Several times over the past decade I’d be at Suzzallo Library at the University of Washington doing research for a book when a troop of schoolkids came by. The librarian would tell them how they could use the library’s vast collection of microfilm. They could look up a century-old story and take home a digitized image of that story on a memory stick.

I was peering at a screen and scribbling notes on a legal pad. The kids looked at me, as if to say, “Who is this old guy, working with a pencil? Why is he doing it that way?”

I wasn’t looking for one story. I was looking for 25 or 30 stories that morning, to be followed by other stories on other mornings — several hundred other mornings. I was working my way through 10 years of three daily newspapers and several weeklies, writing a paragraph on each story that caught my eye. My aim was to connect the stories into narratives, and organize the narratives into a book. For that, I didn’t want a memory stick; it would be like having a cardboard box of newspaper clippings. I wanted concise notes.

At home, I typed my notes into the computer. Each time I typed them or organized them, I had to think about them. I wasn’t just digging up bits of information. I had to imagine what to do with them. I also had to identify the information I still needed.

I learned this way of research from Lorraine McConaghy, the historian of Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry. In the last year of my newspaper career, she recruited me for a weekend project. My task was to read local newspapers from the 1860s and write summaries of articles about the Civil War. Washington Territory was far from the battlefields, but editors made up for their pacific location by fighting a war of words.

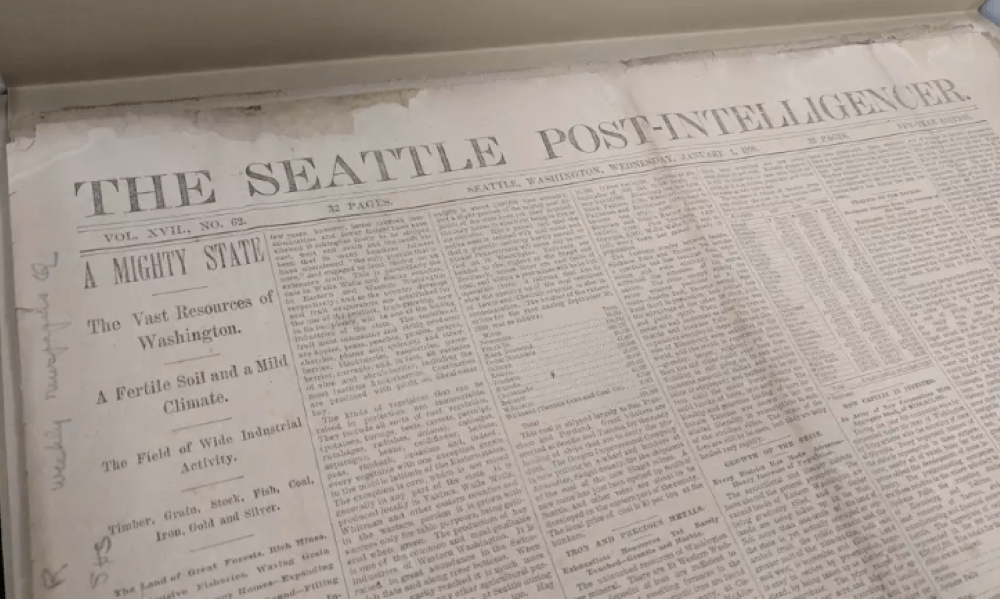

For several hours a day I scanned pioneer newspapers and took notes: name of the paper, date, page, headline, notable facts and saltiest quotes. I was fascinated. I was listening to voices from a world long gone. These were primary sources, unbiased by the knowledge of the future.

I thought, This could be my retirement project. I could write a history.

But a history of what? In my newspaper life, my beats had been business and the economy, and, later, social and political conflict. Well, something of that, but I also wanted a story that had worry, fear, and conflict. Something like the Civil War, but with more of the action here in the Northwest. A depression, then: Washington has felt the brunt of several of those.

I wrote two books. The first, The Panic of 1893 (Caxton, 2018), was about the depression of the 1890s. Most people don’t know about that one, but it hit Washington harder than almost any other state. The second, Seattle in the Great Depression (WSU Press, 2025) is about the depression people do know about, the big one in the 1930s.

