It’s not as if we needed another book about serial killers of the Pacific Northwest. There are dozens already, even a serial killer coloring book for adults: Hi, I’m Ted. Seriously!

Pulitzer-prize winning author Caroline Fraser, who grew up in the Seattle area, has added one more to the serial killer genre; this one with a novel twist.

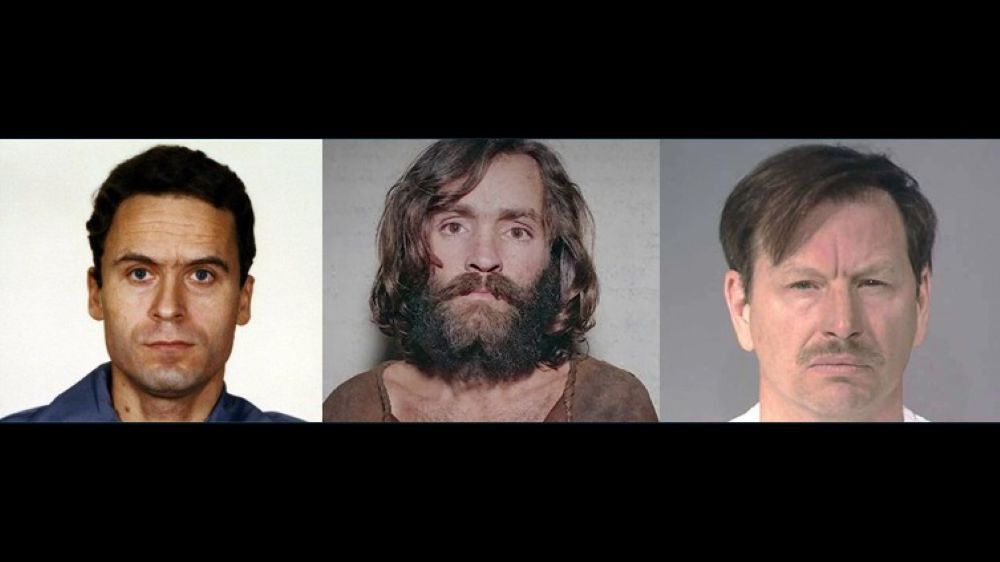

Fraser’s 402-page tome covers not one, but three serial killers with Puget Sound region connections—Ted Bundy (who needs no introduction), Gary Ridgway (the Green River Killer), and Charles Manson (who served five years at McNeil Island before his cult followers went on a murder spree in LA.)

Appropriately titled Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers, Fraser’s book seeks to answer the question we’ve all had for decades: what gives with all the serial killers around here? Is it the depressing winters? Something in the water? Something these demented predators shared in common?

As Fraser posits, there is something in the environment that was common to these serial killers. Specifically, the lead that spewed from the ASARCO copper smelter on the Tacoma waterfront for nearly 100 years, settling on more than 1,000 square miles of soil in the Puget Sound Basin.

Fraser’s premise is that Bundy, Manson, and Ridgway each lived at least part of their lives in this toxic smelter plume and that the accumulated lead in their bodies—in combination with other factors—triggered their mania for serial killing.

Lead has been shown to pose a health risk, even in small amounts and especially in children. Exposure in children is associated with developmental delays and learning problems, antisocial behavior and lower IQs. And studies have linked it to rising crime rates and aggression.

But, as Fraser acknowledges, “recipes for making a serial killer may vary, including such ingredients as poverty, crude forceps delivery, poor diet, physical and sexual abuse, brain damage, and neglect. Many horrors play a role in warming these tortured souls, but what happens if we add a light dusting from the periodic table on top of all that trauma?”

That’s the rub. Fraser works diligently to make the case for lead poisoning (49 pages of end notes). But there is no conclusive evidence that lead poisoning caused Bundy, Ridgway, and Manson to go on their killing sprees.

And if lead is a primary factor in our region’s murder mania, why weren’t there a lot more serial killers terrorizing residents of the Puget Sound region for most of the 20th century, when the smelter was in operation?

As Gideon Lewis-Kraus said in his review in The New Yorker: “Fraser is an outstanding social, cultural, and environmental historian, and she has an effortless way of turning pontoon bridges into villains.” (You’ll have to read the book to understand that one. I still don’t.) “But Fraser’s argumentative style is one of association, a vast crazy wall studded with murders and smelters and industrialists, yoked into patterns with skeins of gripping red yarn. It’s never quite clear whether she thinks she’s really caught the bad guy or created an impressionistic tableau of America’s helter-skelter years.”

