively philosophical exchange that draws readers into a deeper

reflection on the nature of love and the kind of friendship that can ground enlightened

community.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks, Paul. I can hear the professor’s warm, dialogic voice as I read this very thoughtful piece. For a more monologic soul like me, I think you are probably too kind to the MAGA authoritarians in Texas. But then, I remind myself that you are seeking to build an enlightened rather than outraged community. Bravo. Μπράβο

Thanks, Walter!