Walking this early July morning from the Pike Market up Stewart and along the blocks to 5th. So many new buildings, so many quiet storefronts, it brought up memories of who used to keep this one-way downtown street alive.

The first Starbucks — it was around the corner from Stewart, in the Market, and it was very conscious that it all should be fun and some collaboration. You could haul your espresso machine in and they would take a look, right there at the counter, for what might be its problem.

No one else had fresh beans, no one else made a cappuccino, in those days, even the word pasta was an affectation. They were as cheery and helpful as a camping goods shop. They were the only Starbucks in the world.

Molbaks was just to the south, a fine gardening shop and they ran it like a very intent hardware store. They had the best clippers and scissors and hose bibs. The Market was not really the place for such a shop but they were so good, you could go there for presents at the holidays and know you would find something.

Stewart Street Cafe — there was a cafe, you entered from First Avenue, a narrow slot of a counter cafe. It was run by a very stout, short man who had been a chef in the Japanese Navy and once you gave your order, he would loudly say “Hi” and get to it. To this day, his was the only place that pan-fried fresh smelt when they were running.

The building was one of the oldest in the market, completely wood-framed. When they tore it down, the largest raccoon I had ever seen, well fed from the cafe, rambled out of the bowels and into the street at Stewart and First and right there, in the center of the intersection, the raccoon was hit and killed by a truck. The pool of blood ran almost to both sides of the street. Police and Fire came and had to rope off the intersection. The raccoon was so big, you could not tell just what it was.

There was a bar on the lower, Pine side of the building, a dark and lonely bar. When it closed, ahead of the demolition, Buster Simpson installed a pole system at each bar stool with a tin cut-out of a patron, finishing a last drink. The cut-out swiveled in the breeze from the broken-out windows.

Across First Avenue, on the south side, the first panini cafe opened, called Botticelli. It was something, and so much something that not an Italian in town did not go there for lunch, or cafe. You could see Angelo in the morning chopping the parsley for the prezzemolo sauce. Somewhere he got fresh arugula and that would go into the grilled sandwiches at the very end. It was as real as the good fellas and no one else was quite doing it quite like that. And no one else had those panini. I still remember the look he gave someone who came in right at lunchtime and tried to order ten sandwiches to go.

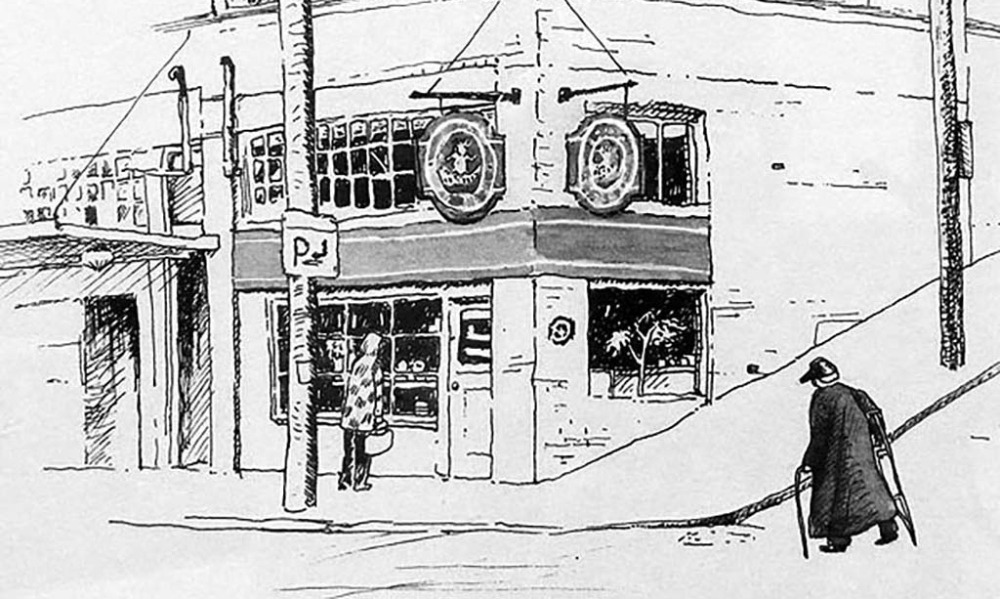

At the very east end of the block, on Second and Stewart, Caffe d’Arte took the corner, opened early and represented the first independent coffee shop in the Market since the legendary Raison d’Etre, on Virginia, had closed. Starbucks had moved south and moved on to tourists only so everyone who worked in the district came to the coffee shop.

Ann Sacks Tile was next door, with the nicest people explaining how your bathroom could have a lovely marble floor. I still have some of the sample tiles; they are busy now as perfect trivets. There was a shudder when rumors started of the building being sold. Clearly the building was coming down and going into the past.

Bergman Luggage held the corner at Third and Stewart. They did not have the hippest luggage in the land, but they had a million accessories, small bags and tags and labels. And they kept a kind of order. Enough that two small shops, one a bar and one a fine dress shop, opened and even seem to thrive next to Bergman’s. The dress shop was very current, the two young women had come from Brooklyn and went each season to the new hip clothing shows in NYC and brought back what was just new.

