November 7, 1931 – September 15, 2025

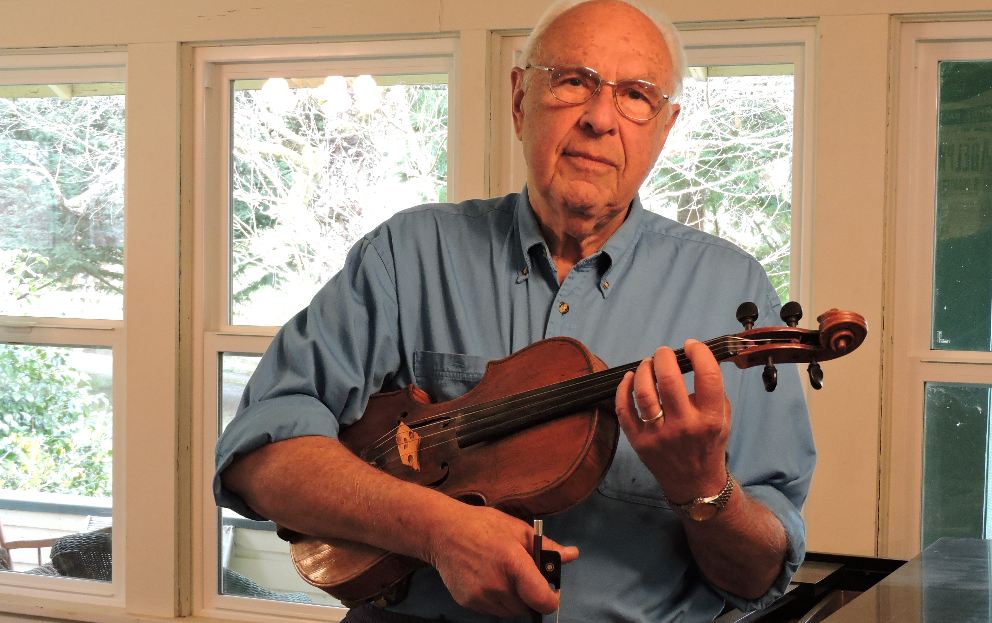

Alan Iglitzin, the acclaimed violist and founding member of the Philadelphia String Quartet, which battled and won a long legal war with the Philadelphia Orchestra to become the University of Washington’s quartet in residence, died on September 15th in his home on Bainbridge Island. He was 93.

Mr. Iglitzin possessed remarkable musical talent and spent most of his career as violist of the Philadelphia String Quartet (PSQ). Following its Carnegie Hall debut in 1964, the PSQ toured extensively throughout the world to resounding praise. A London reviewer called their performances “exceptional in every way,” and Vienna critics noted that the PSQ performed “not with the cold perfection so often characteristic of American ensembles, but the cultured playing of the European kind supported by true musicianship.”

Over time, three of the original members were replaced because of death or retirements, but Mr. Iglitzin always held the position as violist. His daughter, Karen Iglitzin, was the first violinist from 1982-1987.

He also possessed an intrepid entrepreneurial spirit, which prompted him in the mid-1970s to purchase a ramshackle farm on the Olympic Peninsula and turn it into a performance venue for chamber music. Over time, the Olympic Music Festival (OMF) became a summer-long chamber music series that took place in the renovated turn-of-the-century dairy barn. This endeavor consumed most of his life after the PSQ retired circa 1990.

In 2015, Mr. Iglitzin retired as director of the OMF following a stroke that cut short his performing career. His beloved viola, a unique and extraordinary ancient instrument sometimes attributed to Gaspar da Salo and held in great admiration by musicians for its power and depth of tone, has passed on to Richard O’Neill, a former student and current violist of the Takács Quartet.

Due to popular demand by both patrons and musicians, Mr. Iglitzin’s wife, Leigh Hearon, resurrected the festival in 2019. Today, the chamber music series is now known simply as “Concerts in the Barn.”

During the 30 years that Mr. Iglitzin directed and performed at the OMF, he embraced rural life to its fullest. At various times, the farm was home to pigs, goats, cows, horses, chickens, sheep, fourteen donkeys, and, for a brief time, a pair of perpetually screeching peacocks. He loved to chop wood, was an avid gardener, and over the years, transplanted dozens of trilliums onto the farm, which briefly flowered each spring and brought Mr. Iglitzin great joy.