Reading and reviewing Murderland prompted me to reflect on my own memories of Bundy. I met him in the summer of 1974 when I was 21 and we were summer interns at the State Department of Emergency Services (DES) in Olympia. It seemed back then like an uneventful summer.

Our small group of interns would go out for lunch most days, including once when I hosted them (yes, including Ted) at my house. We played baseball together. I was reminded of this when I came across a tongue-in-cheek “recap” of a game between the interns at our agency and interns at the state attorney general’s office. It included a roster of our team’s players, including, among others, Bundy, his future wife Carol Boone, and me.

I remember looking out the window of the coffee room at work at his VW Beetle. I thought it was really cool. I recall that some of the time that summer his arm was in a sling or a cast and that he seemed to be out of the office a lot. Neither seemed important. And I remember thinking that Bundy seemed to have it all: good looks, charm, smarts, and on his way to becoming a lawyer.

Though I had no way of knowing it at the time, all of these observations turned out to be related in some way to Bundy’s murderous rampage that—from February to July of 1974—left eight young women dead, seven of them from Washington State.

As one after another of these murders was reported in the papers, public fears of a serial killer on the loose increased dramatically. But it was the July 14 abduction and murder of Janice Anne Ott, 23, and Denise Naslund, 19 that made the public and police fully realize that a serial killer was on the loose.

Ott and Naslund were abducted in broad daylight from Lake Sammamish State Park. There were witnesses, and certain things were noticed by those witnesses. The possible suspect had a VW Beetle. His arm was in a sling. And people overheard him say his name was “Ted.” The sling was key; he used it to appear vulnerable, gain trust, and lure women. For example, he persuaded Janice Ott that because his arm was injured he needed help unloading a sailboat from the top of his Beetle. It was at this point—when Ott and Naslund disappeared—that police began to suspect him. But there was not enough evidence to arrest him. (Their remains were not discovered until September).

Just weeks after the Lake Sammamish disappearances, Bundy sent what can only be describe as a bizarre “resignation” letter to DES, where we worked. Dated August 30, 1974, it began: “It is with some regret, not much, but some regret that I submit this my final resignation. Try to persuade me to stay. Bribe me. Slash my tires…But the world needs me.” The letter closed with an enigmatic warning: “Caution. Tears will ruin the ink.”

One has to wonder if Bundy sensed that it was time to get out of Dodge. A few months later, while a law school student in Utah, Bundy resumed his murder spree. Over a three-week period in late October and early November, he abducted and murdered three young women, all 17.

Fast forward to August of 1975, when news broke that Bundy had been arrested in Utah on a routine traffic violation with evidence including handcuffs, an ice pick, a crowbar, a ski mask, and pantyhose that linked him to multiple disappearances.

I was working a late shift at The Associated Press in downtown Seattle when a news bulletin came across the teletype machine about Bundy’s arrest and that he was a possible suspect in multiple disappearance and murders. It was the first time I realized that the Ted I knew was probably the Ted who had murdered dozens of women, including Ott and Naslund, the summer we worked together. On one level, I was shocked, of course. But on another, subconscious, level, it didn’t surprise me. I can’t explain why, exactly. It was just a gut feeling.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I haven’t read the book yet but it seems like a stretch to me as well. I always felt that the months-long lack of direct sunlight (aka “The Big Dark”), and its effect on serotonin levels, played a likely role in this region producing so many serial killers.

The Pacific Northwest is a very interesting locale. There’s an ‘ energy’ that compels and attract serial killers to this area. I’ve joked to friends that the ‘Space Needle’ is sending signals to folks of this kind.

Behind the gleam of the Emerald City, there is a ‘ pervasive’ eeriness that permeates the air, despite the lushness of the trees, those one-of-a-kind days that only the PNW can have something sinister lurks beneath the surface, that only a certain kind hears the sirens call and answer.

“Fraser’s book seeks to answer the question we’ve all had for decades: what gives with all the serial killers around here?”

Well I guess it’s a question & it had never occurred to me — so I guess I’ll ask it:

— Has western Washington actually produced more serial murderers than other regions? Per capita or by any other reasonable measure? —

Does Fraser‘s book supports the statement “about all the serial killers around here”? Really? Honestly I had no idea. I thought there were monsters all over the place.

I certainly hope her book is fact-based at least with regard to more serial killers “around here”, since if not, then there might not be much point in the book.

—

But by the way I just heard Fraser interviewed on KUOW and she certainly had some strange ideas about what the 60s and 70s were like. She stated that the predominant Zeitgeist of that era was to respect big engineering and business projects… I don’t have the exact words but it was something to the notion that in the 60s and 70s everybody conformed and went along with the establishment.

If you lived through the 60s-70s, I’d say that’s a pretty strange take.