In a remarkable upset, progressive State Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani defeated former Governor Andrew Cuomo in New York City’s Democratic mayoral primary.

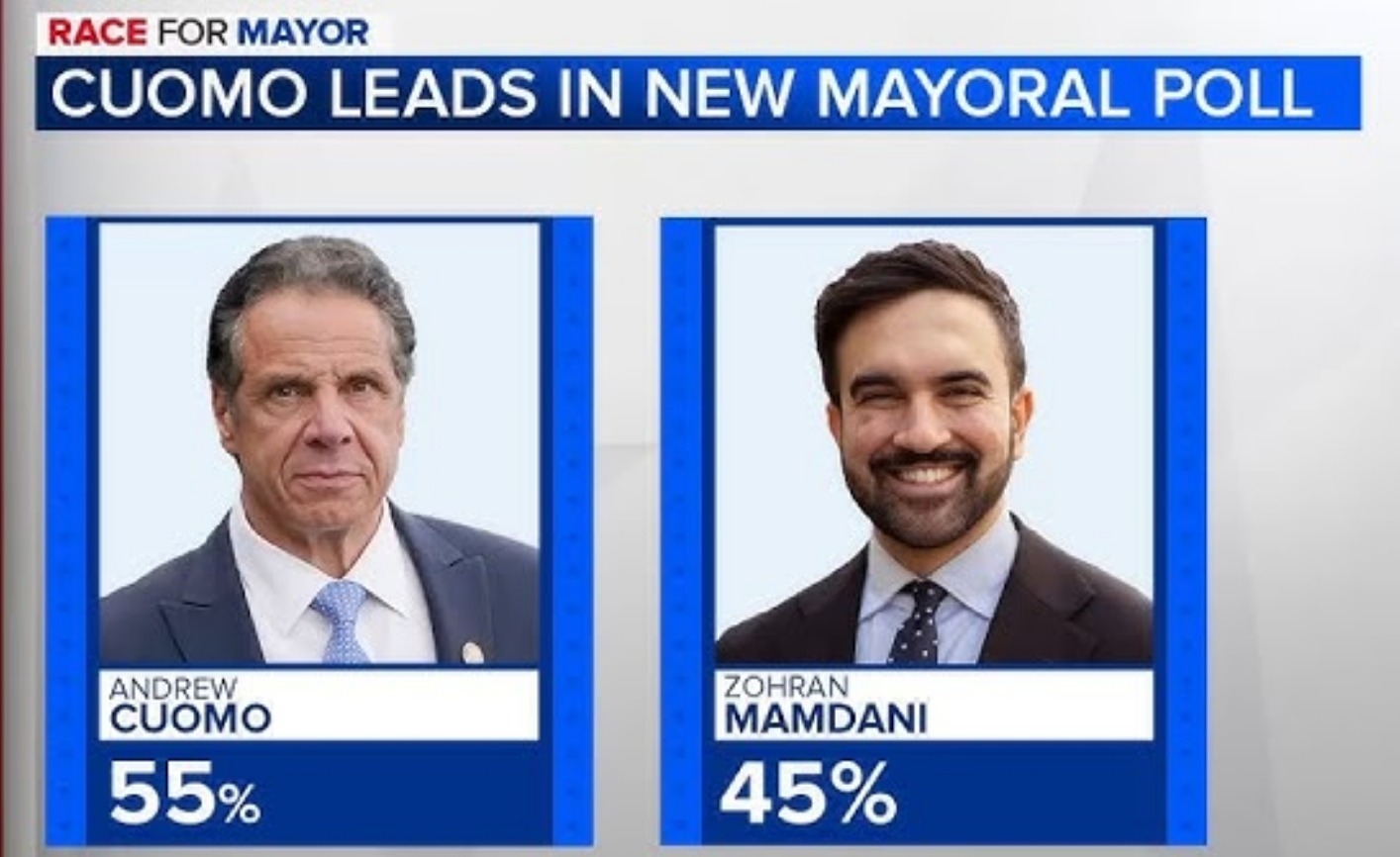

Early polls showed Mamdani starting his campaign with around 1% support. Just six weeks before the June 24 election, his support was only at 11%, while Cuomo led with 49%. Three separate polls, conducted by Yale/YouGov, Marist College, and the Manhattan Institute within two weeks of the election, still showed Cuomo ahead by 12 points or more.