Mr. Iglitzin’s years on a farm were a far cry from his origins. He was born in Harlem Hospital, a few blocks from the drugstore his father, Jacob Iglitzin, a Jewish emigrant from Belarus, owned and operated 365 days a year. A few years after his birth, Mr. Iglitzin’s family moved to the Bronx, where he attended P.S. 70 and received a rich musical education. By the age of seven, Mr. Iglitzin had declared the violin his favorite instrument, and when not playing stickball in the streets, learned to play the violin with a modicum of practicing. Years later, whenever Mr. Iglitzin encountered a former private instructor, he would be reminded of his profligate attitude toward learning the instrument, although he was never criticized for his performances.

Mr. Iglitzin was accepted into the High School of Music and Art and later obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Long Island. He was never tempted to attend a collegiate music conservatory because, he said, students only had one thing on their mind—music. Mr. Iglitzin’s outside activities were prolific, and included boxing, softball, and being his father’s right hand man at the drug store, where he earned the sobriquet of “Little Doc.”

After graduating from college in 1951, Mr. Iglitzin married his high school sweetheart, Lynne Bresler (also a High School of Music and Art graduate). It was then that Mr. Iglitzin switched from violin to viola. The decision was based on sheer necessity—he was getting married, needed a job, and violists were far more in demand than violinists that year. After two short lessons with a fellow violist, he tried out for a position with the Minneapolis Symphony, then conducted by Antal Dorati. He was offered a position and eagerly accepted it, even though he had yet to learn the alto clef. A year later, Mr. Iglitzin was promoted to the position of assistant principal violist.

During his seven years with the orchestra, he discovered the joys of performing chamber music with like-minded musicians. He was a member of the Flor Quartet and String Arts Quartet, both of which performed locally. In Mr. Iglitzin’s words, he soon felt that he was a chamber music artist trapped in orchestral life to earn a living.

During these early years, Mr. Iglitzin also spent his summers at the Aspen Music Festival, where he studied with William Primrose, a preeminent violist of the time. Mr. Primrose described Mr. Iglitzin as one of his “notable” students, and the two men developed a mutual respect for the other. It did not hurt that both Mr. Iglitzin and Mr. Primrose had been amateur boxers in their youth.

In 1960, Mr. Iglitzin joined the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy. Despite his involvement with the orchestra’s union committee (which Mr. Ormandy frowned upon), he was soon promoted to assistant principal viola. And he quickly fell in with three other musicians who were committed to chamber music—Veda Reynolds, on “loan” from the Curtis Institute since World War II whom Ormandy had no intention of giving back, Charles Brennand, cellist, and Irwin Eisenberg, second violin.

Over the next six years, the fledgling PSQ worked unceasingly to make their mark on the world. In 1964, they were invited to perform two series at Carnegie Hall. The first season was an ambitious program including quartet cycles of Bartok, Beethoven, and Schoenberg. The second focused on contemporary music from four countries: Norway, Poland, Hungary and Holland. As Mr. Iglitzin recalls, the reviews from these concerts put the PSQ on the map.

By 1966, the PSQ had decided it was time to shake off the shackles of orchestral life and find a position that supported their aspirations as a string quartet. When Dr. William Bergsma, Dean of Music at the University of Washington, offered the group a full-time residency, the PSQ accepted, but soon learned that leaving the Philadelphia Orchestra was more difficult than they imagined.

A legal war ensued—at the same time the orchestra waged a labor strike that sidelined concerts for weeks—but in the end, the PSQ prevailed (as did the striking musicians). The legal principle that granted the PSQ its freedom was one propagated by Oliver Wendell Holmes—that of sovereign immunity. Mr. Iglitzin never failed to give Mr. Holmes’ concept full credit for releasing the PSQ from the bonds of orchestral life and giving it the opportunity to pursue its goal of bringing chamber music to the widest possible audience. The PSQ learned it had won its suit against the Philadelphia Orchestra on a trip to India sponsored by the. U.S. State Department. Until then, the PSQ had been prohibited from performing in both the states of Washington and Pennsylvania, and with any group other than the Philadelphia Orchestra.

“We went through a difficult mine field to get there, but we did it,” Mr. Iglitzin recalled. “The orchestra found out we don’t play with guns at our heads.”