Old newspapers were especially good at covering politics, such as the rise of the Populists in the 1890s and the Leftist Commonwealthers in the 1930s. The 1890s papers reported the bank failures — there were lots — but I had to look at reports in the National Archives in Maryland to read why they failed. The 1930s papers did a much better job covering Seattle’s two big savings-and-loan failures. The company presidents were put on public trial, and newspapers covered the courts.

In the 1930s, Seattle’s newspapers wrote about unemployment as a political issue, but not so much as a personal struggle. There were exceptions. The Times had a story of an old man living in a hut in a marsh on Union Bay. The Post-Intelligencer printed the freelance writing of a woman who pretended to be homeless in the dead of winter and spent all night in a movie house to keep warm. The Seattle Star wrote of a family evicted from their South Seattle home, living on the sidewalk.

The reporters who wrote these stories were not activists, seeking to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” Their coverage was matter of fact, sometimes even upbeat: These people are survivors. The papers mostly ignored the most obvious group of unemployed: the thousand men in the “Hooverville” squatter camp on the downtown waterfront. The best primary source on that is the famous UW master’s thesis by Donald Francis Roy, a sociology student.

Old letters can be fine historical sources — if the writer wrote about things of public interest, if the letter was well-written, and (crucially) if it was saved. The correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams is famous for those reasons. But letters between ordinary mortals are mostly about things of interest only to them.

There are exceptions. Researching The Panic of 1893, I found a letter from a woman in Everett who was caring for seven children. In the letter, she pleads with Amaryllis Thompson, a friend in Tacoma, to take her 17-year-old stepdaughter, Marnie, as a housemaid. The writer had wanted to send the girl to teacher’s college, but the Depression had left her with no money to keep the girl fed.

That letter showed the choices people had to make. It was like panning for gold and finding a nugget. But it’s a one-off. It’s in an archive because Amaryllis Thompson was married to a banker, and the archivists of the day saved his papers. The archive has no copy of her reply, so we don’t know what happened to Marnie.

One source for Seattle in the Great Depression was the letters of a philosophy student, Thane Summers, who dropped out of the University of Washington to fight the fascists in Spain. His letters are saved in Special Collections at the UW. Mostly they are introspective; he wrote about what his communist beliefs implied for his own life, including his decision to become a soldier in a European civil war. However, in late 1937, his letters end; in mid-1938, The Seattle Times reports his death.

Another shortcoming: newspapers don’t cover everything. Reporters write what they know and what they are told, so they often miss things that are hidden. You wouldn’t base a history of the attack on Pearl Harbor from newspapers, because crucial parts of the story weren’t reported. Newspaper coverage is often too shallow and wide for stories narrow and deep. But for the history of a city over a period of time — which I was writing about — the daily newspaper is the best “first rough draft.”

One caveat: Reading a decade’s worth of newspapers is not an efficient way to research a book, or to make it pay. You have to like doing it, as I did. For several hours a day I scanned pioneer newspapers and took notes: name of the paper, date, page, headline, notable facts and saltiest quotes. I was fascinated. I was listening to voices from a world long gone. These were primary sources, unbiased by the knowledge of the future.

Poring over microfilm, I often wondered how the authors of the future will do it. Microfilm is an old technology, and a librarian told me it’s difficult to find someone to fix broken machines. Newspapers are also old technology, as are “snail-mail” letters. Of all the stuff we have on the internet — news, opinion, personal accounts, statistics, propaganda, lies — but how much of it will still be there a century from now?

I suppose the researchers of the future will tell their AI to sift through the vast digital midden. Maybe the AI will even write the books — if people still read them.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

That’s funny, when I saw this article, I had been doing just that. I for a year or so, subscribed to archives of the Union-Bulletin, from Walla Walla where I grew up.

I also found archives in the Seattle Times covering my uncle when he worked with then Seattle mayor Wes Uhlman.

Research is incredibly fun and rewarding, but also very time consuming. Like you said, you have to enjoy doing it. To me, it always seems like a bit of a treasure hunt.

By the way, I really enjoyed your new book. You did an excellent job capturing that era of Seattle.