Mamdani won the primary as the clear leader with 56% of the votes, totaling 545,334 votes. His campaign claimed that this was “the most votes any Democratic primary candidate has received in 36 years.” Cuomo received 44%, or 428,530 votes.

Although NYC is the largest city in the U.S., this election was not on a national stage. Jared Leopold, a Democratic strategist, summarized it well: “Communicating in a Democratic primary in New York City is very different from communicating in a swing district in Iowa.” For example, the white population makes up 31% in NYC, but 58% nationwide.

Nevertheless, a quick look at his initial support and his victory sharply contrasts with Vice President Kamala Harris’s initial support and loss. In roughly the same amount of time before Election Day for both Harris and Mamdani, Harris was 2% behind Donald Trump according to a New York Times/Siena College poll, and Mamdani was 38% behind Cuomo. Mamdani won despite performing poorly with low-income voters, losing the majority of Black voters and criticizing Israel while showing sympathy for the Gaza Palestinians. All three conditions should have led to a Democratic candidate losing.

How was Mamdani able to quickly build a populist supporter base to defeat a two-term former Governor in less than two months? Perhaps most surprisingly, he declared himself a Democratic Socialist, a label criticized daily by the MAGA media and rejected by mainstream Democrats.

Mamdani’s election victory revives calls within the Democratic Party for it to be more explicit in promoting government policies that provide social benefits, which attract younger voters. Other Democrats worry that his win will only lead candidates to reject moderation, potentially alienating more conservative older voters. Whatever strategy candidates choose, there are five lessons that the Democratic Party can learn from the Mamdani campaign.

First: Don’t assume an economic argument resonates with all low-income voters.

In his election night victory speech, Mamdani said, “I will fight for a city that works for you, that is affordable for you.” New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez congratulated him for his “dedication to an affordable … New York City, where working families can have a shot.”

Mamdani presented his election message as making New York affordable for residents. A reasonable assumption would be that a large majority of low-income households—those 32% of residents earning less than $50,000—would vote for Mamdani based on their economic needs. Surveys showed that 25% of them cannot afford essentials like housing, food, and healthcare.

All the media celebrating Mamdani’s victory overlooked a puzzling fact. Based on available data, Cuomo secured 49% of low-income voters, while Mamdani only managed 14%. An example of praising rather than critiquing Mamdani’s win is Politico’s respectable article “5 takeaways behind Mamdani’s historic NYC win.” The closest it gets to acknowledging this discrepancy is casually mentioning that “Cuomo outperformed him with voters in the lowest income brackets.”

Ignoring this significant gap overlooks how it happened. It is essential to survey low-income Cuomo voters to understand why they didn’t vote for Mamdani, despite his campaign promising to improve their financial lives. Mamdani’s support was notably higher among the low-income Asian community than in the Black community, where Mamdani, in a poll taken just before the election, received only 8 percent support compared to Cuomo’s 50 percent. It’s possible that offering economic solutions without considering a community’s culture has its limits.

Second: Understand a community’s media culture and then communicate your message through it.

This isn’t about identity politics based on ethnicity, age, or gender; it’s about understanding the cultural context of each targeted community. Identify what medium or activities it uses.

For example, Mamdani reached out to youths from different ethnic backgrounds through online videos, which younger citizens often watch. In these videos, he spoke Bangla to connect with South Asian youths living in rentals who felt the Democratic Party ignored their increasing rents. He acknowledged their urgent need, called it a housing “affordability crisis,” and pushed for freezing rents for approximately 2.4 million rent-stabilized tenants.

