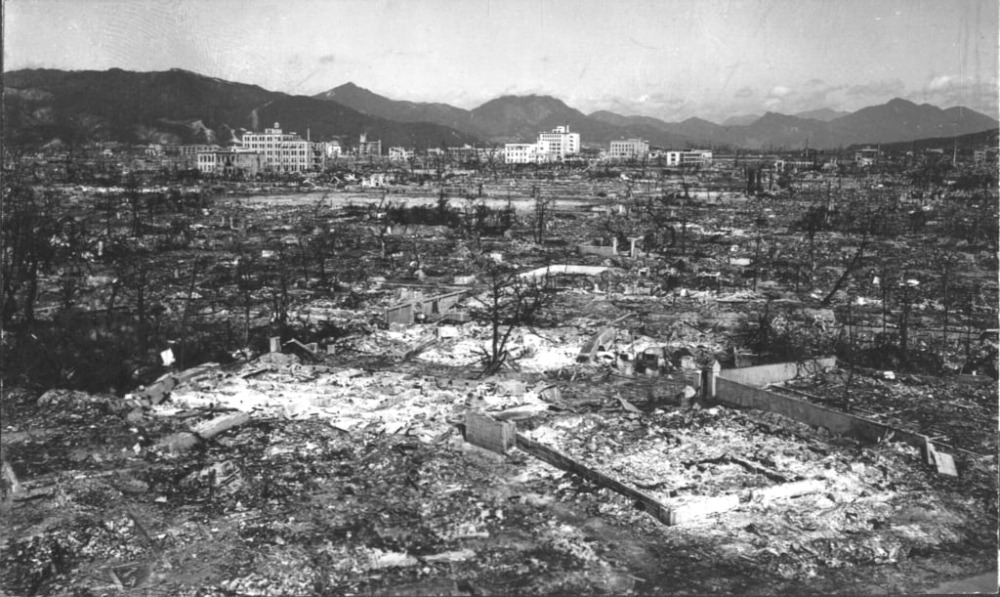

A jaunty young Navy lieutenant from Oregon, Mark Hatfield, was one of the first Americans to see Hiroshima in 1945 after a U.S.-dropped atomic bomb wiped out much of the Japanese city and killed 140,000 people. A second bomb, using plutonium manufactured at Hanford, was dropped on Nagasaki three days later.

During the late 1980s, at a breakfast in DC’s Hay Adams Hotel, I and three colleagues were held spellbound as U.S. Sen. Mark O. Hatfield, R-Oregon, spoke of the galvanizing episode of his life. Hatfield was committed to the abolition of nuclear weapons, even as the Reagan Administration was expanding the U.S. arsenal.

An 80-year anniversary has arrived this weekend, in time for two passing pilgrimages. A Hiroshima survivor, 83-year-old Noritmitsu Tosu and his son Fumi, will lead a Fierce Nonviolent Pilgrimage to Hanford and other Northwest nuclear sites. The first plutonium-producing reactor has become a national historical park.

Four Roman Catholic prelates, including Seattle Archbishop Paul Etienne and two cardinals appointed by Pope Francis, are headed in the opposite direction. They will visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki on a Pilgrimage of Peace. Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago is a former Bishop of Spokane, his diocese including uranium mines on the itinerary of the Norimitsu delegation.

Norimitsu Tosu lost a brother and sister to the Bomb, and the three-year-old came within two minutes of dying in the blast. He had just finished a walk outside with his mother, 1.7 kilometers from ground zero. He remembers a flash and his mother pulling him out of the rubble. “She was bleeding all over: She cried, ‘Help us, Help us,’ but of course no one helped us because everyone was in the same situation,” he told the National Catholic Reporter years later.

Other memories were of the smell, bodies of dead people and horses, and “lots of very very poor kids without food.” As well, “People were dying five to seven years after the Bomb, leukemia mostly.”

His son, Fumi, recalled in an interview, his father’s longstanding silence about the experience. “My sense was he couldn’t talk about it, he was running from it,” said Fumi. “He handled 60 years without talking about it.”

The elder has since become a passionate foe of nuclear weapons, telling the Catholic pubication, “We are used to relativism. But there is an absolute evil. And if I pick out one thing that is absolute evil, it is dropping the A-bomb and there is no excuse for that.”

He has gone on to an achieving life, coming to the United States, matriculating at Brown and Yale, teaching at the University of Tokyo and returning to teach at Yale. He converted to Christianity. He remembers Hiroshima, before 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, as “a very beautiful place” with many temples and a girls’ high school next door.

Son Fumi is based in Portland, active in the Catholic Worker movement, whose founder Dorothy Day was praised by Pope Francis in his speech to Congress, and has become a coalition builder. The tour of nuclear sites is sponsored by such groups as Columbia Riverkeepers, and will interface with the Yakama and Spokane Indian nations. He praises President Obama for a penitential trip to Japan, but notes: “President Obama went to Hiroshima but he did not apologize.”