Seattle had a law that you could not have a bar that you could look into from the street. The Mayflower Hotel opened a block over at 4th and Olive with a very lovely large corner bar, high ceilings. But they had to put drapes on both sides. It seemed a shame. Somehow, over time, the drapes lessened. But you never could look directly at people drinking at the bar.

Bartells was across 5th, on the corner of the Medical Dental Building. Where a drugstore should be. When the flu season started up, we would all go and the pharmacist would line us up for the appropriate shots, kids and grown ups alike.

SeaFirst Bank was in the lot between 5th and 6th, off Stewart. SeaFirst was our shop’s bank, and Joanne was the vice president. We had a fine window washer, Dennis McAuliffe, from Ireland and we needed him. Dennis was a strapping, ruddy-faced, raw-boned big smile Irish fellow — if you ran into him on the soccer field, you bounced off.

Our shop windows on First were 10 feet high and Dennis was the only one who kept them, with great effort, clear and clean, top to bottom. He would come into the shop on Saturdays, to check the scores of the Premier League soccer. Then he would bus over to the University tennis courts and find some young player who wanted to hit tennis balls relentlessly for two hours, backhand after backhand.

One day, he said, “Peter, is it possible you could help?” He showed me his wallet, it was filled with checks, sticking out in every direction, bent corners, probably 30 of them. “I have no account,” said Dennis, “I cannot cash them, but I cannot tell the customers, they will think less of me.” Dennis did the windows at five restaurant and countless shops, he was that good.

So, off we went, to Joanne, at the SeaFirst Bank. We waited and then she had a minute for us. “Dennis has no papers but he has all these checks.” She laughed and said, no problem, I will open him an account, with your name as reference. They cashed all the checks.

Later, a couple of years later, I got a call from the Everett General Hospital. Dennis was there, in terminal care, and he had said we were the closest relatives. We went right over, on the Sunday night. He had his own room, he had advanced throat cancer, and he was fully tubed and bedded. They had given him an iPad to communicate with.

Dennis had come to my son’s soccer games and I left Joe to talk with Dennis. I went out in the hall and asked to speak with the head nurse. She came, we went off to the side and I said, he has no papers. She said, we know that. We have him covered. He died two weeks later. As they said, he got his wings.

That, my friends, that is one America. And that was Stewart Street, for the moment.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you, Peter. It all comes back.

Great article Peter. A bygone era for sure. As an ardent growth proponent I now look back with angst to what we have become. The irony of the country’s march towards authoritarianism contrasted with Seattle’s leftward tilt for-bodes the bad times ahead for both.

Seattle is sick, you can easily see this. I don’t see authoritarianism anywhere in this country.

Avoid mainstream media like the plague of lies and misinformation it is. It’s run by those with a stake in dismantling our cities and country. Eyes open!

And that’s the way it was; nostalgia at its best.

And there was the guy, a single parent of a little girl who managed the parking lot at 1 st and Stewart who created a spot of joy. We often talked about what little girls need. When he past patrons and staff installed a plaque on the side of the plywood booth in his honor. He was what community life is about. I am in his debit

THANK YOU for this beautiful reverie… so grateful to have been here in Seattle for all these years!

After 25+ years in the Terminal Sales Building, thanks for such wonderful memories…

Ah yes! How I miss those days SO much. Thank you for this delightful article to start my day.

Thank you Peter, for reminding me why I fell in love with this small town I came to 55 years ago.

This was fantastic, thank you! But the raccoon…😪

Those were wonderful times Peter. Thank you for bringing the memory and the community to live with us again today. The people, the memories and those times are not completely gone…they live with us in this day through your marvelous recollection and in our days ahead. Thank you.

OMG, does it all come back, even to my leaky cranium: Angelo eyeing the beauties across the counter at Botticelli, Buster Simpson turning dumpster detritus into street decor, pedestrian-watching from the relative privacy of Oliver’s Lounge at the Mayflower, sipping coffee with fellow poseurs at Raison d’Etre (my husband and I called it Raisinet), that fat urban racoon moving out on very short notice, and strangest of all, friendly bankers! It was life on another planet. Thanks for the return trip.

As a 75 year-old native, this was a nice stroll down memory lane. I recall the market at third and Stewart – the Security Market? – and the Blue Diamond butcher shop inside. Many years later I noticed the stenciled pigs on the coolers at the Leschi Mart. I asked the owner at the LM and he confirmed he’d bought them from the Blue Diamond when it closed.

I also remember shopping for clothing samples at the Terminal Sales bldg and many years later, my psychiatrist relocating from Bellevue to the TSB.

Seattle used to be very good at creating these urban neighborhoods, and I remember being at the epicenter of First and Virginia. The Weekly was upstairs in the handsome Terminal Sales Building, Patrice’s Virginia Inn was just across the street, where Bill Gerberding would sit in the window and beckon me to join him, and Peter Miller Books was a place to drop in and meet architects and laught at Peter. I remember Gerry Schwarz lived on the corner and he and I helped baptize the Moore Theatre for a Pergolesi comic opera. Who lost that recipe book?

Proustian! My late friend the cartoonist turned Japan restaurateur Mike Dougan was one of the first 8 Starbucks baristas. He told me every barista was 100% idealistic about great coffee and stoned all day every day. And the coffee was 1000% better.