Mamdani reached a dormant voter base available to the Democrats but not motivated to vote for them. A Cornell University research center found that tenants are an underutilized voting bloc capable of swinging elections to the left, but only when candidates campaign on expanding tenant protections, such as the ones Mamdani campaigned on.

As a result, Mamdani’s campaign mobilized tenants to help him secure 45 percent of the first-round popular vote in the Assembly districts dominated by rental units, while Cuomo received only 33 percent. Significantly, in areas where Mamdani won a majority of the vote, turnout increased by an average of 20 percent compared to the last Democratic mayoral election. Meanwhile, Cuomo’s percentage remained consistent with previous elections.

A surprising positive result was that more men supported Mamdani than Cuomo, as surveys showed that men, not women, were more worried about housing costs. This is good news for Democrats, who often struggle to get the majority of male votes. For instance, in 2024, men preferred Trump by 12 percentage points, with 55% voting for him versus 43% for Harris.

Third: A key personal endorsement outweighs institutional endorsements.

The Cuomo and Mamdani race magnified the limitations of institutional and political endorsements.

Unions are the largest and often the most crucial institutional support for Democrats in city elections. Cuomo received endorsements from the largest and most influential unions, such as the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council and Local 32BJ SEIU. However, Speaker of the New York City Council Adrienne Adams received the endorsement of District Council 37 (DC 37), the largest public employee union in NYC, along with other major unions. Nonetheless, Adams finished fourth with less than 5% of the votes. There was no polling indicating which of the primary candidates union members supported the most.

The other major institutional support for any politician usually comes from their party and its leaders. Cuomo had endorsements from the Manhattan Democratic chairman, the leader of the Brooklyn Democratic Party, and the Chairman of the Democratic Organization of Queens County. Despite the party leadership representing the three largest voting boroughs, Mamdani won all easily.

Cuomo also received endorsements from 42 current and former elected officials, but one endorsement carried more weight than all the others—Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s. Her influence on elections was clear in the previous mayoral race when progressive Maya Wiley saw her polling double, allowing her to finish second after receiving AOC’s endorsement. Less than three weeks before Election Night, AOC finally decided to endorse Mamdani, even though Cuomo still had a comfortable lead. It was a major boost for him and sparked city-wide excitement about Mamdani’s campaign.

In her endorsement speech, she gave some practical advice. “Even if the entire left coalesced around any one candidate, an ideological coalition is still insufficient for us to win. We have to have a true working-class coalition.”

Mamdani did not win over most of Cuomo’s core Black and Brown voters over 45. However, AOC’s support made a difference since Cuomo’s numbers remained relatively steady from his base in the last election. Meanwhile, Mamdani’s voter turnout among those under 45 surged across the city. The endorsement of a vibrant, young, populist leader motivated younger voters to go out and vote. Mamdani needed AOC’s support as an anti-establishment figure, something the unions or the Democratic Party could not provide.

Fourth: Pay more attention to deploying your campaign money than measuring its size.

Both candidates raised about $8 million in total campaign funds. Half of Mamdani’s funds came from public funds matching his smaller individual contributions; he averaged $87 from 20,700 donors, while Cuomo averaged $700 from 5,733 donors.

Independent third-party PACs donated to each candidate, but Cuomo’s received $25 million of their expenditures supporting him, while Mamdani’s received a total of $1.7 million from them. The difference in the amount of money backing each candidate reflects the wealth of the vested interests involved.

It is a common misconception that money buys elections. Often, that is true, but not always. If the public wants to see a fair, open discussion on policy issues, they usually support using public matching funds to facilitate that discussion and counteract the influence of money, which can restrict the arguments that are presented to the public.

