By Bruce Ramsey

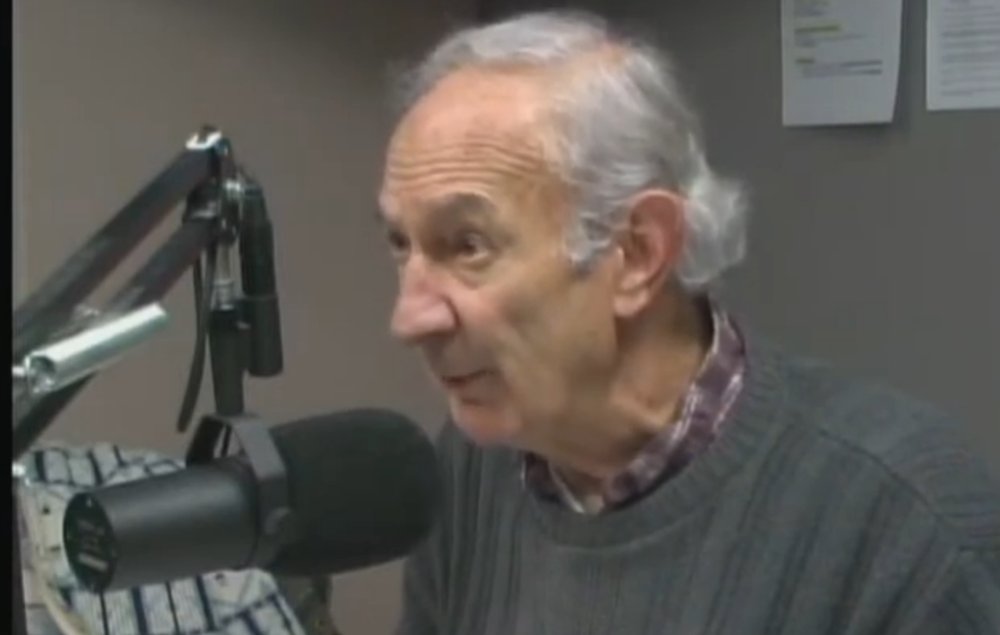

Bert Sacks came into my life 25 years ago. I was an opinion columnist on The Seattle Times editorial page. I had been arguing that George W. Bush and Dick Cheney were wrong to propose a second war against Iraq. Bert thought so too, but his viewpoint was different. Instead of looking at the power politics — Saddam Hussein did this, Bush did that, the United Nations Security Council did another thing — Bert talked about Iraqi children.

Under Saddam, Bert said, Iraq had used some of its oil money to build treatment plants for drinking water. During the First Gulf War, the United States had bombed the treatment plants. The Pentagon had done this intentionally, using smart bombs. After the war ended, the Clinton administration had prevented the plants from being repaired. The repairs required imported parts, and the sanctions blocked the imports.

The Clinton people did this to put pressure on Saddam. The sanctions hadn’t worked very well; they often don’t. What the sanctions had done over the course of the 1990s, Bert said, was to sicken millions of Iraqi children who were drinking unclean water. If you looked at Iraqi population figures, 500,000 children were missing. They had died, Bert said, of waterborne diseases. Morally, it was as if they had been killed by the government of the United States.

Bert Sacks was not the only one making that argument. It was out there, on the left, which is not where I was. I trolled the internet for counter-arguments and found none. Bert told me that Lesley Stahl of CBS’s 60 Minutes had asked Clinton’s secretary of state, Madeline Albright, about the dead children — whether the 500,000 deaths were “worth it,” and Albright had said that yes, it was worth it. It was an appalling answer, and Albright later regretted saying it, but there it was.

The Clinton people were not arguing that the 500,000 figure was a lie, and that people like Bert Sacks were making it up. It simply wasn’t what they cared about. It wasn’t one of their “talking points.” They were holders of political power, and they thought and spoke in terms of power relations.

I wrote an editorial for The Seattle Times using Bert’s argument about the 500,000 children. The editorial made Bert very happy, but he did not stop. I didn’t agree with all Bert’s views, and I didn’t always use his arguments in my writing for The Times, but I listened to him. I told Bert to think of me as his “long-term investment.” He liked that.

I also took some flak for the times I quoted him. Some people said I should stick to to more mainstream sources, safer sources, such as the voices of my own government. I thought that a number of my government’s statements were lies. Bert didn’t lie.

Newspaper people talk a lot to people who stick their necks out, and Bert stuck his neck out further than most. In 1997, he and three others carried satchels of medicine to Iraqi hospitals, where they talked to doctors treating the sick kids. His trip violated federal law. The violation wasn’t that he’d traveled there. It was that he’d engaged in forbidden commerce with the regime of Saddam Hussein by such things as paying for taxis and buying lunch.

In 2002, George W. Bush’s Justice Department hit him with a $10,000 fine for his intentional flouting of the law. Bert was living quite frugally, and I don’t know if he had $10,000, but he had plenty of friends. He could have paid it, but he refused to pay it. He invited the government to take him to court. He wanted them to take him to court, because a federal courtroom would give him a public platform for making a stink about their sanctions. In 2011, Barack Obama’s Justice Department did take Bert to court, but the judge dismissed the case and the government never did collect its $10,000.

