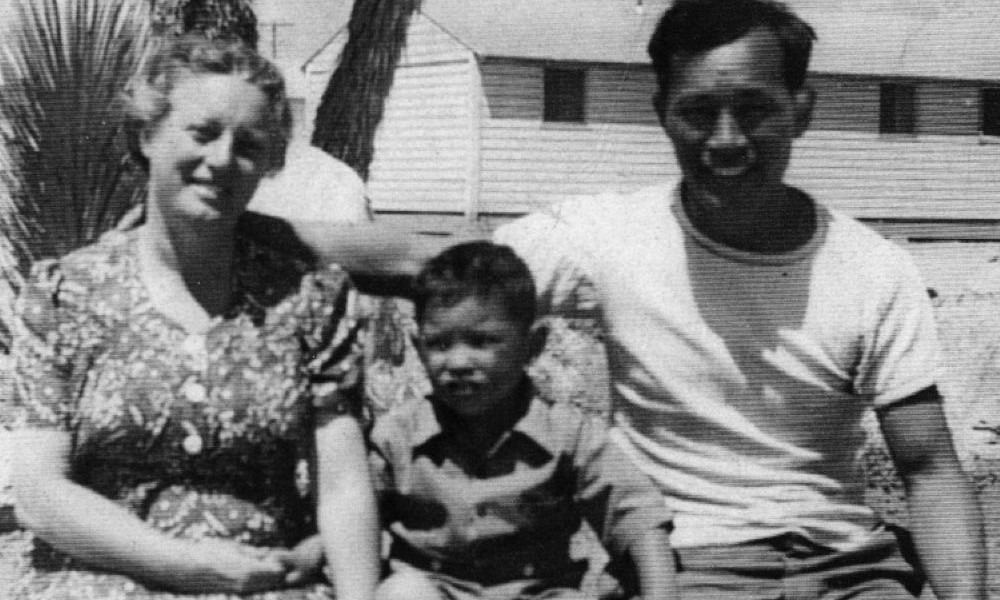

Tracy Slater’s Together in Manzanar (Chicago Review Press, 2025) tells the astonishing story of Karl and Elaine Buchman Yoneda, a biracial couple interned with their three-year-old son, Tommy, at Manzanar in the wake of Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor. (The book’s subtitle, The True Story of a Japanese Jewish Family in an American Concentration Camp, considerably undersells the book, which branches out from the Yoneda family’s internment experience to explore in depth the profound political divisions and tensions within the incarcerated community at Manzanar.)

The Yonedas were an unusual family — and not just by virtue of their racial mix; he was born in California of parents who immigrated from Japan, she in New York City to a family of Russian Jews. Both were members of the Communist Party, and both were active in the national labor movement, which at that time was very much left wing. Japanese Americans generally disapproved of them as “Reds,” and they were harassed by legal authorities as well.

Living in San Francisco when Pearl Harbor was bombed, they were immediately fearful for their wellbeing, if not their lives. The day after the bombing, Karl was summarily arrested at his work on the longshoremen’s dock and put in a crowded holding cell with other Japanese Americans. The regional Communist Party immediately expelled all Japanese American members and their spouses from the party “for the duration of the war.”

In the weeks that followed, “a string of murders targeted Japanese residents in California… Over the next month, the attacks on Issei and Nisei in California expanded to include an elderly couple killed in their bed, windows at two homes shattered with over 55 shotgun blasts, a young mother murdered, and a 19-year-old girl abducted by three Folsom prison guards posing as FBI.”

Upon his release from the immigration center holding cell, Karl and his family dared not leave their apartment. “We’re feeling increasingly hemmed in,” he wrote in his diary at the time. “It’s becoming dangerous just to go outdoors.” Barely a month after Pearl Harbor, “the Yonedas’ fellow citizens had begun publicly agitating for the incarceration of not just Japanese aliens on the West Coast but also Japanese Americans. Elaine and Karl were aghast when Congress quickly picked up the call.”

The level of racist hysteria across the nation rose ever higher. “[T]hey were dismayed by the claims of Idaho’s governor: all the Japanese in America ‘breed like rats’ and should be sent packing to Japan, or tossed into the sea.” Even political and media figures remembered now as decidedly liberal piled on. Seattle congressman Warren Magnuson enthusiastically supported the internment. And Edward R. Murrow joined the hysterical chorus with, “I think it’s probable that, if Seattle ever does get bombed, you will be able to look up and see some University of Washington sweaters on the boys doing the bombing!”

Faced with the inevitable, Karl volunteered to move to Manzanar and help to build it, in the hopes that his cooperation would allow him to enlist in the military and fight against fascist regimes in Japan and Germany. Even in the face of internment, he and Elaine were intensely patriotic, largely out of fear of a fascist takeover of the United States. His time in Japan had soured him on the Imperial government there, which he saw as equivalent to Hitler’s regime, of which he and his wife were particularly fearful, given that Elaine was Jewish.

The camp was only partially built when the first internees arrived, from Bainbridge Island. When it came time to round up California’s Japanese Americans, Elaine had to force her way into internment, as the authorities at first insisted on taking her three-year-old son, who was deemed a national security threat, without her. In an amazing display of bureaucratic doublespeak, she had to sign a document stating that “the undersigned does hereby request the privilege[!]” of accompanying her son to Manzanar.

Slater is at her best when detailing the political intrigue and violent divisions within Manzanar, and explaining the exceptional position of the Yoneda family. The camp, which came to hold 10,000 people, was populated primarily by three kinds of prisoner: Issei Japanese, who were immigrants barred from ever becoming citizens; the Nisei, who were born in this country, and thus were American citizens; and the Kibei-Nisei, Japanese-American citizens who at some point in their lives had lived in Japan.

Political divisions fell roughly (although not entirely) along generational lines. Many Issei openly rooted for Japanese victory, which they saw as leading to liberation from the camps, and some Kibei-Nisei aligned with them; most Nisei were opposed to Japanese and German fascism, and a good number of them (Yoneda included) lobbied to enlist in the armed forces for that reason, and in order to prove their loyalty to the U.S.

Yoneda’s openly patriotic stance eventually put him and his family in great danger from those far more outraged at the incarceration than he and Elaine were. Ultimately, he was allowed to enlist, and his family — and families of other enlisted men — had to be rescued from Manzanar and sent elsewhere.

There is no end to the reasons for reading this book. It is a profoundly enlightening, rigorously researched and detailed history of the internment, and a riveting story as well. Slater’s thorough accounting of the general mistreatment of the incarcerated is a remarkable achievement in itself. (Conditions in this camp were egregiously inhumane.) Her writing is particularly artful in the way it moves back and forth between the Yoneda family saga and the larger camp and national pictures.

Manzanar also offers endless chilling parallels with the present time. (Substitute “Home Depot” for “longshoremen’s dock” and “Alligator Alcatraz” for “Manzanar” — the rest of the story, along with the racist rhetoric, is practically identical.) It is worth noting that the federal government invoked the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 for the first time since 1798 in justifying the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans; the Acts were not invoked again until Donald Trump cited them in justifying his current mass roundup of immigrants.

After the internment, the Japanese phrase, “Nidoto Nai Yoni” (“Let it not happen again”) became a rallying cry against what most people hoped was an unthinkable, unrepeatable act. But reading this book, you are hit over and over again with terribly familiar statements and acts that echo today. For all of our horror at what happened in the wake of Pearl Harbor, here we are again.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.