A large campaign fund does not guarantee its efficient use. Comparing NYC’s Campaign Finance Summary of the 2025 Citywide Elections reveals a stark contrast in how the campaigns spent their funds. Mamdani’s reports run to 37 pages of line-item expenditures. Two things stand out: the repeated funding of campaign events and the large number of paid staff organizers. Cuomo’s reports required only 14 pages with far fewer paid organizers and events.

Mamdani stated in a TV interview that his campaign had 40,000 people canvassing. That is hard to believe, but with over 20,000 individual contributions from within the city, it could be true. Looking at his expenses, it seems that his large grassroots effort was managed by many organizers, most likely part-time staff members.

This pattern is evident in the final two months before the election, when Mamdani caught up with and overtook Cuomo in support. During that time, Cuomo spent a quarter of a million dollars on consulting fees, while Mamdani spent none. The last record of consulting fees from Mamdani’s campaign before Election Day was in March, with $10,000 allocated for research.

A lesson for Democrats is to go beyond simply discussing building a grassroots organization by investing funds to hire organizers and providing them with research-based plans to develop an effective grassroots campaign effort.

Fifth: The candidate’s personality overshadows an opponent’s character flaws.

A candidate’s campaign that solely attacks an opponent’s flaws is not enough to motivate voters to support them, even if it casts the candidate in a more positive light. This was a challenge for Mamdani in overcoming Cuomo’s support.

Michael Lange, writing How Zohran Mamdani Can Win on Substack, provided a good background on how Mamdani and others relentlessly attacked Cuomo for months. Despite this, nothing seemed to affect his standing in the polls. People did not mind that the State Attorney General had found twelve “credible” sexual harassment allegations against him, nor were they upset that nursing home deaths during COVID-19 were undercounted by thousands.

Lange correctly predicted that Mamdani’s victory relied on securing the votes of college-educated, under-45 (Millennial & Gen-Z) participation in the Democratic Primary. Lange could have also included renters in this analysis. However, he wasn’t the only one viewing this path as Mamdani’s best option. The conservative Manhattan Institute poll found that a significant source of support came from 18–34-year-old college graduates, with 67% ranking Mamdani first compared to just 6% for Cuomo.

Educated youth have historically been a progressive part of the electorate. But they needed something more than just progressive ideas to motivate them. Progressive Senator Bernie Sanders failed to energize them when he lost to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 New York Democratic Primary by 16 points.

When candidates inspire voters, they will vote. Inspiration can’t be packaged, but it grows when voters feel a candidate listens to them, meets their needs, and identifies with them. Presenting a good candidate as an option over a bad one isn’t enough.

A key ingredient for victory in any election is a personality that connects with voters. While that alone isn’t enough to win, it may be essential.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Another good piece — thank you, Nick. Applying your logic to Seattle’s mayor’s race, I think we can agree that Katie Wilson is generally following your model:

1) Like ZM, she is highlighting affordability, but also identity (because politics today, and maybe always, is/has been about identity). Her campaign highlights her role as a young renter.

2) Like ZM, she is busy on social media (especially instagram). She doesn’t have Mamdani’s remarkable sense of humor — but few do.

3) Like ZM, she hasn’t gotten the big endorsements; even US Rep. Jayapal endorsed Harrell. But she has won the sole backing of every Democratic legislative district org in the city, and some key individuals.

4) Like ZM, she is raising less than the establishment candidate (but not by much, at least judging by the two campaigns, but not including the pro-Bruce PAC; amazingly, Wilson has raised $449,000, relying heavily on democracy vouchers). She has far more individual contributors than Harrell. And she has a small army of volunteers.

5) Few can match ZM’s upbeat, affable style. Katie Wilson is a brainiac, but she’s also charming.

https://youtu.be/DDNxGxTZujc?si=pR99yt4fRYsgN_Xt

Here is Katie, using Common Power, to introduce herself to Seattle voters

https://youtu.be/DDNxGxTZujc?si=pR99yt4fRYsgN_Xt