When the PSQ officially arrived in Seattle, reporters often told Mr. Iglitzin, the de facto spokesperson, “You’re coming to a town which Sir Thomas Beecham (a former Seattle Symphony conductor) has described as ‘a cultural dustbin’. How do you feel about that?” Mr. Iglitzin would respond, “Maybe we can do something about that. We’ll play some good quartet concerts for you.”

In fact, the PSQ’s presence quickly and dramatically changed the nation’s perception of Seattle’s musical stature. Provost Solomon Katz described the PSQ as “the jewel in the crown of the University.” To accommodate overflow audiences, the University of Washington built a new auditorium, Meany Hall. Prior to that, the PSQ was performing double its normal concerts to accommodate ever-expanding audiences. Concerts regularly sold out within a few hours and invariably received rave reviews.

During the 18 years the University of Washington supported its endeavors, the PSQ regularly performed on campuses in Pullman, Ellenburg, Cheney and Seattle.

At the same time, the PSQ was making news around the world during summer tours of South America and Europe. In addition to what is considered standard classical repertoire, the PSQ also performed a great deal of contemporary music. Many composers, including George Rochberg, Paul Chihara, William Bergsma and others, created repertoire specifically for the PSQ.

The PSQ also had a close relationship with composer Alberto Ginastera, who revised his String Quartet No. 2 (originally composed in 1958) with the PSQ’s help and input. The revised version premiered at the Dartmouth Festival in 1968 and is the preferred score today. During one rehearsal, Mr. Iglitzin remembers tentatively asking Mr. Ginastera to clarify the correct pronunciation of his surname. In reply, Mr. Iglitzin recalls, Mr. Ginastera raised his fist and shouted, “JEE-nastera! JEE-nastera! No Castilian! Catalan!”

In 1982, the University of Washington’s funding ceased due to drastic cuts in state revenue. By then, Mr. Iglitzin had purchased a 57-acre farm in Quilcene, WA, intended as a summer retreat for the PSQ to spell them from grueling European tours. In the absence of academic life, renovating the farm became Mr. Iglitzin’s full-time passion.

The farm had formerly been homesteaded by a Japanese-American family, the Iseris, until Executive Order 9066 forced their evacuation in 1942. The Iseris lost the farm after the war and the property moved from one owner to the next. Mr. Iglitzin learned of the farm’s history from locals and said he felt there was a cloud over the farm because of the Iseris’ internment and subsequent loss of property.

In 1984, the OMF opened its barn doors and soon found itself a top local attraction. The rural community of Jefferson County had never encountered chamber music of this caliber before. Festival audiences learned to trust Mr. Iglitzin’s judgment in repertoire and over time, the series grew to summer-long seasons, starting in June and ending in September.

In the mid-1990s, Mr. Iglitzin received a phone call from Sam Iseri, the son of the homesteaders who had originally built the farm and turned it into a dairy/berry business before forced to evacuate. Mr. Iseri told Mr. Iglitzin that previous attempts to visit his childhood home had all been rebuffed. Mr. Iglitzin welcomed him with open arms. Over the years, Mr. Iseri and his extended family became good friends with Mr. Iglitzin. When Mr. Iseri died in 2004, Mr. Iglitzin attended his Buddhist funeral and spoke of his deep friendship with him.

Mr. Iglitzin was known for his dismissive attitude toward most conductors. He made it known that never once had he called one “Maestro,” and would regularly regale guest musicians who performed at the OMF with stories of his encounters with Eugene Ormandy, Otto Klemperer,

Leopold Stowkowski, and other conducting luminaries. His kindest words were for Antal Dorati, whom he respected, and Leonard Bernstein, whom Mr. Iglitzin admired for his accessibility to orchestra musicians. Their first encounter was at the High School of Music and Art, followed by performances at the Tanglewood Music Festival, where Mr. Iglitzin spent his summers before PSQ tours took precedence.

Mr. Iglitzin embraced challenges outside the realm of making music with enthusiasm and a burning desire to know how other people lived. Although he would always say his life was built and revolved around chamber music, he held many other interests—travel, especially to India, which he first visited in the 1950s and regularly returned as both artist and traveler—world history, and Russian literature. He was proud that the PSQ had always concluded Beethoven’s Op. 130 with the Grosse Fugue and not the newer, unremarkable final movement Beethoven’s publisher had demanded, and that boxer Jack Johnson had personally showed him how to put up his dukes when he happened to stop by his father’s drug store one day for a quart of vanilla ice cream.

