During my Garfield High School days I often listened to historical vignettes on Seattle radio station King AM. Those mini-stories, floating from my parents’ living room floor console, were filtered through the nasal twang of Pacific Northwesterner Nard Jones.

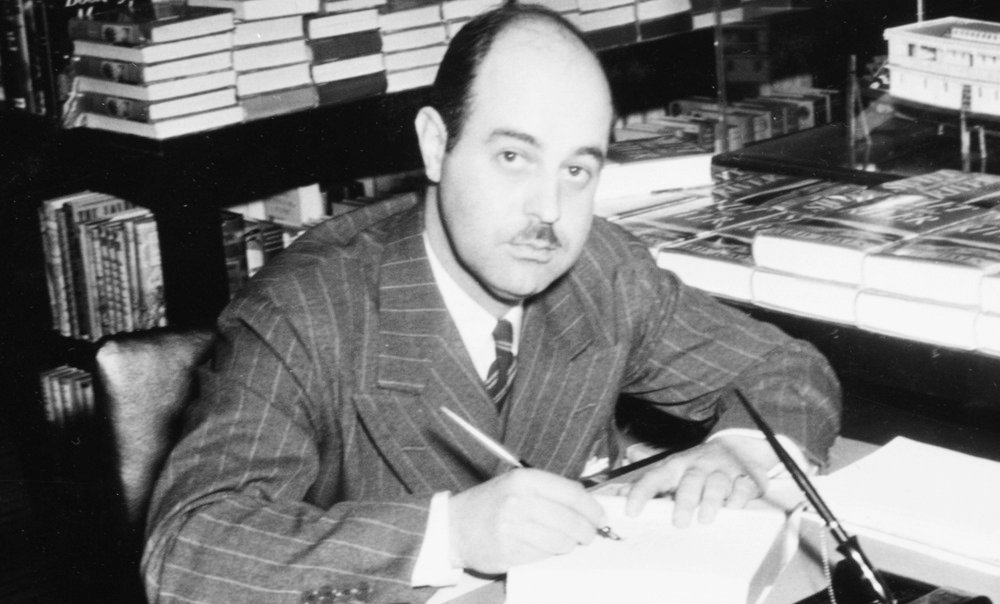

Nard was rooted in Pacific Northwest soil. Raised in the tiny town of Weston, Oregon, he graduated from Whitman College in Walla Walla, then migrated to Seattle where his journalistic career took him to the position of chief editorial writer for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

His love of regional history was an integral part of his stories, basic news, and interview subjects. In spite of his journalistic duties Nard Jones wrote 17 books, most with Pacific Northwest themes; over 300 stories; and a mountain of radio programs. He had one national bestseller, Swift Flows the River, and several notable regional sellers, including a history of Washington State called Evergreen Land and The Great Command (a history of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman).

In 1990, Nard’s first novel, Oregon Detour, was republished. Allegedly based on several characters from his hometown of Weston, Oregon — the fictional town in Oregon Detour was called “Creston” — the book caused something of a scandal in Oregon. Oregon Detour, originally published in 1930, was at first greeted with mirth and good humor in Weston. Soon, however, the local Methodist Church and the Saturday Afternoon Club, both dominated by prominent women, found Detour’s realism and discussions of sexuality unacceptable.

Nard’s new book disappeared from the shelves of both the Weston public and high school libraries. As late as the early 1980s Weston readers curious about their hometown writer had to order Oregon Detour through the Umatilla County Library in Pendleton, Oregon.

Criticism and false rumors about Nard’s novel reached such a crescendo that the author finally submitted several disclaimers to the publisher of Weston’s local paper, the Weston Leader. In one such letter Jones complained that he “would not intentionally speak in a derogatory manner about those for whom he has the highest regard.” Next he stated a hope that “the great majority of my hometown people will read the book purely as a story.” Alas, his hopes would be dashed. Oregon Detour, in the realistic tradition of Sherwood Anderson and Sinclair Lewis, became in effect a banned book.

In his 1972 posthumous book Seattle, Nard Jones salutes the growing body of literature and writers emerging from the Seattle area. The only author’s name he left out was his own, Nard Jones — novelist, historian, newspaper man, 1904-1972.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nard Jones 1972 book “Seattle” revealed a man who reveled in his misogyny. He attacked women’s right to reproductive choice, recently approved by Washington’s voters, and then wrote “It would not surprise old-timers if the issue arose again with an opposite result.” Obviously Jones’ opinions were and remain out of step with those who lived then and live today in his adopted city and state.

Jones then referred to a fellow well-known PI journalist of his day as “Hilda Bryant, the woman reporter” – a sex modifier he attached to her that was irrelevant to the issue he had raised that was connected to her reporting.

When Jones discussed two long-serving women elected to the Seattle city council, with many and diverse accomplishments, he identified them only as the wives of their two husbands – both men’s names he misspelled. He then stated “Somehow these trailblazers also could only think of little more than improving our parks…” Those women were top vote-getters in their races.

Jones’ publisher Doubleday subtitled this unfortunate book as “A fresh look at one of America’s most exciting cities.” Even when it first appeared in bookstores, “Seattle,” by Nard Jones, exuded a stale, unpleasant odor from the mind of a man whose views were well past their pull date.

Thanks for setting the record straight on Nard, Barbara —or Bobby as those of us privileged to know you called you. Nard was typical of so many misogynists in the press then and, I fear, even now.