Renee Conrad, an environment inspector on a state construction project who lives at Tulalip, can hardly wait to talk with David Buerge, biographer of Chief Seattle and contributor of dozens of articles and posts across five decades to Seattle Weekly, Crosscut, and Post Alley. Ms. Conrad will have her chance Sunday, October 19, at 5 pm at a celebration at Town Commons in the shopping center at leafy, suburban, Lake Forest Park, not a quarter mile from where Lyon Creek empties into Lake Washington.

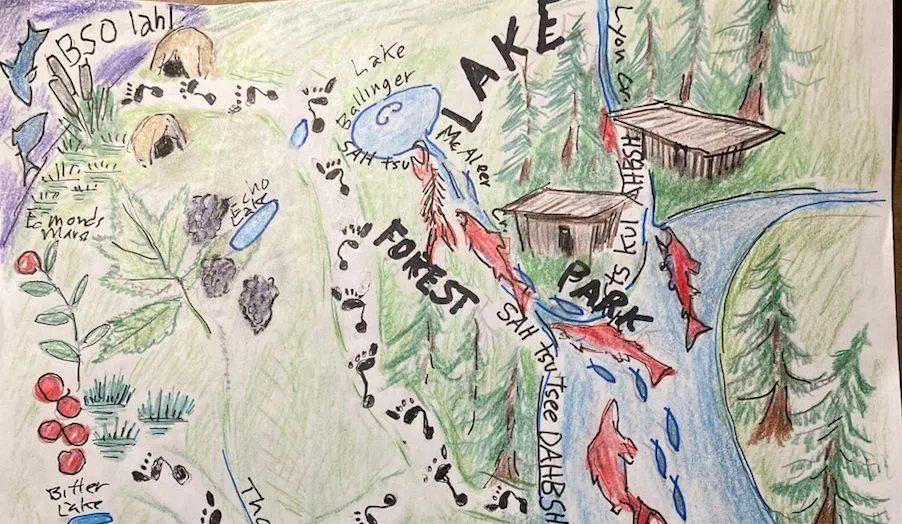

The Indigenous History Day celebration will mark the formal accession of Buerge’s new manuscript, an Indigenous history of Lake Forest Park, into the collection of the Shoreline Historical Museum, a supportive Lake Forest Park neighbor. Buerge will be honored for lifetime achievement by the little group of Lake Forest Park residents who about a year ago raised money to commission his manuscript. Especially on Lyon Creek’s all-but-lost, anadromous salmon run to habitat in Snohomish County.

Conrad herself will have a story to tell about history. She has lived here not all her life, but moved from somewhere else, namely her home and heritage as a Minnesota Chippewa. Living at Tulalip, her day job is an environmental inspector for the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT).

She and a small army of others worked this summer to remove and replace an old culvert under Ballinger Way (State Highway 104). Just a week ago Lyon Creek flowed freely under Ballinger Way, reopening for the first time since at least 1936 (the old culvert’s date) the migratory route for the coho that last week had already been seen poking around the mouth of Lyon Creek by the project biologists.

Full disclosure: Even though retiring from WSDOT nearly 20 years ago, I have not been shy in expressing skepticism about WSDOT’s implementation of its costly court-ordered fish-passage program; but this project shows exactly what every taxpayer dollar, in this case about $7 million, should be delivering — for the fish.

David Buerge’s freshly burnished Lake Forest Park Indigenous history begins its chronology in 15,000 BCE, and he harvests a lifetime of meticulous and passionate discovery into Puget Sound tribes, their histories, and their cultures. Over the years he has vigorously dug into the neglected or even forgotten work of ethnographers, linguists, anthropologists, and others. He has occupied a long-term niche assisting the Duwamish Tribe in historical research supporting its case for federal recognition.

Renee Conrad stands for the huge citizen multitude across our pluralistic demographic and cultural landscape who are keenly and personally focused on the task of fashioning today’s forward-looking correctives from yesterday’s legacies of ecological abuse. When I first met her, as I happened casually to drop by her job site, she was eyeing the installation of the new stream bed. She treated me with a long list of species, much beyond salmon, that the biologists knew to frequent the stream.

It was also serendipity that in a June day I sat at a picnic table near Lake Washington watching David Buerge instruct Lake Forest Park Elementary’s teacher Lisa Collins’s third graders about Lushootseed names and uses for familiar native plants. And about the historic Lyon Creek salmon migration and the disruption of the Creek mouth’s ancient Duwamish communities by new settlers’ 19th century logging, homesteading, and railroading within yards of that picnic table.

The point of departure for the new “land acknowledgment” is the year 1855. It was the years 1854 and 1855 when the leaders of sovereign tribes in their ancient and unconquered realm all across the Pacific Northwest were gathered by Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens on behalf of the United States of America to negotiate under duress the future of their lands. The future of what is now Lake Forest Park was bargained in the Treaty of Point Elliott signed in January, 1855.

There were two sides to the bargain. For the settlers, a gain of the right to settle and own the land. For the Indians a recognition and preservation in perpetuity of their sovereign reserved right to fish, hunt, and gather food and medicine on the lands that had always sustained their ancestors and themselves.

We now find ourselves 175 years into the history, grasping how one-sided was that “bargain” of the 1855 treaty. In Lake Forest Park, it’s not hard to see how advantageously their settlement of the land seems to have worked out for generations of new settlers. On the other side Native Americans were largely displaced, if not to the remote reservations at Muckleshoot, Tulalip, or Suquamish, and then into alien urban market economies. Hovering over the land, never erased and never forsworn by the tribes, was the treaty promises of sovereign tribes’ reserved rights to fish, hunt, and gather.

The Fish Wars of the 1970s led to the federal judge George Boldt Decision. From the Boldt Decision came many years’ state and tribal co-management of Washington’s fisheries resources. “If you put salmon first,” a Nez Perce friend of mine in Idaho says, “everything else will follow.”

In the grand scheme of things, since David Buerge’s starting line at BCE 15,000, 175 years of history is not that long. How do we use an appreciation of 175 years of our past to guide and forge the future in which the land and water is shared and stewarded in the fullest dimension as our most precious Creator-given gift?

Renee Conrad stands for the huge citizen multitude across our pluralistic demographic and cultural landscape who are keenly and personally focused on the task of fashioning today’s forward-looking correctives from yesterday’s legacies of ecological abuse.

Thank you for this well crafted sentence. It sums up decades of efforts to restore salmon and the myriad of positive environmental results that will naturally follow.

Doug- It was such a delight to read your article. I lived in LFP for many years and look forward to reading this history. I currently live in Dunn Gardens. Over the past year and a half we worked with the Duwamish Tribe to develop a native trail in the garden and to learn more about the history of the Tribe on this land. Would love to have you visit the gardens some time and take you on a tour!

Best,

Ruth Kagi

A friend and I attended his speech in LPF Commons this evening. Pardon my echo, but he is a treasure-house of knowledge.

His research on LFP will be available from the Shoreline Historical Museum.

Doug- Thank you for the article. You always have the words and perspective!