Say this for Donald Trump: he’s done wonders to revive interest in President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s accidental successor, survivor of an impeachment attempt, and strong contestant for the nation’s worst president. Need a brief primer on the man? He settled in Tennessee and eventually had as many as ten slaves. A negrophobe but also an ardent Unionist. Still, he felt he was condescended to by the men in the Slave Power, for he was just a landowner in a small way and was not invited into The Club, a slight that rankled. When war broke out, he was Senator of Tennessee, and the only senator from a seceding state to remain a fierce defender of, and loyal to, the Union. Because of this, he came to Lincoln’s attention and was tapped to be military governor of Tennessee mid-war.

Subsequently, Lincoln, who like Joe Biden valued Unity, felt a former slave-owning Democrat from a southern state would send a strong signal, so he dumped poor Hannibal Hamlin of Maine and took Johnson on as his running-mate. At the time, Lincoln’s chances to get re-elected in 1864 looked very poor. Because Lincoln was a Republican and Johnson a Democrat, they formed a new party, called the National Union Party. (You can thereby reject the Republican party’s cherished epithet, “The Party of Lincoln.”)

The insecure Johnson was apparently drunk as a skunk before Lincoln’s inauguration, when he gave a rambling, incoherent speech in the senate chamber immediately forgotten after everyone marched outside for Lincoln’s soaring Second Inaugural Address. Later Lincoln, in characteristic generosity, forgave him, saying, “I have known Andy Johnson for many years; he made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared; Andy ain’t a drunkard.”

Andrew Johnson had a couple of things in common with Donald Trump, an impeachment and rambling, incoherent speeches. He also gave pardons to undeserving wretches. Back in the mid-19th century, Congress took long summer vacations, and after recessing in March of 1865–before Grant’s victory and Lincoln’s death–they trotted off in their carriages to their respective states and did not return until December 4, 1865. When Johnson came into power upon Lincoln’s assassination in April, he had enjoyed the run of the place for months.

Over the summer Johnson discovered that he quite liked having dignitaries of the former Slave Power who had looked down on him in the antebellum period come groveling to him for a pardon. And indeed, former Confederates lined the road to the White House to prostrate themselves and say, “Gee, I’m sorry I wanted to start my own country in order to keep my former slaves in slavery. Did I really take up arms? I didn’t really mean it. Can we just forget that it ever happened and just go on from here?” Johnson would then grant a pardon. By the time Congress reconvened, he had pardoned some 1,500 former Confederates; by June 1866 the number reached 12,652.

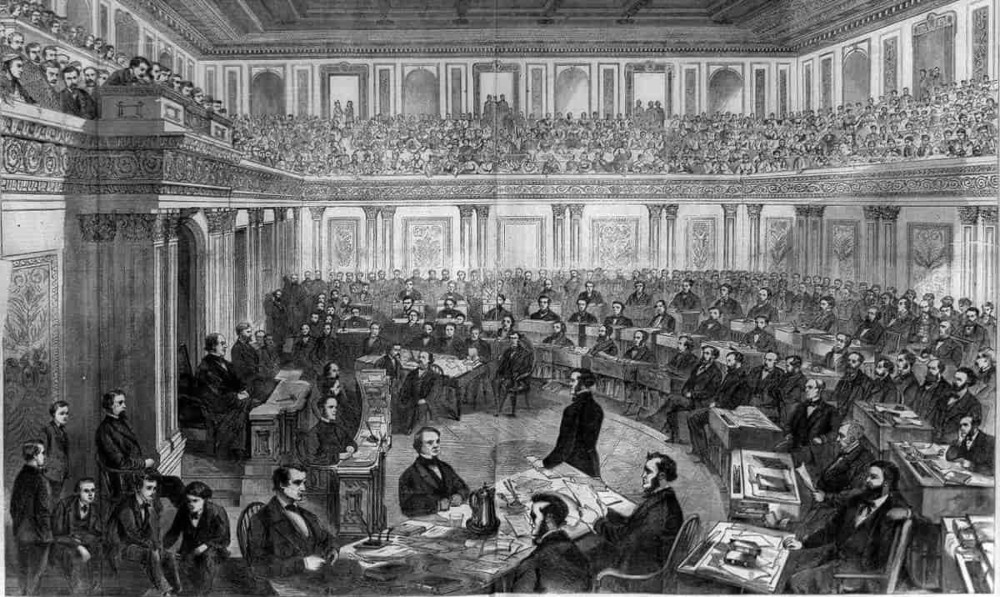

When Congress came back into session, members found themselves looking across the aisle at many of the exact people they had just beaten in a war of carnage. Amongst the members sat Confederate generals and colonels. The Republicans refused to seat them.

The ill winds of Johnson’s pardons almost swept numerous former Confederate officers back into Congress. But those winds also blew in the 14th Amendment, which re-set the rights of all Americans, including Blacks. Section One gave us birthright citizenship and the seminal equal-protection and due-process clauses that render all of us equal under the law.

But in the undergrowth of history are four other articles that are little remembered. One deals with war debt and one with Congressional apportionment and remedies for voter repression. Then there is Article 3, which reads:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath…to support the Constitution, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.

Section 5 stipulates: Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Arguably, if the Senate fails to convict Trump of the House’s impeachment charge, thereby eliminating the possibility of an immediate second simple-majority vote to disqualify him from future office, there is another path to take that would also ban Trump from holding public office ever again. It might only take a simple-majority vote in both houses of Congress to designate him as ineligible, argues renowned Civil War historian Eric Foner: “Congress can use this authority to prohibit anyone who on Jan. 6 violated an oath in this way, up to and including the president, from ever again serving in a government post, local, state, or national.”

Not surprisingly, there is ample legal debate over the amendment. David Hemel, University of Chicago Law Professor, argues that Chief Justice Salmon Chase ruled that this power to deny office lay with the courts rather than the Congress. Or could a Trump lawyer argue that this prohibition would be a “bill of attainder,” which is prohibited by Article I, Section 9, Clause 3? A bill of attainder in 1787 meant capital punishment levied by Congress without a trial, and that clause might still apply, assuming that the 14th amendment doesn’t over-ride.

This road-less-traveled is not an easy one. Still, the House and Senate could vote to disqualify Trump from holding future office with a simple majority (assuming filibustering doesn’t apply). That would put the onus on Trump to challenge their decision.

Fascinating article, a glimmer of hope amid the chaos of the current impeachment trial. Great writing, too!

Here’s a good Politico story on the legislative hurdles Congress would face if it wanted to invoke the 14th Amendment strategy to deny Trump future office. The amendment was last invoked in 1919 in this way, and there are plenty of opportunities for court challenges if the Democrats were to take this path. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/02/05/congress-still-has-one-more-way-to-ban-trump-from-future-office-466220