Bert took political arguments as seriously as anyone I ever met, but he did not demonize his opponents. He was not one to accuse any person of evil. He didn’t talk about Madeline Albright that way, or Bush and Cheney, or even Saddam Hussein. He would say, “People have reasons to do what they’re doing. We need to understand what they are, even if we don’t agree with them.”

To Bert, casting out one’s opponents as evil was choosing not to understand them. It was the first step to war and the consequences of war. Also, Bert didn’t draw a distinction between the intended and the unintended consequences: If you went to war, you were responsible for both. If you supported the Iraq war, the 500,000 dead children were on you. Bert wanted to make sure you understood that.

The Disarming Activist

By Paul Andrews

When it became obvious to him that at age 83 his end was near, Bert Sacks decided to have a conversation with himself. It’s a dialogue we as a society increasingly need to pursue. “I can feel my body shutting down,” Sacks, a longtime Seattle activist who spent years drawing attention to children’s deaths and suffering in war-torn Iraq, said in late April. “I’m losing words. My thought processes are confused. I can feel myself getting weaker.”

There also was a quality-of-life issue. Wheelchair-bound, his body and mind wracked by Parkinson’s disease, Sacks felt life had increasingly less to offer. While he was still able to, he decided it was time to end it — typically, on his own rather than on society’s terms.

Consistent with his approach to any issue, Sacks spent months researching end-of-life options in Washington State. Under guidance from End of Life Washington, an advocacy group for the terminally ill, he chose a process called VSED (voluntary stopping eating and drinking). Through palliative care, Sacks received medications to ease pain and suffering.

Not wanting his decision to come as a shock to his friends and neighbors at Broadview Village Center, a North Seattle retirement community, Sacks wrote a short notice asking them not to bring food or liquids with them on visits. “I’ve not chosen this course casually,” he wrote. “I hope you will understand my reasons and think kindly of me.”

For a human-rights crusader with an unwavering sense of destiny, Sacks’ decision was a logical extension of his life’s work. Over the course of three decades, he gained international notoriety for his tireless crusade on behalf of more than 500,000 Iraqi children that UNICEF estimated were killed in the Gulf War and ensuing strife.

No one wants to see innocent children die. But where such tragedy usually evokes a shake of the head or cluck of the tongue or just a shrug at the inevitable cost of war, Sacks made it his mission to fully detail, document, and publicize the Iraq tragedy — a campaign that led him to be taken to court by the US government.

It would be an understatement to say Sacks’ path from an outdoors-loving, jack-of-all-trades to Iraqi children’s crusader was circuitous. Born March 1, 1942, Sacks grew up in the tiny Massachusetts town of Sharon, 17 miles southwest of Boston. As a youth he did well in school and got elected president of his senior high school class, but was not particularly political.

“I was born in Cambridge,” he recalled. “And my mother took me home past Harvard University, where she said, ‘I might as well submit your application now.’” True to her prophecy, Sacks was offered early admission to Harvard. But he turned it down for Dartmouth, where there was more outdoor life. “Harvard seemed too intellectual, too removed, to me, not engaged enough in the grittiness of real life,” he explained.

Even Dartmouth couldn’t hold his interest. He dropped out after two years in 1961 and undertook a variety of odd jobs — driving taxis, doing construction work, training to operate earth-moving equipment. He bounced around the country as well, doing graduate work in software programming at Stanford after getting an electrical engineering degree from Boston University. Paradoxically, given his later calling, the young Bert Sacks was an Ayn Rand disciple, rejecting altruism and the common good for radical self-interest.

An early 1970s trip to Israel, however, changed his direction. He spent months living in a kibbutz, an experience that taught him “people do better when they work together for a common purpose and goal.” Sacks married an Israeli woman and the couple moved back to the United States. The childless marriage ended in divorce in the late 1980s. From that point on, Sacks led an increasingly spartan existence, not owning a home or even a car.

Computer work took him between North Carolina and San Francisco for several years before Sacks found a job in Seattle in the early 1990s working as a software contractor. “In Seattle, Bert found his tribe,” his sister Risa Sacks observed. He got involved in peace and community gatherings in the Phinney-Greenwood neighborhood, where he became a fixture at local hangouts and the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s Western Washington office at Woodland Park Presbyterian Church.

Exactly what originally latched Sacks onto the Iraqi children’s cause is unclear. Sacks doesn’t recall any particular catalyst other than learning on a trip to Boston of an (ironically) Harvard Study Team report estimating at 170,000 the number of Iraqi children dying as a result of Gulf War sanctions. On a later trip to New York City he learned of a protest fast at the United Nations sponsored by Voices in the Wilderness, which had formed to challenge US economic sanctions against Iraq after the Gulf War.

“Bert came to one of our fasts in 1996,” recalled Kathy Kelly, a Voices leader who today is board president of World BEYOND War. “For the years immediately following he was pretty much a regular.”