Early in World War II, President Roosevelt voiced hope that combatants would spare civilians. The Luftwaffe’s blitz of British cities ended that hope. In time, to use Churchill’s words, “He who sows the wind shall reap the whirlwind.”

Such a whirlwind it was. The July 24-25, 1943, bombing of Hamburg triggered a firestorm, killed 37,000 people, injured 180,000 and destroyed 60 percent of the city’s homes. The February 13-15, 1945 bombing of a largely undefeated, refugee-crowded Dresden killed upwards of 25,000: Queen Elizabeth II would make her own penitential visit to the German city.

Spurred by memories of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. was not of a mind to show mercy toward Japan. The March 9-10, 1945 bombing of Tokyo by Boeing-built B-29s destroyed 16-square miles of city, rendered 1 million people homeless and killed an estimated 100,000. (Of the 140,000 dead of Hiroshima, only 10,000 were soldiers.)

Yet, Japan refused to surrender and America feared the casualties of an invasion. The decision to use the Bomb was made by Harry Truman, who didn’t even know about the bomb when he ascended to the presidency at the April 12 death of FDR.

Only the U.S. had resources to build the Bomb. A cross-country nuclear culture sprouted during Cold War years after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. Oak Ridge produced uranium for “Little Boy,” the Hiroshima bomb. Hanford made plutonium and accumulated the nation’s largest concentration of high-level nuclear waste. Other bomb production sites were Amarillo, Texas; Savannah; South Carolina; and just outside Denver.

In our Tri-Cities, you can shop at Atomic Foods in Pasco. A Richland boulevard is named for Gen. Leslie Groves, overseer of the Manhattan Project. The Columbia High School athletic teams are the Bombers, with the moniker of a mushroom cloud. On a 1979 investigation project, Seattle Post-Intelligencer scribe Eric Nalder would ask a bevy of Hanford brass if the Bombers’ baseball team had ever played a Japanese squad. They were not amused.

The dual purpose Hanford N reactor, dedicated by President Kennedy in 1963, produced plutonium for a quarter century. But, like Chernobyl, it was built around a graphite core and had no containment dome. A commission of scientists, the Roddis panel, named to evaluate reactor operations, came away appalled. They disagreed only on a timetable for shutdown.

The Cold War produced signs of sanity. Following the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. agreed to a ban on nuclear testing, a treaty ratified by an 81-19 vote in the U.S. Senate. But there remained the prospect of accident, miscalculation and/or madness. There has been proliferation. The.world now has a Muslim bomb (Pakistan), a Hindu bomb (India), a Jewish bomb (Israel) and an Orthodox bomb (Russia).

As pointed out by Fumi, there is the Pakistan-India conflict of two nuclear powers and “we have a narcissistic, unstable man in the White House.” The campus-like Bangor Trident submarine base on Hood Canal is perhaps the country’s largest nuclear weapons arsenal.

The secular pilgrimage will also address major industries, such as Boeing and Lockheed-Martin, which have manufactured tools of the nuclear age. “I don’t fault anyone,” added Fumi, “but I would like to see them use their talents for peace rather than war. That way, we better ourselves.”

The father-son team, and supporting cast of young people, is in Eastern Washington, hearing from communities impacted by nuclear weapons at Hanford and Spokane. They move west on Sunday (8/3) for an 7:30 evening “reflection” at the University United Church of Christ, at 4515 16th NE in Seatttle. The pilgrimage will make a Bainbridge-to-Squamish United Church of Christ (9 miles) “Peace Walk” on Monday, convening at 11:30 am at Waypoint Park.

The pilgrimage hoofs it again Tuesday, from Squamish UCC to Ground Zero-Bangor, convening 8:30 am at the church, concluding with a 6 pm potluck and program at the protest site. On Wednesday, the 80th anniversary, it’s back on the mainland, gathering in front of Lake Forest Park city hall and going all the way to Green Lake for a 6 pm observance.

Sen. Hatfield never got over Hiroshima, but influenced events. The Reagan Administration was set to shut down N reactor, but faced furious blowback from Hanford boosters. Hatfield forced the issue, approaching me at a Salute to Congress dinner and leaking news of the shutdown.

Hanford’s days producing plutonium were about to end. I submitted the story with five minutes to deadline, my most satisfying scoop in a half-century of journalism.

This article also appears in Cascadia Advocate.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

” . . . Muslim bomb (Pakistan), a Hindu bomb (India), a Jewish bomb (Israel) and an Orthodox bomb (Russia).”

“We’ll try to stay

serene and calm;

when Alabama

gets the bomb.”

R.I.P. Tom Lehrer

“Columbia High School” -huh? Was there a merger among Richland, Kennewick, and/or Pasco high schools?

Thanks for an extraordinary story, Mr. Connelly. This is the best essay I’ve read on the commemoration. The Hatfield details, along with the two pilgrimages, are rich. And kudos on your scoop!