Mr. Iglitzin is the only two-time recipient of the Washington State Governor’s Award, bestowed first in 1972 and later in 1998.

He is survived by his wife, Leigh Hearon, a son, Dmitri (Eileen), daughters Karen and Lara (Vladimir) and three grandchildren (Ariana Nelson, who is the cellist in the Carpe Diem String Quartet, Anna Iglitzin, and Jacob Iglitzin). Mr. Iglitzin’s sister, Abigail (Iglitzin) Hermann, who was a child piano prodigy, predeceased him.

An audio-visual memoir of Alan Iglitzin’s life from 1931-1966 can be seen on YouTube.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A wonderful piece about such an interesting man and life. Thank you for sharing it. I remember my parents meeting and socializing with Alan back in the late 60s when they were also fairly new to Seattle. It was a heady time for Seattle culture when the PSQ came to town.

What a grand appreciation of this transformative musician and cultural pioneer in our region. I was a young KING TV news reporter who covered the unique story of Alan leading the much-admired Philadelphia String Quartet out of the stuffy city of its birth into the wilds of our Puget Sound country.

I grew up in a Seattle family that deeply valued classical music, though none of us were remotely talented and wouldn’t have dared performing in front of anyone.

My older, all-male TV evening news bosses thought the arrival of Alan, Veda Reynolds, Charles Brennand, and Irwin Eisenberg was not our sort of story. But they let me report it, if only because it involved the lively tussle between the UW and its new musicians “in residence” versus the august Eugene Ormandy and his top tier East Coast/world-renowned symphony orchestra.

Alan’s enthusiastic and humorous personality was just the audience-grabbing front man needed to energize even those who’d never entered a classical performance hall. This musical ensemble would not be the stereotype one expected at that time – men dressed in evening clothes with somber faces fiddling away. Instead, Alan offered us a great show-biz on-camera interview and a new public image of world-class chamber music in our own back yard.

Later I reported on the birth of the Olympic Music Festival, the barn, the bargain “seats” and picnic crowd who listened to performances outside the open doors. All new to the Puget Sound region. Everyone loves a David-and-Goliath story and this was it. The fact those wonderful, talented musicians took the chance to come “Out West” was our good fortune.

I just received my online copy of Strad Magazine where I saw Alan Iglitzin’s obituary. I’m so sorry to hear of Alan’s passing. We shared many musical moments together over the years. A giant in the musical world has passed. He will be sorely missed.

The Philadelphia String Quartet was in residence when I started at the University of Washington as a cello performance major. I was the one of the students, who attended their “open door” rehearsals religiously. From that I became friends with Alan, Charlie and Irv. Veda Reynolds was the first violinist during that time. Later I toured with them as a second cellist. The Philly Quartet played to sold out audiences wherever they performed. The only word I can accurately use to describe their music-making is “sublime.” We in Seattle knew it and so did the countless international audiences, who had the good fortune to hear them when they were on tour.

When I graduated I started playing professionally, became faculty cellist at the University of Puget Sound, married and had children so Alan and I didn’t see each other for a while. I was injured in a car wreck and retrained as a school administrator.

Eventually I became principal of the Quilcene K-12 School District in the town where Alan bought a historic Japanese farm and where he created a renowned music festival. Alan was busy with the Olympic Music Festival and I visited as an audience member and fellow musician. It was so fun to circle back together after so many years of not seeing each other. Life is quite the journey and I’m sure Alan was surprised to hear of me changing careers due to that injury.

A couple years ago Alan called me to join him for lunch with my husband and Seattle Symphony percussionist, Howie Gilbert. We had a chance to get caught up with each other and talk about the old times. He and Howie shared their memories of growing up in New York around the same era. It was a special day that I will cherish forever. He learned then that I was playing my cello again after intensive physical therapy after I retired from school administration.

So now I’m helping lead the Port Townsend Chamber Music Series. It has all come full circle. Everything I learned from years of watching Philly Quartet rehearsals and concerts is still in play. The musical legacy continues and we are all part of it.

Alan’s musical impact cannot be overstated. He was a strong leader in classical music development in the U.S. and world-wide. He was enormously talented and visionary. The Olympic Music Festival was his fullest expression of those talents along with his years in the Philadelphia String Quartet. The positive ripples of his musical leadership will continue now into the future through the many young artists he has touched.

Alan’s extended family and friends have my deepest condolences.