Sacks had a uniquely disarming approach to activism, Kelly said. , since “he had a quiet, humble air — he was never shrill, and had an almost playful way about him.” When he’d invite friends to dinner he’d advise them to bring their own plate and fork,since “he only had one of each.” After black-garbed anarchists rioted and broke downtown store windows during Seattle’s notorious WTO protests in November, 1999, Sacks alerted media to a subsequent rally protesting Iraq sanctions where activists were going to “break windows.” Sacks brought some old framed window panes to the event to break with a hammer.

“Judges respected Bert. Doctors respected him. The Iraqis loved him” — despite Sacks being Jewish, Kelly noted. Sacks even got caught up in Rep. Jim McDermott’s “Baghdad Jim” controversy after joining the Seattle Congressman on a highly publicized trip to Iraq in 2002. McDermott unwittingly accepted $5,000 from an Iraqi-American businessman with ties to Saddam Hussein’s regime — returning the money when the contribution was questioned after an article in the Financial Times of London.

After seven trips to Iraq with toys and medical supplies for children, Sacks was fined $10,000 in 2002 for violating U.S. sanctions. He risked even worse — 12 years in jail and fines of $1 million or more. Nothing daunted him. In a classic gesture of civil disobedience, he refused to pay and was assessed another $6,000 in interest fees and penalties. The US Office of Foreign Assets Control eventually decided to sue him and the case went to court in 2011.

Sacks was delighted with the suit. He hoped his cause would come before a jury to be played out step by step in a highly publicized trial. “I needed a broader platform to get on permanent record exactly what had happened in Iraq,” he said in a soft but firm tone filled with conviction. “The best way to do that was a court case.”

As often happens with such a stratagem, however, he was foiled when the judge tossed out his case for the statute of limitations had expired. Far from celebrating, Sacks was devastated. A fine, a jail sentence — whatever it took to draw attention to his cause, Sacks felt was worth it.

Today the Iraq conflicts are a fading memory for many Americans. But wartime deaths of thousands of children in the Middle East are of course still very much in the news. On the eve of his death, Sacks lamented history’s repetition in Gaza. “Whenever the deaths of children happen, it’s mass murder,” he said. “It’s horrendous, it’s unforgivable.”

Watching Middle East horrors play out over and over through the years, Sacks became concerned Israeli militancy “would ruin the dream of them having their own country,” noted his longtime partner and caregiver, Elaine Hickman. But he resisted taking sides: “Being so close to the issue, it was never a case of black and white for him,” she said.

In the end, documentation in his court case gave Sacks some satisfaction that at least his crusade was a matter of permanent record. “It’s all there in the court records,” he said. “It’ll be there forever.”

Sacks was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2014. While the relentless degenerative disorder slowed his gait, faltered his speech, and bent his frame, it could not dent his passion for spreading the word. Year after year Sacks continued to rattle cages, writing letters to the editor, publishing blog posts, giving talks and otherwise “doing what I could to make sure the truth endured.”

Medically-assisted suicide remains controversial, and only 10 states (and the District of Columbia) permit it legally. And even where legal, options remain complicated and often impractical. Paperwork can be burdensome, and it can be difficult finding physicians willing to assist in suicide procedures. Because Parkinson’s does not qualify as a terminal disease, Sacks chose what he considered the next best alternative.

On May 16, 12 days after beginning VSED, Sacks’ life came to an end willfully and as he wished. He died with a sense of purpose and with gentle resolve — and with his own expressed brand of dignity. Sacks is survived by his sister, Risa Sacks, of Massachusetts and his longtime partner Elaine Hickman of Seattle. A memorial service will be held at 2 pm June 21 in the Seattle Mennonite Church, 3120 N.E. 125th St.

Paul Andrews is a retired Seattle Times reporter. His web page is www.PaulAndrews.com.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Two wonderful remembrances of life lived so intentionally.

I just finished reading these and was thinking along similar lines. But you put it in much better words…

His dedication to the cause that gripped him and inspired his activism is an example of how something awe-inspiring can come out of something awful. No matter what your opinion is or was of the Gulf War, his dogged opposition to its consequences qualifies him as one of its greatest heroes.

Bill’s refusal to call the warmongering politicians evil seems important. Otherwise, there will be some listeners who feel defensive. We need to convince people who support whatever party or politician to also support peace and stopping the killing of children.

Bert was a kind, erudite, and dedicated man with a gentle demeanor. His commitment to peace and justice was deep and purposeful. We should all be outraged by the rampant slaughter of children caught in the madness of war. Bert’s example is a call to resistance to the forces that precipitate the maiming and deaths of the innocent. God bless you Bert. You were a beacon of light in a world where there is so much darkness.

Thank you both for these essays. I didn’t know Mr. Sacks, but his comment resonates with me.

“People have reasons to do what they’re doing. We need to understand what they are, even if we don’t agree with them.”

He was quite a guy. I’ve had several memorable conversations with him over the years, like the time he told me he finally forgave Dick Cheney.

Once he got going on a subject and leaned forward with those big eyes boring into you – he could be pretty persuasive!

My favorite memories – him arguing with my Dad (another formidable debater, but not disciplined like Bert) about who killed JFK and best of all, when he hijacked Christmas day by popping in a VHS 9/11 truther doc and making the whole family sit around to watch it haha.